The first time I saw her cry, it wasn’t loud.

No dramatic sobs. No hand pressed to the chest like the women in penny novels. Just a quiet unraveling, as if her body had learned long ago that making noise only invited more cruelty.

It was March 15, 1857, and the light outside the big house in Greene County, Georgia had that sharp, early-spring clarity that makes every stain on a porch plank look like a confession. I was fixing the parlor shutters, my hands smelling of resin and iron, when voices rose in the sitting room like a storm crawling up the field.

“—With all due respect, Colonel Hawthorne,” a young man said, the words polished like the brass on his boots, “I cannot accept this.”

I paused, hammer hovering. I knew that tone. It was the tone of men who believed the world owed them the best cut of meat, and got offended when it was served warm instead of hot.

“What situation?” Colonel Elias Hawthorne asked, though he knew exactly. His voice was cold, the sort of cold that didn’t come from weather but from a man deciding he would rather break something than be embarrassed by it.

I slid a slat open just enough to see through the shutter’s gap.

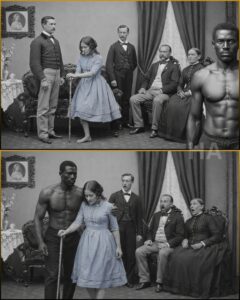

Miss Violet Hawthorne sat in the high-backed chair, wearing her best blue dress, hands trembling in her lap. A silver brooch pinned at her throat tried its hardest to make her look like a proper young lady. But the tremor gave her away. So did the cane beside her, carved from ash wood, the handle worn smooth where her fingers gripped it. I’d made that cane years ago, back when the Colonel had barked, “Build the girl something to lean on,” as if he were ordering a new fence post.

Across from her, the suitor, a planter’s son named Thomas Whitaker, stared at her like she was livestock with a limp.

“Your daughter is… defective,” Whitaker said, as if tasting the word. “How am I to present her to society? How am I to have normal children with—” His lip curled. “With a woman like that?”

The words struck her like a whip. I watched her flinch, shoulders drawing inward as if she could fold herself into the upholstery and disappear.

She tried to speak. Her mouth opened, closed. Her tongue caught.

“I… I c-can… I can l-learn,” she managed.

“Learn what?” Whitaker laughed. “To walk right? To speak like a normal person?”

Then Mrs. Lillian Hawthorne rose from her chair, slow and satisfied, like a cat stretching after a meal. She wasn’t Violet’s mother. Violet’s mother had died birthing her, which in this house was treated less like tragedy and more like proof that Violet arrived already carrying bad luck in her small fists.

Mrs. Hawthorne’s smile was thin as thread. “Thomas is correct, Elias,” she said. “The girl is a burden. Perhaps it’s time to accept reality. No man of good family will want her.”

“Good family,” Whitaker repeated, pleased to hear his cruelty dressed up as righteousness. “I’d rather die a bachelor than marry a cripple.”

Violet made a sound that wasn’t quite a sob, more like a breath being torn.

She rose with difficulty, leaning heavily on the cane, and stepped toward the door with what dignity she could gather from the floor.

“Where are you going?” Mrs. Hawthorne asked, sweet as poison.

“T-to my r-room,” Violet stammered.

“No,” her stepmother said, voice sharpening. “You will sit and hear what is decided about your future.”

The Colonel had been quiet, jaw locked, eyes fixed on some invisible point on the wall as if watching his own pride play out like theater. Now he spoke.

“Thomas,” he said, “thank you for your honesty. You may go.”

Whitaker left with the kind of bow that was really a victory lap.

When the door shut, the room fell into a heavy silence. Violet stood, trembling, tears slipping down her cheeks in clean tracks.

“Sit,” the Colonel ordered.

She obeyed. And then, as if he’d been waiting for the stage to clear, he delivered the sentence that split her life down the middle.

“Your stepmother is right,” Colonel Hawthorne said, voice flat as a shovel blade. “You are a problem that must be resolved. No decent man will marry you.”

“F-father,” Violet whispered, the word hardly audible.

“Don’t call me that,” he snapped. “A father has normal children. Not… not this.”

Violet shrank into the chair. I saw her fingers twist the edge of her skirt like she was trying to hold herself together by fabric alone.

Mrs. Hawthorne leaned closer, eyes glittering. “We must be practical,” she murmured. “And I have a solution.”

“What?”

the Colonel asked.

“Jonah,” she said.

My name—at least the one they gave me—was Jonah. Jonah Pike. Twenty-eight years old. Enslaved carpenter. Widower, if the word meant anything to people who didn’t believe our marriages counted.

My real name belonged to my mother’s mouth and died when I was sold south. The name “Jonah” was easier for this place to own.

“He is strong,” Mrs. Hawthorne continued. “A brute when he needs to be. He has no wife. He can take her off our hands. At least then she will be useful. Cooking. Cleaning. Keeping his bed warm. If God is cruel enough to let her conceive, the children will be his problem.”

My blood turned to ice. They spoke of me as if I were a mule you could lend and reclaim. They spoke of her as if she were broken furniture.

Violet lifted her head, horror widening her eyes. “N-no… please,” she said. “Don’t do this.”

“Do what?” Mrs. Hawthorne asked with false innocence. “Give you a chance to be wanted? You should thank us.”

“I d-don’t… I don’t l-love him,” Violet whispered, voice shaking.

“Love?” Mrs. Hawthorne laughed softly, the sound like a knife being sharpened. “You think you have a right to love? Be grateful anyone will take you. Even if it’s only for convenience.”

Something in me snapped, quiet but final.

I rapped the shutter with my knuckles, then pushed the parlor door open and stepped inside without invitation, hat in hand, sawdust on my sleeves.

“Excuse me, sir,” I said.

The Colonel turned sharply. “Jonah. What do you want?”

“I heard my name,” I answered carefully. “And I’d like to understand why.”

Mrs. Hawthorne’s expression soured, as if a dog had wandered into church.

The Colonel studied me for a long moment. “We have a proposal,” he said. “My daughter needs a husband. You need a wife. You will marry.”

I looked at Violet.

She stared at me through tears and humiliation, as if waiting for the next cruelty to land. In her face I didn’t see a curse or a burden. I saw a girl who had been fed contempt so long she’d begun to believe it was nourishment.

“Sir,” I said, and the words felt like stepping onto thin ice, “may I ask what Miss Violet thinks about it?”

Silence struck the room like a sudden clap of thunder. No one had asked her what she thought about anything. Not about her body. Not about her future. Not about whether she wanted to keep breathing in this house.

Violet blinked at me, stunned. “Y-you… you want to know what I think?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said, and my throat tightened around the word. “It’s your life. Your opinion matters most.”

Fresh tears gathered, but these looked different. Not only pain. Something like shock. Something like a door opening in a room she’d been locked inside.

Mrs. Hawthorne hissed, “Enough of this foolishness. The decision is made. Jonah, do you accept or not?”

I looked back to the Colonel. “I accept,” I said slowly, “but on one condition.”

The Colonel’s brow lowered. “You are in no position to make conditions.”

“I am in a position to refuse,” I said, surprising myself with the calm in my voice. “You said you have a problem that needs solving. If I am the solution, then it must be done with dignity.”

Mrs. Hawthorne scoffed. “Dignity? You are property.”

“And she has suffered enough indignity to last a lifetime,” I replied. “If she is to be my wife, she will be treated as my wife. Not as something discarded.”

The Colonel’s eyes narrowed, measuring. “What terms?”

“A home of our own,” I said. “Privacy. Respect from everyone on this plantation. And any child we have will not be treated as filth. You may call him what you like in your heart, sir, but he will not be beaten for being born.”

Mrs. Hawthorne leapt up. “Impossible!”

The Colonel lifted a hand, silencing her. He looked at Violet, who sat rigid, as if afraid to breathe wrong.

“And you, Violet?” he asked finally. “Do you accept this marriage?”

Violet’s gaze moved from me to her father to her stepmother. Her mouth trembled. Then her voice, still uneven, came out stronger than I’d heard it all afternoon.

“I… I accept,” she said. “If… if Jonah truly means what he said.”

I met her eyes and nodded once. “I do.”

The Colonel exhaled like a man who’d just chosen the lesser fire to step into. “Then it is decided. The wedding will be next week.”

When I left the big house, the sun seemed too bright for what had just happened. I walked back to my workshop, every board and nail suddenly heavier, because I had agreed to bind my life to a girl I barely knew in a world that would punish us for breathing the same air as equals.

But one thought stayed steady in me, like a nail driven deep.

Violet Hawthorne deserved kindness. If I had anything left to offer the world, it would be that.

The week before the wedding felt like living inside a held breath.

The plantation ran as it always did, crops demanding labor, overseers demanding silence, the big house demanding that everyone pretend it was a place of civilization instead of cruelty dressed in lace. But beneath that routine, a tension stretched tight.

Violet moved like a ghost in the gardens behind the big house, always alone, always with a book in her lap. Her cane tapped softly against stone paths. Sometimes I caught her looking at the fields beyond the magnolias as if the horizon itself were a story she wanted to climb into.

One afternoon, I found her on a bench beneath the pecan tree.

I took off my hat, held it to my chest the way I’d seen free men do. “Miss Violet,” I said. “May I sit?”

She looked up quickly, startled. “Y-you… you want to sit with me?”

“If you’ll allow it.”

She hesitated, then nodded. I sat at the far end of the bench, leaving distance between us. Not because I feared her, but because I knew how little control she’d had over her own space. I wanted her to feel she owned at least the air around her body.

“What are you reading?” I asked.

She held up the book. Poetry, worn at the edges. “Longfellow,” she said, the name stumbling slightly, then righting itself. “I… I like the way the words sound. Like… like they know where they’re going.”

I almost smiled. “Must be nice.”

Her eyes softened. “C-can you read?”

“A little,” I admitted. “My wife taught me. Before…” I stopped, the old ache rising like bile.

“Before?” Violet asked gently.

“Before she was sold,” I said. “And my little girl with her.”

Violet’s face tightened with empathy that looked unfamiliar on her, like she wasn’t used to being allowed to feel anything except shame.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “That… that is a grief that never sleeps.”

I stared at my hands, calloused, stained with work. “It doesn’t,” I said. “But you learn to carry it like you carry water. Careful, so you don’t spill it everywhere.”

Silence settled between us, not awkward now, but shared.

After a while, Violet asked, “J-jonah… why did you agree to marry me?”

The question was direct. It deserved honesty.

“Because I saw the way they spoke to you,” I said. “And because no one should be treated like a mistake that keeps breathing.”

She flinched as if the truth hurt even when spoken gently. “B-but I am,” she said. “A mistake. I’m… I’m crippled. I stutter. I’m—”

“Stop,” I said softly, not harsh, just firm. “You’re a person. And you’re smart. I’ve seen you with those books. I’ve seen you slip bread to the kitchen girl when no one is watching. I’ve seen you mend a bird’s wing with a strip of cloth.”

Her eyes widened. “Y-you noticed?”

“I notice,” I said. “It’s what you do when you’re trying to survive.”

Violet swallowed, throat working. “No one has ever… ever said good things about me.”

“Then it’s time someone started,” I replied.

Her lips trembled into something almost like a smile, startled by its own existence.

That afternoon didn’t make us lovers. It didn’t erase the horror of how this marriage had been arranged. But it planted something small and stubborn between us: the beginning of trust.

The wedding took place on a rainy Thursday, gray sky pressed low over the chapel like a hand trying to keep everything quiet.

A preacher muttered words over us while the Colonel stood stiff in his fine coat and Mrs. Hawthorne watched with a satisfaction she didn’t bother to hide. A handful of enslaved people stood as witnesses, faces carefully blank. We all knew what happened to those who showed too much feeling.

Violet wore a plain white dress. It didn’t hide her limp. It didn’t need to. For the first time, she held her chin slightly higher, as if she was testing whether dignity could be worn like fabric.

When it came time for vows, her hands shook so hard I could see the tremor travel up her wrists.

“I… I promise,” she whispered, “to t-try… to be a good wife.”

It wasn’t romantic. It was raw, human, honest.

“I promise,” I said, meeting her gaze, “to be a good husband. To honor you. To keep you safe as far as any man can.”

After, the Colonel led us not into the big house but to a small cabin at the edge of the property. It was simple: two rooms, a hearth, a table scarred with old use. But it was ours. Or as close to ours as anything could be in a world built on ownership.

When the Colonel left, the cabin filled with the awkwardness of strangers who had been forced into a sacred promise.

“You must be tired,” I said at last. “You can take the bed. I’ll sleep by the fire.”

Violet blinked. “B-but… we are married.”

“We are,” I said. “But you don’t owe me your body because men decided something in a parlor. We can wait until you feel… safe.”

Her eyes flooded again, but this time the tears slid down quietly, like rain on window glass.

“You are… kind,” she whispered, as if the word tasted strange.

“Then get used to it,” I said, more gently than the words sounded. “Because I mean to be.”

In the weeks that followed, routine stitched us together.

I worked during the day. Violet kept the cabin, cooked meals that improved with practice, and, in the evenings, sat by the fire with her book while I repaired tools. We talked in small pieces at first. Then longer. Then like two people who had been lonely in different ways and suddenly found a voice answering back.

I learned that Violet had taught herself to read by stealing moments in the big house library, tracing words with her finger like a blind person learning a face.

“I wanted to go places,” she confessed one night, staring into the flames. “So I went in books. It was safer than going in my body.”

“You go anywhere you want with me,” I said, surprising both of us.

She looked at me as if trying to decide whether hope was a trick. “Do you… do you really mean that?”

“I do.”

Over time, her stutter eased when she wasn’t afraid. Not gone, but softened. Like a river that had been forced through stones finally finding a wider path.

And something changed in me, too.

For three years I had lived hollowed out by loss, my wife and child sold away as if love were a luxury reserved for the free. Violet didn’t replace them. Nothing could. But she gave my grief a place to rest. She looked at me like I was a man, not an instrument. And in that gaze, a part of me that had been buried began to breathe.

By May, affection had turned into something warmer, something that made me look forward to the sound of her cane tapping the floor as she came to the door when I returned.

One night, she stood in the doorway of the room.

“J-jonah,” she said, voice soft. “May I… may I sleep in here tonight?”

I sat up, heart thudding. “Are you sure?”

She nodded, cheeks flushed, eyes steady. “I want to be… your wife. Not because I owe it. Because I… I choose it.”

The word choose landed like a prayer.

That night, we moved carefully, respectfully, as if handling something fragile that could break if rushed. Violet trembled at first, then relaxed when she realized tenderness was real. When she lay against my chest afterward, she whispered, “Thank you.”

“For what?”

“For making me feel… wanted,” she said. “Like a woman. Not a burden.”

I held her and stared at the dark ceiling, thinking how strange it was that the world could call someone broken and yet she had just healed a piece of me.

In August, Violet told me she was pregnant.

She said it in the morning, hands shaking, eyes shining.

“I… I think there is a baby,” she whispered, one palm pressed to her belly as if already guarding him.

My breath caught. Joy surged so fast it frightened me, like laughter in a place you’ve only ever whispered.

“A baby,” I repeated.

She nodded, tears spilling. “O-ours.”

I lifted her carefully, spun once, and we both laughed and cried like foolish, grateful children.

For a few days, we lived inside that joy, making plans we had no right to make in this world. Names. Stories. How we might teach a child to read by candlelight. How we might keep him safe from a system designed to devour him.

Then the Colonel found out.

He summoned us to the big house, where Mrs. Hawthorne sat like a judge who’d been waiting years to pass sentence.

“A slave’s child,” the Colonel snarled, staring at Violet’s belly as if it were an insult. “A mongrel bastard in my bloodline.”

“It is your grandchild,” Violet whispered, voice cracking.

“It is nothing,” he barked. And then, with a sudden quiet that was worse than shouting, he turned to me. “Jonah. You will be sold.”

My chest tightened. “Sold?”

“To a plantation in Mississippi,” he said. “Arrangements are made. You’ll be taken Friday.”

Violet cried out. “No! You cannot!”

“I can,” he replied. “And I will. I will not have my daughter birthing slave children on my land.”

Mrs. Hawthorne leaned in, voice silky. “It solves everything.”

That night, Violet clung to me in our cabin, shaking as if the wind itself had teeth.

“We have to run,” I said finally, the decision rising up from somewhere deep and desperate.

“R-run?” she whispered. “Where?”

I thought of stories whispered at night in the quarters. Of maroon communities hidden in swamps and forests. Of people who had made freedom with their own hands in places the law refused to look.

“There’s a settlement in the Okefenokee,” I said. “Deep swamp. Folks who won’t be found unless they want to be. We can go there. Raise our child where no one owns him.”

Violet stared at me. Fear and hope wrestled across her face.

“If they catch us…” she began.

“Then we die trying,” I said, voice low. “But I won’t live kneeling while they tear us apart.”

She swallowed hard. Then she nodded once, fierce and trembling. “Then we go,” she said. “Together.”

We left at noon two days later, when the fields were quiet and the overseers were eating, fat with their own certainty.

Violet walked with her cane, a small bundle on her back. I carried food, tools, a blanket. We moved through the orchard, then along the creek, using water to mask our tracks where we could. Every snapped twig made my heart jump. Every distant shout turned my blood cold.

“Does it hurt?” I asked when Violet’s limp worsened.

“A little,” she breathed. “But I can… I can do this.”

I wanted to carry her, but she refused at first, jaw clenched. “Let me walk,” she insisted. “I have been carried by shame my whole life. Let me carry myself.”

By dusk, we crossed the property line, stepping into woods that didn’t belong to the Colonel, didn’t belong to any man we could see. Violet stopped, staring at the trees like they were a church.

“We did it,” she whispered. “We… we are outside.”

“Outside,” I echoed, and the word felt like a door unbolting.

We slept that night in a hollow between roots, wrapped in a blanket damp with dew. Violet pressed her hand to her belly and smiled at the darkness.

“Our baby will be born free,” she whispered.

I kissed her forehead. “Yes,” I promised, though promises were dangerous things in this world.

For months, we lived hidden, moving with the seasons and the kindness of those who understood what it meant to run. We found the maroon camp deep in the swamp: a scatter of cabins on raised stilts, gardens grown in patches of stubborn sunlight, children laughing softly because even their joy had learned caution.

There, Violet became herself.

No longer the Colonel’s secret shame. No longer a girl examined like cattle. She taught children to read beneath a canopy of Spanish moss, her voice steadier when she spoke words that belonged to everyone. Her limp was not mocked. It was simply part of her, like the curve of a river.

I built furniture, repaired roofs, carved toys. For the first time, my hands made things for a community that called me brother, not property.

Some nights, Violet and I lay outside and watched stars float like lanterns above the swamp.

“I am happy,” she told me once, voice amazed. “Do you know that? Truly happy.”

“I know,” I said. “I can hear it in your laugh.”

She laughed then, soft and bright. “I didn’t know I had one,” she admitted.

And I realized something painful and beautiful: love had not just been a feeling between us. It had been an act of rebellion. A way of declaring we were human in a world invested in denying it.

In December of 1859, when Violet was eight months pregnant, the hunters found us.

They came at dawn, when fog lay thick over the swamp like a shroud. Shouts cracked through the trees. Gunshots echoed, birds exploding into the air.

“Riders!” someone screamed. “Slave catchers!”

Chaos erupted. People scattered into hidden paths. Fires were kicked out. Children were grabbed. The swamp, which had held us like a secret, suddenly became a labyrinth under siege.

I yanked Violet upright. “We have to move.”

She tried, but her leg faltered under the weight of her belly. Panic flashed across her face.

“I can’t run,” she whispered.

I scooped her up without asking this time. “Then I’ll carry you.”

She clutched my neck. “Jonah—”

“No arguing,” I said. “Not now.”

We reached a narrow path between cypress roots when a voice barked behind us.

“Stop!”

Five men emerged, rifles raised. Their leader had a scar down his cheek and eyes like stones. He grinned as if he’d been waiting for this moment.

“Well,” he drawled, “if it isn’t Colonel Hawthorne’s little cripple and her runaway husband.”

Violet’s body went rigid in my arms.

“How did you find us?” I demanded, stepping back, searching for any opening.

“Money,” the man said. “The Colonel put a fine bounty on you. Especially after he heard about the baby.”

His gaze slid to Violet’s belly with a disgusting interest. “He wants what’s his.”

Violet lifted her chin, trembling but fierce. “I am not his,” she said. “And neither is my child.”

The man laughed. “That’s a sweet story. But stories don’t change chains.”

They took us.

The journey back was three days of torment. My wrists were tied, a rope looped cruelly around my neck like I was an animal led to slaughter. Violet rode a mule, each jolt drawing a hiss from her lips. On the second night, her pain sharpened into something worse.

“Jonah,” she whispered, face slick with sweat, “the baby… I think he’s coming.”

The leader cursed. “Not here.”

“She needs help,” I said, voice breaking. “You don’t understand. She’ll die.”

He hesitated, then snapped his fingers. “Untie him,” he ordered. “But if you try anything, I’ll put a bullet in both of you.”

My hands were freed. I knelt beside Violet as she lay on a blanket in the dirt, moonlight turning her face pale.

“I’m scared,” she sobbed.

“I know,” I murmured, gripping her hand. “Look at me. You’re stronger than you think. You walked out of that house. You crossed a swamp. You built a life with your own hands. You can do this.”

Tears spilled down her cheeks. “Our baby… he will be born in chains.”

“No,” I said fiercely, even as I felt the lie crack. “He will be born loved. That is a kind of freedom no one can steal.”

Labor took the night. Violet fought with a courage that made my heart ache. At dawn, a baby boy arrived, screaming into the world with full lungs and fury, as if outraged by the injustice of his first breath.

“It’s a boy,” I whispered, shaking. I placed him against Violet’s chest.

She smiled, exhausted and radiant. “My… my son,” she breathed. “Our—our son.”

“What name?” I asked, voice rough.

She blinked slowly, then whispered, “Caleb.”

I kissed her forehead. “Caleb,” I repeated. “Hello, son.”

But joy was brief, like sunlight through storm clouds.

Violet’s bleeding didn’t stop. Her skin went gray, lips paling. Panic rose in my throat like fire.

“Violet,” I begged, “stay with me. Please.”

She looked at me, eyes shining with love and something like peace.

“Jonah,” she whispered, “promise me.”

“Anything.”

“Promise… you will tell him… that I chose this,” she said, breath thin. “I chose love. I chose… freedom.”

“You’ll tell him yourself,” I sobbed.

She smiled faintly. “Promise.”

“I promise,” I choked.

She reached out, touched Caleb’s cheek with trembling fingers, then looked back at me.

“I… I am not… a burden,” she whispered.

“No,” I said, voice breaking. “You never were.”

Her eyes closed. Her hand slipped from mine. And the world, which had been cruel enough already, somehow found room to be crueler.

When we reached Hawthorne Plantation, the Colonel stood at the gate, face carved from anger and fear.

“Where is my daughter?” he demanded.

I stepped forward with Caleb wrapped against my chest, my shirt soaked with the baby’s warmth. “She died,” I said. The words felt like swallowing glass. “She died bringing your grandson into the world.”

The Colonel’s expression flickered, something cracking beneath the hard surface. Then it froze again into fury.

“She died because of you,” he spat.

“She died because she was never allowed to live here,” I said, the grief turning sharp. “You hid her like shame. You broke her with words. Out there, in the swamp, she learned joy. She died after tasting what you denied her.”

His gaze dropped to the baby. For a moment, he looked like a man seeing a ghost.

“That child is mine,” he said hoarsely. “Give him to me.”

I tightened my hold. “No.”

“You are a slave,” he roared. “You have no rights.”

“I have a promise,” I said. “And I will keep it.”

For a long moment, the Colonel stared at me, then at the baby. Something in his face shifted, like pride meeting its own ruin.

He didn’t order the baby taken.

Instead, he did something that stunned everyone, including himself.

He said, quietly, “Put Jonah in the cellar. Bring milk for the child.”

For three days, I stayed in a damp, dark room beneath the big house, rocking Caleb in my arms, feeding him goat’s milk smuggled by an older enslaved woman whose eyes held a lifetime of unspoken prayers.

On the third night, the cellar door opened. The Colonel came down alone. No wife. No overseer. Just a man and his ghosts.

He looked older than I remembered, shoulders sagging as if the weight of his choices had finally landed.

“Jonah,” he said, voice low. “We need to talk.”

“About what?” I rasped.

“About the boy,” he said. “And about… her.”

I didn’t answer. My silence was a wall.

The Colonel sat on a crate, hands clasped, staring at Caleb’s sleeping face.

“He has her eyes,” he whispered.

“Yes,” I said. “And if he grows up here, he’ll learn what those eyes learned. That love is conditional. That kindness is a rare event.”

The Colonel flinched.

“I was wrong,” he said, the words scraped raw. “I was afraid. Afraid of what people would say. Afraid of being mocked. And I turned that fear into… into cruelty.”

I didn’t soften. Not yet. “Fear doesn’t excuse it,” I said.

“No,” he admitted. “It doesn’t.”

He swallowed hard. “I cannot bring her back,” he said. “But perhaps I can do one thing that matters.”

He lifted his gaze to me. “I will free you.”

My breath caught. “What?”

“I will write your papers,” he said, voice steady now, as if deciding this was the only way to keep breathing. “And the boy will be raised as my grandson. He will be educated. Protected. Not sold. Not beaten. Not treated as a stain.”

“And Mrs. Hawthorne?” I asked.

The Colonel’s jaw tightened. “She will learn that my grief has teeth.”

I stared at him, searching for trickery. But what I saw was something worse than manipulation.

Regret.

It sat in his eyes like a sickness.

I thought of Violet’s last whisper. I am not a burden. I thought of the promise in my throat.

“I accept,” I said finally. “But on conditions.”

He nodded once, like a man who understood he had forfeited the right to be offended.

“Caleb will know who his mother was,” I said. “He will know she was brave. That she chose love over fear.”

The Colonel’s eyes glistened. “Agreed.”

“And I will visit her grave,” I said. “Regularly.”

“Agreed,” he whispered.

I hesitated, then added the last condition, the one that felt like building a bridge over a canyon.

“You will look at your grandson,” I said, “and you will try, every day, not to see your shame. You will see… her.”

The Colonel closed his eyes, as if the words stabbed and healed at the same time.

“I will try,” he said.

Years passed like the slow turning of a page.

I remained on the plantation, not as property but as a paid carpenter, and as Caleb’s father in every way that mattered. The Colonel kept his word, even when society muttered. He pushed Mrs. Hawthorne out of power, and her bitterness curdled into silence.

Caleb grew strong, bright-eyed, quick with questions. By five, he could read better than most grown men on that land. He followed me into the workshop, watching the way I measured boards.

“Papa Jonah,” he asked one day, “why do we make things?”

“Because making is a kind of freedom,” I told him. “You take something rough and turn it into what you choose.”

He considered that, brow furrowed. “Did Mama… make herself free?”

My throat tightened, but I nodded. “Yes,” I said. “She did.”

The Colonel, for all his effort, never truly recovered. Guilt hollowed him. He drank. Some nights I heard him pacing the big house, murmuring into dark corners as if Violet might answer if he begged loud enough.

One night, he stumbled to the porch where I sat, whittling a small toy for Caleb.

“Do you think she could forgive me?” he asked, voice thick.

I looked out at the moonlit fields, remembering Violet’s laugh in the swamp.

“She had a gentle heart,” I said. “She forgave people who didn’t deserve it.”

He exhaled, shaking. “I called her a burden,” he whispered. “And she died… before I ever truly saw her.”

“You see her now,” I said. “In the boy.”

The Colonel’s eyes filled, and he turned away, ashamed of his own tears.

When the Civil War came, it tore the South apart like cloth under strain. The plantation system that had fed men like Colonel Hawthorne their sense of power began to collapse beneath fire and law and blood.

When emancipation finally became reality, the land changed. Slowly. Bitterly. But it changed.

By then, the Colonel was dead, taken by illness and the relentless poison of his own regret. His will left land to Caleb, and money to build a school. Mrs. Hawthorne fought it in court and lost, her outrage unable to outrun a signed name and a witness.

Caleb grew into a young man with his mother’s eyes and his father’s stubborn mercy.

“I want to study medicine,” he told me at sixteen, returning from a small school in Atlanta where he had endured insults and threats and still brought home books.

“Why medicine?” I asked, though I already knew.

He looked at me, serious. “Because Mama died without help,” he said. “Because people treated her body like a curse. Because I want to heal what the world calls broken.”

My chest filled with something fierce and proud. “Then you will,” I said. “And you will carry her story with you like a lantern.”

He did.

Years later, when Caleb opened a small clinic that treated Black families, disabled veterans, poor white farmers, anyone who came with pain and no money, he placed a framed quote on the wall. Not a Bible verse. Not a law. A sentence written in careful script.

Being different is not being lesser.

He told people it was his mother’s truth.

And on quiet Sundays, Caleb and I walked to the small hill where Violet lay, beneath a simple marker.

He would kneel, set wildflowers down, and whisper, “I am living, Mama. I am free.”

I would stand behind him, old hands folded, and feel the promise I made in the dirt of a cold night finally settle into something like peace.

Violet’s life had been short, but it was not small.

It bent the shape of a plantation. It cracked open a man’s pride. It raised a child who became a healer. It proved, in a world obsessed with ownership, that love could still choose.

And every time Caleb smiled at a frightened patient and said, “You matter,” I heard Violet’s voice, clear at last, whispering back through the years:

I am not a burden.

THE END

News

Billionaire Invited the Black Maid As a Joke, But She Showed Up and Shocked Everyone

The Hawthorne Estate sat above Beverly Hills like it had been built to stare down the city, all glass and…

Wife Fakes Her Own Death To Catch Cheating Husband:The Real Shock Comes When She Returns As His Boss

Chicago could make anything feel normal if you let it. It could make a skyline look like a promise, make…

Black Pregnant Maid Rejects $10,000 from Billionaire Mother ~ Showed up in a Ferrari with Triplets

The Hartwell house in Greenwich, Connecticut did not feel like a home. It felt like a museum that had learned…

Single dad was having tea alone—until triplet girls whispered: “Pretend you’re our father”

Ethan Sullivan didn’t mean to look like a man who’d been left behind. But grief had a way of dressing…

“You Got Fat!” Her Ex Mocked Her, Unaware She Was Pregnant With the Mafia Boss’s Son

The latte in Amanda Wells’s hands had been dead for at least an hour, but she kept her fingers curled…

disabled millionaire was humiliated on a blind date… and the waitress made a gesture that changed

Rain didn’t fall in Boston so much as it insisted, tapping its knuckles against glass and stone like a creditor…

End of content

No more pages to load