They said the old man’s silence was more dangerous than a loaded gun, because a gun only hurt the person it was pointed at, while his silence made an entire room point itself inward. Vincent Marlowe had built a dynasty on steel, real estate, and fear, and now, at eighty-one, he carried his reputation the way other men carried a cane: not because he needed it, but because everyone else did. On winter nights in Manhattan, when his name drifted through a restaurant like cigar smoke, the air seemed to thicken, and even powerful people learned the oldest rule of survival, the one that required no money at all: don’t be seen.

The rule lived at Aurelia, the exclusive restaurant tucked along 56th Street where the lighting was so low it made millionaires look like rumors. The guests came here to be swallowed by velvet and discretion, and the staff were trained to move like shadows, to pour and vanish, to smile with their mouths and not their eyes. Elena Rizzi, twenty-three, stood with the other servers at the kitchen pass while the maître d’, a sharp-featured man named Luc Duval, inspected them the way a general inspected soldiers before a battle he didn’t intend to survive. Elena kept her chin up as if pride could stitch new leather into her shoes, though the soles had thinned so much she could feel the marble floor’s cold through them, a reminder with every step that rent was due and mercy was not.

“Table One arrives in five minutes,” Luc hissed into the headset he wore like a crown. His gaze swept the line, pausing on Elena as if he’d already decided she was the weak link. “Listen carefully. You do not speak unless spoken to. You do not offer suggestions. You do not ask if everything is to their liking. You pour, you place, you vanish. Understood?”

“Yes, chef,” the staff murmured, even though Luc wasn’t a chef and everyone knew it. He liked the word because it sounded like authority, and in Aurelia, authority was served before the appetizers.

Elena swallowed hard. Table One was the Marlowe table. Everyone in Manhattan knew the Marlowes the way sailors knew storms. The son, Julian Marlowe, thirty-two, was a tech billionaire who had turned his father’s old-world industry into sleek new-world gold, and he wore that evolution like a tailored suit. He was handsome in the expensive, icy way of men who looked like they’d never been told no, and he had a reputation for firing people for breathing wrong. But it wasn’t Julian who made the staff’s hands sweat on polished glassware; it was Vincent.

Rumors clung to Vincent Marlowe like dust in a sunbeam. People said he hadn’t spoken a kind word since his wife died twenty years ago. People said he once bought a luxury hotel just to fire the valet who scratched his car. People said he could look at you for three seconds and calculate your entire life as either useful or disposable. Elena tried to tell herself it was all exaggeration, that men became myths when money needed a costume, but she had also seen enough in her short life to know that cruelty didn’t require imagination.

Luc snapped his fingers near her face. “Elena. You’re on water and bread service for Table One. Don’t make me regret it.”

“I won’t,” she said, keeping her voice steady even as her stomach tightened. She needed this job. Her mother needed dialysis back in Ohio. Her mother’s hospital bills came in envelopes like threats, piling up in Elena’s tiny Queens apartment until the apartment itself felt smaller, as if debt took up physical space.

“I don’t care about you,” Luc replied, smoothing his cuffs. “I care about my bonus. Now go.”

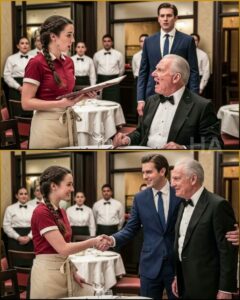

The double doors at the front of Aurelia opened, and the restaurant’s mood shifted as if a hand had turned down the volume on the world. First came the security detail, scanning the room with eyes that missed nothing, and then Julian Marlowe entered, already speaking into an earpiece, his suit a deep navy that made him look like the night sky had been tailored for him. Finally Vincent arrived in a wheelchair pushed by a stone-faced nurse, and the room did something Elena had never seen in a restaurant: it held its breath.

Vincent wore a tuxedo that looked like it belonged to another century, severe and immaculate, and his face was a map of deep lines that told stories no one dared to ask about. His eyes, dark and watery, stared straight ahead at nothing, as if he’d conquered the world and found the view disappointing. People pretended not to look, which meant everyone looked anyway, each glance quick and terrified, like children checking a closet.

Elena hurried to the side station and lifted the heavy crystal pitcher. “Just pour and vanish,” she told herself, repeating it like a prayer. “Just water, bread, and invisibility.” She approached the velvet-roped corner where the Marlowes sat, feeling the invisible wall around their table, the boundary that said human rules didn’t apply here.

As she poured, the water cascaded in a clean, silent stream into Vincent’s goblet. The old man’s hand twitched on the armrest, and Elena’s body went rigid, as if the twitch had struck her. Vincent didn’t look at her, but his voice scraped the air like gravel. “The water is too cold.”

Elena froze, the ice clinking softly like tiny bones. Julian sighed with the weary impatience of someone used to bending reality. “Father,” he said, rubbing his temples, “it’s water. Drink it.”

“It hurts my teeth,” Vincent replied, his voice dropping lower, and Elena recognized the tone even without understanding it fully. It wasn’t a complaint. It was a warning. “They bring me ice when I have old bones. No one thinks. Incompetence.”

Luc was already rushing over, pale, apologizing so hard his words practically bowed. “My deepest apologies, Mr. Marlowe. We’ll replace it immediately. Elena, move.” He shoved her aside, not gently, and Elena stumbled, fighting to keep the pitcher upright. Her cheeks burned, not only from humiliation but from the familiar, bitter realization that she could be invisible and still blamed.

She retreated to the service shadows, and from there she watched the Marlowe table like someone watching a play from backstage. Julian was all clipped movements and quiet fury, eating with aggressive precision as if he could cut his way through the evening. Vincent sat like a statue in a chair that moved, his gaze drifting as though he was somewhere else entirely. Luxury surrounded him, but it looked like a prison, and Elena felt a strange ache in her chest that wasn’t pity so much as recognition.

By nine o’clock the tension at Table One was thick enough to choke on. Courses arrived and returned untouched, which made the kitchen boil over with panic. Chef Matteo, a genius with a temper, slammed spoons, cursed in Italian and English, and sent assistants scurrying like frightened birds. “He insults me!” Matteo shouted. “This is the finest menu in New York. Does he want a hot dog? Is that what he wants?”

Elena stood at the pickup window waiting for a bread basket refill, and before she could stop herself, she murmured, “Maybe he’s not hungry.”

Matteo’s eyes snapped to her. “You don’t speak about guests,” he barked. “Take the bread. Go.”

Back in the dining room, Julian’s anger tightened into something sharper. “You have to eat something, Dad,” he said, not looking up. “The nurse says your weight is down again.”

“The food tastes like metal,” Vincent grumbled, picking at the tablecloth thread with a gnarled finger, unraveling it slowly as if he enjoyed watching something fall apart. “It has no soul. Plastic food for plastic people.”

“This is a three-Michelin-star restaurant,” Julian hissed. “Stop being difficult just to punish me.”

Vincent finally looked at his son, and Elena saw the shock in that gaze: sharp, lucid disappointment that had nothing to do with age. “I don’t need to punish you,” Vincent said quietly. “You punish yourself enough with your greed.”

Julian’s fork clattered loud enough to turn heads. The nurse looked away. Vincent didn’t raise his voice; he didn’t have to. He slumped slightly, as if the effort of speaking had drained him, and for a heartbeat he looked less like a titan and more like a man who wanted to go home but couldn’t remember where home was anymore.

Elena approached with the bread basket, an artisan sourdough served with cultured butter. She placed it down, ready to vanish, but Vincent reached out and touched the crust, not taking a piece, just feeling the texture like someone reading Braille. His fingers trembled.

“Too hard,” he whispered, and something in his tone cracked open the air. “Everything is too hard.”

Elena paused. She was supposed to walk away. Luc watched from the podium like a hawk. But Vincent’s voice wasn’t the voice of a cranky billionaire anymore; it carried the cadence of a man thinking in another language, a man translating his loneliness into English because no one around him spoke anything else. Elena’s mind flickered to her own grandfather, Nonno Pietro, who had been a carpenter in Ohio and who, when dementia began chewing through his memories, stopped eating hospital food because it “tasted like paper.” He’d wanted things that made him remember he was alive, not simply being kept alive.

Elena looked at Vincent’s hands, calloused despite the decades of wealth, hands that belonged to someone who had worked for everything and still remembered the feel of it. A tabloid article she’d once read resurfaced: Vincent Marlowe, born Vincenzo Mazzaro, came to America in the fifties with nothing but a suitcase, worked in mills, bought mills, became myth. Elena stared at the untouched foie gras and the fancy foam, and she understood suddenly that Vincent wasn’t being difficult. He was starving for a memory.

She shouldn’t do it. She needed this job. She needed tips. Her phone had been vibrating all week with collection calls, and she’d been letting them go to voicemail because listening made her feel like she was drowning. But looking at Vincent’s eyes, she felt her heart do something it almost never allowed itself to do in New York: it softened.

Elena stepped closer, breaking the invisible barrier. Julian looked up, annoyed, already ready to crush whatever mistake she was about to make. “What is it?” he said. “We didn’t ask for anything.”

Elena ignored him. She leaned down until her face was level with Vincent’s, and the room seemed to stop. Luc began speed-walking toward the table, panic widening his eyes. Elena took one breath, and in it she fit every reason she should be quiet, every fear that kept her polite, every bill waiting at home. Then she whispered a single Italian word, soft as confession.

“Scarpetta.”

Vincent’s head snapped up like a door thrown open in a storm. For the first time all night, his gaze focused completely. He looked at Elena, really looked, as if the word had turned on a light. “What did you say?” he rasped.

Luc arrived, breathless, reaching for Elena’s arm. “Mr. Marlowe, I am so sorry. This waitress is new. She’s leaving immediately—”

Vincent raised a hand. “Stop.”

The command cut the air clean. Luc froze, his fingers hovering inches from Elena’s elbow. Julian stared, confused by his father’s sudden attention, as if a statue had spoken.

Vincent’s eyes searched Elena’s face with something that wasn’t anger. It was hunger. “Say it again,” he said.

Elena’s knees trembled, but she held herself upright with a stubbornness she’d inherited from a family of immigrants and factory workers. She smiled, small and sad. “Fare la scarpetta,” she whispered, and she didn’t just translate words, she translated a world. “It means… making the little shoe. Using bread to wipe up the last of the sauce.”

Vincent’s mouth opened slightly. The harsh mask of the billionaire cracked, and beneath it Elena saw a boy who had once been poor enough to treat sauce like treasure. “My mother,” Vincent whispered. His voice shook. “She used to say—”

“If you don’t do the scarpetta, the cook will cry,” Elena finished softly, quoting the proverb her grandfather used to say. “Because the sauce is the soul.”

Vincent’s eyes filled with tears, real tears, and the entire restaurant seemed to tilt around that fact. Julian looked between them, stunned, as if he’d just watched his father become human in public. “What is happening?” Julian demanded. “What did she say to you?”

Vincent ignored him, pointing with a trembling finger at the untouched pasta dish on the table. “This is not food,” he said, his voice rising for the first time. “This is art. I cannot eat art.” He turned to Elena. “Do they have sugo? Real sugo?”

Elena knew the menu. There was no plain tomato sauce, only reductions and foams. She could feel Luc’s horror like heat behind her. But Vincent’s eyes weren’t asking for a menu item; they were asking for home.

“I can ask the kitchen,” she said, then glanced toward Luc as if daring him to stop her. “Actually… I know what you need.” She turned her head toward the pass, toward the chaos where Matteo was likely ready to murder someone. “Chef Matteo has staff sauce,” she said, voice steady now. “The real one. Garlic, tomato, basil. You want that.”

Luc hissed, “Are you insane?”

Vincent slammed his hand on the table. The sound echoed off mahogany. “Do as she says,” he roared. “And bring me soft bread. Not this rock.”

For ten minutes the restaurant existed in suspended animation. Diners pretended to focus on their own meals, but their attention was a magnet pulled toward the Marlowe table, toward the moment power flickered. When Luc returned, his face drained of color, he carried a simple white bowl of spaghetti coated in bright red sauce, the kind made for hungry staff before service, not for wealthy guests who wanted to taste technique instead of comfort. The smell was immediate, basil and garlic and something older than Manhattan: the scent of someone’s kitchen on a weekday.

Vincent didn’t wait for silverware protocols. He twirled a bite, shoved it into his mouth, sauce smearing his chin, and he did not care. He chewed, closed his eyes, swallowed like a man drinking water after years in a desert. Then he took the soft roll Elena placed beside the bowl and wiped it clean, scarpetta, mopping up every last streak of red until the bowl looked licked by devotion.

Julian watched as if he didn’t recognize the man in front of him. “Adrien,” Vincent said suddenly, then corrected himself, as if the past and present had tangled. “Julian. Taste it.”

Julian blinked, stiff with pride. “I’m fine, Dad.”

Vincent’s gaze sharpened. “You will taste it.”

Elena saw Julian’s world shift in tiny, reluctant steps. He looked at the cheap pasta, then at his father’s stained napkin, then at Elena, the waitress who had just committed social treason. He didn’t take a bite, but he didn’t argue either, which in a man like Julian counted as a crack in armor.

Vincent wiped his mouth and looked at Elena with a weight in his eyes that made her uneasy. “What is your name?” he asked.

“Elena,” she replied. “Elena Rizzi.”

He repeated it softly, as if tasting it. “Elena Rizzi. You are the first person in five years who looked at me and saw a man, not a bank account.” He reached into his tuxedo pocket. Julian tensed, thinking it was money, thinking everything ended in a transaction. But Vincent pulled out a battered leather notebook, scribbled something with a gold pen, tore out the page, and handed it to Elena.

“If you ever get tired of carrying water for idiots,” Vincent said, glancing at Luc with contempt that landed like a slap, “call this number. Ask for Mrs. Vance. Tell her you know what scarpetta means.”

Elena took the paper with fingers that didn’t feel like hers. She whispered thank you, then did what Aurelia had trained her to do: she vanished.

She didn’t vanish far enough to escape Luc.

The moment the Marlowes left, Luc marched to her like a storm with legs. His face was purple, his voice low and poisonous. “You think you’re clever,” he spat. “You think because the old man liked your little stunt, you’re safe?”

“He ate,” Elena said, heat rising in her throat. “He hasn’t eaten in months. That matters.”

Luc’s eyes narrowed. “You humiliated the chef. You served staff food to a VIP. You broke every rule.” He ripped the apron from her waist. “Get out. You’re fired. Don’t bother clocking out.”

Elena stood there holding the apron like a flag torn from a battlefield. Behind her, the kitchen roared, plates clanged, life moved on. In her palm, the page from Vincent’s notebook felt like a key, and she hated that she could feel hope trying to crawl into her chest, because hope was dangerous when you were broke.

Outside, New York’s cold slapped her awake. She walked to the subway with the paper clenched in her fist, repeating one sentence over and over to keep herself from shaking apart: I did the right thing. The city didn’t reward right things, she reminded herself, but it sometimes noticed them.

Julian noticed. From the backseat of the car, he stared at the empty space where Elena had stood, and the look on his father’s face when he’d heard that word. Recognition. Fear. Something like grief. Julian pulled out his phone and dialed his security chief. “Run a background check,” he said, voice cold. “Elena Rizzi. I want everything. And I want to know why my father looked at her like he recognized her.”

Seventy-two hours later, Elena stood in the dim hallway of her Queens building staring at a bright orange eviction notice taped to her door. Luc hadn’t just fired her; he had blacklisted her, and in Manhattan’s high-end dining world, reputations traveled faster than grease fires. Two interviews she’d managed to secure vanished via text before she arrived. Her phone buzzed again with a collection agency number, and she let it ring until it stopped, as if silence could buy time.

Inside her apartment, the air smelled like stale coffee and panic. Elena sank onto her futon, head in her hands, the adrenaline of Aurelia now replaced by the heavy reality of consequences. She had stood up for humanity, and humanity had responded by taking away her rent money.

Her gaze drifted to her wobbly coffee table where the torn notebook page waited like a dare: MRS. VANCE and a number. It felt insane. Vincent Marlowe was famous for crushing unions and bankrupting rivals, the kind of man who treated mercy like a weakness. Whatever warmth had flickered in that restaurant could have been a hallucination brought on by hunger and nostalgia. If she called, best case she’d be rejected by an assistant with an accent sharpened on money; worst case Julian Marlowe would decide she was a threat and send lawyers to erase her.

Then her phone buzzed again. The same collection number. Elena grabbed the paper and dialed before fear could vote no.

It rang twice.

“Private office of the Marlowe Residence,” a crisp voice answered. “Mrs. Vance speaking.”

Elena’s throat tightened. “My name is Elena Rizzi. I… I met Mr. Marlowe at Aurelia. He gave me this number.”

Silence stretched, filled by the faint scratch of a pen. “Elena Rizzi,” the woman repeated, tasting the name as if testing it for cracks. “The waitress with the scarpetta.”

“Yes,” Elena whispered. “That’s me.”

“He’s been expecting your call,” Mrs. Vance said, and there was something almost amused in her tone. “He was beginning to think you had enough sense not to get involved with this family.”

“I almost didn’t,” Elena admitted, and it surprised her how honest the words sounded. “But I’m… I’m desperate.”

“You are,” Mrs. Vance agreed, not unkindly, just factual. “And Luc Duval is vindictive. We assumed he would fire you.”

Elena’s anger sparked. “You assumed and did nothing?”

“We waited to see if you had courage,” Mrs. Vance replied smoothly. “Vincent does not hire cowards. Can you be at the estate in Sands Point by two p.m. today? Gate code is 1949.”

“The estate?” Elena repeated, dizzy. “I thought this might be for a job at one of his companies, or… a restaurant.”

A short laugh snapped down the line. “My dear girl, Vincent Marlowe hasn’t cared about restaurants in thirty years. He doesn’t want a waitress. He wants a memory.”

The line went dead.

Elena spent her last forty dollars on a Long Island Rail Road ticket and a cab, and as the city thinned into suburbs, her anxiety grew teeth. The Marlowe estate rose behind iron gates like a fortress built to keep the world out and guilt in. Ancient oaks lined a long driveway, branches leaning inward like they were sharing secrets. When Elena stepped out of the cab, her thrift-store sweater felt cheaper than air.

The front door opened before she could knock. Mrs. Vance stood there: late sixties, tall, severe, steel-gray hair pulled into a bun so tight it looked like it could cut. Her suit was tailored like armor. Her eyes assessed Elena in a heartbeat.

“You’re thinner than you look on camera,” Mrs. Vance said.

“On camera?” Elena echoed, startled.

“The restaurant footage,” Mrs. Vance replied, already turning away. “Julian had it pulled within an hour. Come inside, Miss Rizzi. We need to talk before the wolf arrives.”

“The wolf?” Elena asked, following her through a marble foyer that smelled like polished stone and old money.

“Julian,” Mrs. Vance said dryly. “He believes he runs this place. He runs the business. I run Vincent. There is a difference.”

Mrs. Vance led her to a library so vast it felt unused, shelves of leather-bound books standing like silent witnesses. Elena sat in a wingback chair that seemed designed to make her feel small, and Mrs. Vance stood by a cold fireplace and laid out the truth like a deck of sharp cards.

“Vincent is dying,” she said. “Not quickly, which is merciful, but slowly, which is torture. His body is failing, but his mind is trapped in regret and nostalgia. Julian believes the solution is to medicate him into compliance and keep him alive long enough to secure quarterly earnings.”

Elena listened, fascinated and unsettled. “And you?”

“I believe Vincent is starving,” Mrs. Vance said. “Not for calories. For meaning. That moment at the restaurant was the first time in five years I saw him present.” She leaned forward slightly, eyes narrowing. “You did not just give him spaghetti. You gave him permission to be human.”

Elena swallowed. “What do you want from me?”

“Be there,” Mrs. Vance said. “Talk to him. Argue with him if you must. Cook for him. Real food. Help him remember why he fought to build all of this. The pay is one hundred fifty thousand a year, room and board, benefits for you and your mother.”

Elena’s heart lurched. “My mother?”

“We know about her condition,” Mrs. Vance said, as if listing weather. “And we can fix it. Vincent wants to.”

Before Elena could process the offer, the library doors slammed open, and Julian Marlowe strode in with the controlled violence of a man used to command. He looked different here than at Aurelia. There he’d been annoyed; here he was predatory, eyes like cold blue flame. He tossed a manila folder onto the table, and photos spilled out like spilled blood.

Elena stared down at her own life laid bare: her walking out of her building, her entering a pawn shop, her mother in a hospital bed in Ohio, her father’s death certificate from a factory accident, the debt he’d left behind like a shadow. Elena felt exposed, violated, but she forced herself to stand.

“Elena Rizzi,” Julian recited, voice dripping with disdain. “College dropout. Three months behind on rent. Mother in end-stage renal failure. You are drowning, Miss Rizzi, and you saw my father as a life raft.”

Elena’s eyes burned, but she refused to cry in front of him. “I didn’t know who he was when I served him,” she said, voice shaking with anger. “I saw an old man who was sad, something you’ve probably never bothered to notice.”

Julian laughed, harsh. “Everyone wants something from the Marlowes. You found his weak spot, the old-country sentiment.” He pulled out a checkbook and wrote quickly. “Fifty thousand. Cash today. You take it, you walk out, and you never speak to my father again. Use it for your mother. It’s more than you’ll make in years.”

He held the check out like a leash disguised as kindness. Elena stared at it, feeling temptation bite, because fifty thousand could stop the eviction, could buy medications, could quiet the collection calls. But the offer carried an insult sharper than poverty: it said her one human moment with Vincent was just a transaction.

She took the check. Julian’s mouth curved, triumphant.

Then Elena tore it in half, then in quarters, and let the pieces flutter down onto the Persian rug like dead leaves.

Julian’s face went blank. “You can’t—”

“You can’t buy scarpetta, Mr. Marlowe,” Elena said quietly. “And you can’t buy me.”

Mrs. Vance watched with something like approval. “When do I start?” Elena asked, and her voice surprised her with how steady it sounded.

Julian stepped forward, towering. “You think you can survive in this house? I will chew you up and spit you out. You will wish you stayed in Queens.”

“Perhaps,” Mrs. Vance said coolly, stepping between them, “but she is Vincent’s guest now. And if you touch her, I will mention the Cayman transfer you made last month.”

Julian froze, color draining, then spun on his heel and stormed out, the doors echoing his fury.

Mrs. Vance finally smiled, and the expression transformed her severity into something almost warm. “Welcome to the asylum,” she murmured. “Now let’s get you an apron. Vincent is asking for risotto.”

The first month at the Marlowe estate became a war of attrition. Julian couldn’t fire Elena, so he tried to break her with a thousand small cruelties: staff instructed to ignore her, heat malfunctioning in her East Wing room, doctors summoned to lecture her about nutrition, paperwork delayed just long enough to make her doubt herself. But Elena had grown up in Ohio on hand-me-downs and stubbornness; cold rooms and judgmental authority were familiar enemies.

The real challenge was Vincent.

Some days he refused to leave bed, staring at the ceiling, muttering Italian so old Elena could barely understand it. Other days he raged, throwing pillows, snapping at nurses, furious at his own failing body. Elena didn’t treat him like a patient. She treated him like her grandfather: when he raged, she snapped back in Italian, calling him a spoiled bambino until shock pulled him into silence. When he sulked, she ignored him and cooked in the kitchenette near his suite, letting the smell do the persuading.

She made peasant food: pasta e fagioli, roasted chicken with rosemary potatoes burnt a little at the edges, polenta with mushrooms, tomato sauce that simmered long enough to become a story. The aroma drifted under Vincent’s door like a hand reaching through darkness. Slowly, almost unwillingly, Vincent began to return to life. He ate. Then he sat by the window while Elena chopped basil. Then, one rainy afternoon, he started talking as if the words had been waiting behind locked teeth.

“Julian doesn’t understand,” Vincent rasped, watching her hands. “He sees deals. He sees numbers. He never saw the fire.”

“The fire?” Elena asked gently.

“The furnace,” Vincent said, eyes distant. “When I first came here, the heat could peel your skin. But we made steel that built this city. We were giants.” His mouth tightened. “Now I am in a golden cage.”

“You built the cage,” Elena said softly.

Vincent glanced at her sharply, then surprised her by not denying it. “Maybe,” he admitted. “But Julian locked the door. He is ashamed of dirt under the nails. He wants everything sterile.” He pointed at a portrait of a woman with elegant, sharp features. “His mother. Old money. She hated garlic on my breath. She tried to scrub Italy out of me. Julian is her son more than mine.”

The confession made Elena’s chest ache. Power didn’t protect you from loneliness; sometimes it purchased a better seat for it. And as Vincent grew stronger, Julian’s panic grew louder. Vincent began joining board meetings again, canceling mergers, questioning decisions, and the market hated uncertainty the way Julian hated losing control.

One evening Elena was in the main kitchen preparing bruschetta when Julian cornered her. Staff vanished instantly, as if his anger had a gravity field.

“You’re poisoning him,” Julian hissed, slamming a hand on the butcher-block island. “His cholesterol is up. Doctors are furious.”

“He’s happy,” Elena said, not stopping her chopping. “For the first time in years he’s laughing. Isn’t that worth a few cholesterol points?”

“He’s erratic,” Julian snapped. “He canceled a billion-dollar deal because the CEO didn’t look him in the eye. You’re winding him up, whispering peasant nonsense in his ear to destroy this company.”

“I think he’s finally seeing clearly,” Elena said, and her calm made him angrier.

Julian grabbed her wrist hard. The knife clattered to the floor. “Listen to me,” he said, breath sharp with scotch. “You think if you make him love you, he’ll change the will. I have power of attorney lined up. I will have him declared incompetent by the end of the week and throw you out with nothing.”

“Get your hands off her.”

The voice wasn’t loud; it was thunder. Julian dropped Elena’s wrist as if burned. They turned.

Vincent stood in the doorway, upright, leaning on a cane with Mrs. Vance beside him. He was shaking with effort, but he was standing, and his eyes blazed with the fury of the young man who once survived furnaces.

“Father,” Julian stammered. “You shouldn’t be walking. The strain—”

“Silence,” Vincent commanded, and the word cracked like a whip. He stepped forward, slow but deliberate. “You think she is here for my money?” he asked, voice low and dangerous.

Julian’s pride surged. “Of course she is. Look at her. She’s nobody.”

Vincent laughed, and the sound was terrifying. “Nobody,” he repeated, shaking his head. Then he looked at Elena with an intensity that was not affection now but something deeper, almost fearful. “Tell me your grandfather’s name,” he demanded.

Elena rubbed her bruised wrist, confused. “Pietro Rizzi,” she said. “My Nonno. Pietro.”

The name hit the room like a physical blow. Vincent’s eyes squeezed shut, and for a moment Elena thought he might collapse. Mrs. Vance tightened her grip on his arm, steadying him. Julian looked startled, as if he’d just watched his father get struck by a memory.

“Pietro,” Vincent whispered like prayer and curse. He opened his eyes and stared at Julian. “You call her nothing. You are wrong.” His cane tapped the floor. “She owns this house. She owns the shirt on your back. She owns every beam of steel we ever built.”

Julian’s face twisted. “This is insane. The dementia—”

“It is not dementia,” Vincent roared. “It is history.” He inhaled, and when he spoke again his voice carried the weight of decades. “Fifty-six years ago, I was starving in a boarding house in Pittsburgh. I needed five hundred dollars to buy into a scrap yard. Five hundred was a fortune.” He looked at Elena, eyes wet with regret. “Your grandfather had saved that money to open his own carpentry shop. Ten years he saved. He saw my hunger and gave it to me.”

Elena’s breath caught. Her Nonno Pietro had died poor, back bent from construction, never owning a shop. She had grown up hearing vague stories of bad luck, of “the American dream being expensive.” She had never heard this.

Vincent’s voice broke. “He made me promise: when you are rich, you pay me back with interest. We shook hands, scarpetta style, man to man.” His eyes trembled. “Two years later I made my first million. I went back to find him. He was gone. I looked for decades. I never found him.” He stared at Elena. “I built an empire on a stolen dream.”

The silence that followed wasn’t polite; it was absolute. Even Julian looked pale, as if money had finally failed him.

Vincent lifted his cane slightly, pointing it like a verdict. “Tomorrow morning,” he said, “I will announce the formation of the Rizzi-Marlowe Trust. Fifty-one percent of my voting shares will be transferred into it.” His gaze cut to Julian. “You wanted to declare me incompetent? Go ahead. But you will do it while cameras watch me repay my debt.”

Julian’s mouth opened, then closed, as if he’d forgotten how to speak without power.

The emergency board meeting two days later took place in a glass-walled room high above Manhattan, where the city looked like a model someone had built for the sole purpose of proving conquest. Elena sat beside Mrs. Vance at a table polished like a black mirror, hands folded in her lap to hide their shaking. She wore a navy blazer Mrs. Vance called armor, but Elena still felt like an impostor, like a waitress who’d wandered into a kingdom and accidentally been crowned.

Julian entered first, sleepless, jaw tight, looking ready to fight the air itself. He placed his hands on the chairman’s chair as if possession could be claimed by touch. Then Vincent rolled in, wearing a vintage charcoal suit that hung a little loose on his thinner frame but carried the weight of who he had been. He didn’t look frail; he looked like a general returning to war.

“Sit down, Julian,” Vincent said.

“I’m the CEO,” Julian snapped. “I chair this meeting.”

Vincent pointed to a small chair at the far end, the kind reserved for someone who took minutes and swallowed opinions. “You sit there,” he said, “or you leave permanently.”

Board members stared at the table grain as if it had suddenly become fascinating. Julian’s pride wrestled with survival, and survival won. He walked, defeated, to the small chair.

Vincent’s gaze swept the room, locking eyes with each director, forcing them to be seen. “You think I am losing my mind,” he began. “You whisper: he is being manipulated by the help.” He slammed a thick leather ledger onto the table. Dust rose like ghosts. “This is not madness. This is accounting.”

He gestured to Elena. “Stand up, Miss Rizzi.”

Elena rose, legs trembling. Dozens of powerful eyes pinned her like specimens. Vincent’s voice sharpened. “Many of you know her as the girl who poured water at Aurelia. You did not look at her face then. Look now.”

A board member tried to protest about earnings calls and market jitters, but Vincent cut him off with a glare that could slice. He told the story of Pittsburgh, of hunger, of a carpenter with five hundred dollars in a tin can under floorboards. He spoke of how banks laughed at his accent and clothes, how Pietro didn’t ask for a business plan, just saw fire and fed it. The room, built for strategy, became a confessional.

When Vincent asked Elena if her grandfather ever got his shop, her voice came out small. “No,” she whispered. “He worked construction. He fell from scaffolding in ’82. He died broke.”

A gasp rippled through the room, because wealth hates learning it was built on someone else’s sacrifice.

“Broke,” Vincent repeated, and the word hung like a guillotine. “While I flew on private jets.” He turned to the board. “The debt is due. With interest.”

Mrs. Vance slid legal documents down the center of the table like a blade. “As of eight a.m. this morning,” she stated crisply, “Mr. Marlowe transferred fifty-one percent of his voting shares into a newly formed entity: the Rizzi-Marlowe Trust. Beneficiaries are the descendants of Pietro Rizzi. Trustees with full voting power are myself and Miss Elena Rizzi.”

Chaos erupted. Directors shouted questions, legal objections, stock implications. Julian stood, face purple with rage. “You can’t do this,” he shouted. “You’re handing the company to a stranger. She’s a waitress!”

“She is the owner,” Vincent roared, silencing the room. Then his voice dropped, quieter and more lethal. “And you, Julian, are an employee, and you are failing.”

Vincent rolled his chair down the length of the table until he was inches from his son. “You wanted to declare me incompetent because I wanted to eat pasta,” he said. “You treated people like machines. You cut steel quality to save pennies. You forgot the soul.”

Julian’s throat worked. “So you’re firing me?”

“No,” Vincent said, and the answer shocked everyone. “That would be too easy. You will remain CEO.” Julian’s eyes flickered with confusion, hope, and humiliation all at once. Vincent continued, “But you will have no vote. You will answer to the Trust.” He turned his gaze toward Elena. “You will answer to her.”

Elena felt the weight of it settle on her shoulders, heavy and unreal, and she understood suddenly that the power she’d stumbled into wasn’t a prize. It was a responsibility her grandfather never got to have.

Vincent’s attention softened as he looked at Elena. “Your mother,” he said, and the room quieted as if everyone sensed this part wasn’t business. “The hospital funds have been wired. She is being transferred to Cleveland. The transplant team is waiting.”

The sound Elena made was not dignified. It was the raw, broken sob of someone whose fear had been a daily companion for years and had just been evicted without notice. She covered her mouth, shoulders shaking, and Mrs. Vance placed a steady hand on her back, grounding her.

Vincent waited, patient. Then he reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out something ridiculous in a boardroom full of luxury: a small plastic container. He set it on the black table and popped the lid.

Inside was tomato sauce, deep red, shining with oil.

Next to it he placed a piece of bread.

“We have a rule in this family,” Vincent said, voice carrying like a bell. “We do not waste the sauce. The sauce is the soul.” His gaze pinned Julian. “You forgot the soul.” He pointed at the bread. “Make the scarpetta.”

Julian hesitated, eyes darting to board members whose approval he’d chased like oxygen. Then he looked at his father, and the strangest thing happened: his face softened, not into surrender, but into something like childhood remembering. He picked up the bread, dipped it into the sauce, and swiped through it messily, staining his fingertips. He ate. He chewed slowly, and Elena watched the taste hit him like a memory he’d been avoiding for years.

“It’s good,” Julian whispered, and it didn’t sound like a compliment. It sounded like grief.

“It’s from the staff meal,” Elena said gently. “Not the fancy version.”

Julian swallowed, eyes lowered. He took another bite.

“Meeting adjourned,” Vincent announced, turning his chair. “Elena. Mrs. Vance. We have work to do.” He glanced back once, voice softer but no less final. “The mill in Pittsburgh needs a visit. I want to show Elena where her grandfather saved my life.”

Weeks later, standing outside the old Pittsburgh mill turned museum annex, Elena watched Vincent’s thin hand touch a rusted beam as if greeting an old enemy. Snow drifted against the building’s brick like time trying to erase things, but Vincent moved through the space with reverence, telling stories not as a billionaire but as a boy who had once been hungry enough to hear opportunity’s heartbeat. Elena listened, realizing her grandfather’s sacrifice had lived inside Vincent all these years like an unpaid debt, souring every victory.

Julian came too, not by choice at first, but because the Trust required it. He stood awkwardly among workers and guides, learning the smell of iron and oil, learning the language of labor he’d treated like background noise. He didn’t apologize to Elena with speeches; he did it with effort, with silence that tried to become something better than his father’s old silence.

One afternoon, in the quiet of a hotel lobby far from Manhattan’s eyes, Julian approached Elena holding two coffees, as if offering something simple was the only way he knew to be human. “My father never told me,” he said, voice low. “About Pietro. About… any of it.”

Elena looked at him, seeing not only the predator but the son, raised by power and shaped by expectation like steel in a mold. “He didn’t want you to know the dirt,” she said. “But dirt is where things grow.”

Julian exhaled, a shaky sound. “I thought control was the same thing as safety,” he admitted. “If I controlled everything, no one could take it from me.” His eyes lifted, raw. “But he was dying in a house full of food, and I didn’t even see it.”

Elena’s bruised wrist had faded to yellow, but the memory hadn’t. Still, she nodded once, because forgiveness didn’t mean forgetting; it meant choosing what you built next. “Then learn to see,” she said. “That’s the only interest that matters.”

By spring, Elena’s mother received her transplant. Elena sat beside her hospital bed in Cleveland and watched her breathe without machines for the first time in years, and she felt her grandfather’s spirit like a hand on her shoulder, heavy with relief. Vincent visited once, moving slowly, eyes bright, and he brought a small container of homemade sauce like it was medicine. “For when she’s strong enough,” he said, and Elena laughed through tears because it was absurd and perfect.

Vincent didn’t live forever. He wasn’t a fairy tale; he was a man. But in his last months, he ate, he talked, he told the truth out loud, and truth has a way of changing the air in a room. When he passed, it wasn’t in a sterile silence surrounded by people afraid to speak; it was in his estate kitchen, where Elena had simmering tomatoes on the stove and Mrs. Vance reading the newspaper aloud, and Julian sitting at the table with his sleeves rolled up like someone finally learning how to exist.

At the memorial, the room was full of powerful faces, but Elena noticed the smallest detail: a bowl of sauce placed beside a basket of bread at the entrance. No one announced it. No one explained it. But people approached, dipped, wiped, tasted, and in that quiet act, a dynasty built on steel and fear remembered, at last, the soul.

Elena kept the Trust. She funded scholarships for trade schools in Pietro’s name. She rebuilt worker safety programs Julian’s cost-cutting had weakened. She visited mills and listened more than she spoke, because she understood now that power without listening was just another kind of silence.

And sometimes, on nights when the city tried to turn everything into plastic again, Elena would make a simple pot of sauce, invite Mrs. Vance and even Julian, and they would sit at the same table, not as conquerors, not as victims, but as people trying to do better with what history had handed them.

In a world obsessed with polished plates, the Marlowe empire was saved by something messy: a piece of bread wiping up what mattered most, refusing to waste the soul.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load