They always told the tale the same way, like it belonged to the fire more than it belonged to any one mouth. In the Colorado Territory, where a man could ride for two days and still see the same line of mountains staring back at him, stories traveled faster than horses. They slipped through saloon doors on cold wind, sat down uninvited at card tables, and warmed their hands at campfires with tired travelers who wanted something to believe in besides hunger and weather. And the story that clung to the mountains like pine sap was the one about Jonah Granger, the high-country trapper who lived where the spruce grew tight and the air turned sharp enough to bite your throat. They said he’d built his cabin out of logs so thick they looked like a fort, roofed it with timbers that winter couldn’t pry loose, and set it in a clearing that only the bold or the foolish ever found. They said he hunted elk alone, fought off wolves the way other men swatted flies, and came down into Silverpine Valley only when he needed salt, shot, or iron. When he did, folks watched him like they were watching a storm decide where to land.

Jonah wasn’t famous because he was big, though he was, broad as a barn door with a beard like a dark curtain and hands that looked carved from old knots of oak. Jonah wasn’t famous because he didn’t talk, though he didn’t, giving most questions nothing but a flat look that made people suddenly remember they had somewhere else to be. Jonah was famous because of the women. Every few months, a stagecoach would rattle into the valley carrying another mail-order bride, wrapped in fresh fabric and thin hope, clutching a carpetbag and a letter that promised a home in the mountains. Some of them arrived in white gloves that never touched dirt until the moment they stepped out. Some wore bonnets pinned so tight you’d think propriety could keep out fear. All of them smiled the same tight smile, as if they could convince the world and themselves that a stranger’s cabin might become a life. And all of them, without fail, were gone within seven days.

The valley counted them the way it counted seasons. “That makes five,” the barber would say, shaking his head. “That makes six,” the grocer’s wife would whisper, crossing herself. “That makes seven,” the bartender would mutter, sliding a whiskey down the counter with the kind of respect you give to bad luck. Rumors grew teeth. Some said Jonah was cruel, that he wanted a servant more than a wife. Others claimed he was half-wild, not fit for a woman’s softness. A few men, the kind who enjoyed gossip because it kept them from looking at themselves, leaned in and said, “Maybe he scares them on purpose,” like that made it less ugly. No one knew the truth, because Jonah didn’t explain himself, and the women who returned had the same distant look in their eyes, as if the mountain had spoken a language they couldn’t bear to translate. By the time the seventh bride slipped away before dawn, leaving only footprints in frost and a wedding band on a table, people stopped saying “unlucky” and started saying “cursed.”

That’s how the tale began, with everyone certain they knew how it would end. Then, in the early fall of 1878, a different kind of woman climbed into the stagecoach in St. Louis with nothing delicate about her except the one small place in her chest she’d stopped admitting was there. Her name was Abigail Lane, though back home her brothers had called her “Big Abby” with the lazy cruelty that feels like truth when you hear it long enough. She’d grown up round-faced and wide-hipped, with hands better suited to kneading dough and hauling laundry than fluttering at dances. Boys had ignored her unless they needed someone to laugh at, and girls had learned to treat her like a cautionary tale. Even her own mother spoke to her with a weary edge, like Abby was a chair taking up too much room in a house already short on space. When the letter came, inked in careful script by a matchmaking agent, promising a “strong husband, steady homestead, and honest work,” Abby didn’t ask if she was wanted. She asked if she could leave.

By the time the stagecoach began its long climb toward Silverpine Valley, Abby’s body ached from the road and her pride ached from the memories she carried like stones in her pockets. The driver, a leathery man named Hank McCall who smelled of tobacco and horse sweat, had driven enough hopeful brides into the mountains to recognize the look in their eyes. On the second day, when the mountains rose ahead like a wall and the air turned thin enough to make the lungs complain, Hank spit out the side and said, not unkindly, “Miss Lane, you sure you want this?

Folks say no bride lasts a week with Jonah Granger. Mountain swallows ’em whole.” He didn’t try to frighten her for sport; he sounded tired, like warning people was a chore the world kept assigning him.

Abby stared out at the pines and the rock and the sky that seemed too close, then lifted her chin as if the mountains were another person trying to decide if she belonged. “I’ve been swallowed before,” she said, voice steady. “Came out with my bones still mine.” Hank grunted, scratching his jaw. “Most of ’em say somethin’ brave in the coach,” he replied. “Then they see him.” Abby’s mouth tipped into a small, sharp curve. “Then he’ll see me,” she said, and something in that sentence, the way she didn’t ask for permission inside it, made Hank glance at her like she was a puzzle that might not break the way the others had.

When the coach finally creaked to a stop at the edge of the valley, the air snapped cold though winter hadn’t arrived yet. Abby stepped down onto hard-packed earth, boots sinking just enough to remind her that this land didn’t care about softness. A split-rail fence marked the start of a narrow trail that climbed into the trees, and leaning there, as still as a post, stood Jonah Granger. The stories hadn’t exaggerated him. He was massive, shoulders stacked with muscle from years of chopping and hauling, beard untrimmed and dark, eyes a pale gray that looked like river ice. He didn’t smile. He didn’t lift a hand in greeting. He just studied her the way a man studies weather, trying to decide what kind of storm it will become.

Most women would have shrunk under that stare, feeling suddenly smaller than they’d ever felt. Abby didn’t shrink. She tightened her grip on her carpetbag, squared her shoulders, and walked forward until she was close enough to smell woodsmoke on him. Jonah didn’t move. He didn’t offer to help with her bag. Silence sat between them like a third person, smug and heavy. Abby glanced back at Hank, who was already wearing the look of a man planning a return trip. Then Abby faced Jonah again and said, “Well? You going to help me with my bag, or are we starting this marriage with me carrying all the weight?”

Hank choked on his own spit, half expecting Jonah to explode. Jonah only blinked once, slow, as if Abby had spoken in a language he hadn’t heard in years. Then he reached out, took the carpetbag as though it weighed nothing at all, and turned toward the trail without a word. No welcome. No vow. Just movement. Abby followed, boots crunching on gravel, breath growing heavier as the path narrowed and climbed. Behind them, Hank shook his head and muttered, “Poor woman,” but Abby didn’t hear. And even if she had, she’d have treated it like rain: something you feel, something you endure, not something that gets to decide your direction.

The climb to Jonah’s cabin was a test, and the mountain didn’t bother pretending it was anything else. The trail twisted through pine and spruce, steep enough to make Abby’s calves burn and narrow enough that one wrong step would send a person tumbling into rock and brush. Jonah’s stride was long and relentless. He didn’t look back to see if she struggled. He didn’t offer a hand at the slickest turns. Abby’s dress snagged on branches, her breath came in rough pulls, and blisters began forming under her heels like small punishments. Still, she kept going, because she’d learned long ago that if you wait for the world to make things gentle for you, you’ll die sitting down.

When the trees finally opened into a clearing, the cabin stood there like a challenge made of logs. It was solid, squat, and built to endure. Firewood was stacked high along one wall. Pelts hung drying on racks. A thin wisp of smoke curled from the chimney into a sky already pale with coming cold. Abby planted her hands on her hips and took it in. “So this is where brides come to disappear,” she muttered, not loud enough to be polite, not quiet enough to be hidden.

Jonah paused near the door, his head turning just enough for one gray eye to catch hers. “They left because they weren’t built for it,” he said flatly, voice deep and rough like rocks grinding together. “If you’re smart, you’ll do the same before snow sets in.” Abby’s chest rose and fell hard from the climb, but she managed a snort. “You don’t scare me, Jonah Granger,” she replied. “I’ve lived through worse than cold walls and hard work.” Jonah said nothing more. He shoved open the heavy door and stepped inside.

The cabin smelled of smoke, pine resin, and the faint metallic tang of old iron. Inside, it was exactly what Abby expected: rough-hewn furniture, a wide stone hearth, animal skins thrown over floorboards for warmth. There were no curtains, no softness, no little signs of anyone trying to make beauty where survival was the main language. Jonah dropped her bag by the wall and looked at her like he was reading a list no one else could see. “You’ll cook,” he said. “Mend. Keep the fire. I’ll hunt. Chop. Keep wolves off the door. Don’t expect more than that.” It wasn’t a proposal. It was a division of labor.

Abby lifted her eyebrows. “Well,” she said, voice dry, “isn’t that the kind of romance a woman crosses a continent for.” Jonah’s jaw tightened as he pulled a knife from its sheath and began sharpening it on a stone. The scrape filled the silence, sharp and steady. Abby waited a beat, long enough to see he wasn’t going to fill the air with anything else, then walked straight to the hearth. “Fire’s low,” she announced. “Either you like breathing, or you enjoy freezing. I’m stoking it.”

She gathered logs, split kindling with a small hatchet she’d spotted by the wall, and had the fire crackling within minutes. Heat spread into the room, softening corners, turning the cabin from fortress to something closer to shelter. Jonah’s sharpening slowed for half a second, his eyes flicking to her hands, to the sure way she moved. The other brides, Abby guessed, had stepped inside and started looking for curtains that weren’t there, a softness that had never been promised. They’d shivered and complained and tried to talk Jonah into being someone else. Abby didn’t have energy left for pretending a mountain man was meant to behave like a parlor gentleman. She cared about warmth, food, and not being sent away like a cracked dish.

That night, Jonah tossed her a wool blanket. “You take the bed,” he said. “I’ll sleep by the fire.” Abby blinked, surprised not by the offer itself but by the blunt honor inside it. “You don’t have to,” she started. Jonah’s eyes narrowed. “I said you take it,” he replied, like refusing would be an insult. Abby nodded once. “Fine. But if your back freezes stiff, don’t blame me when you start walking like an old mule.” Jonah grunted, which might have been annoyance or amusement. Abby climbed into the narrow bed, pulled the quilt up, and stared at the log ceiling while wolves howled in the distance. For the first time since she’d left home, she didn’t feel like she was taking up too much space. The cabin was rough, the man was rougher, but the mountain wasn’t laughing at her. The mountain was simply asking: Are you going to stay?

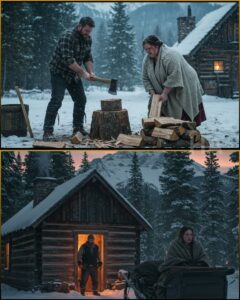

The next morning, the answer was written in work. Jonah was already outside, splitting wood with swings so clean each log cracked in a single blow. His shirt clung to his shoulders with sweat despite the chill. Abby stepped into the doorway, rubbed sleep from her eyes, and called, “If you plan to work me to death, you’d better let me eat first.” Jonah paused, axe buried in a stump. Slowly, one corner of his mouth twitched, not quite a smile but close enough to count as a crack in stone. “Breakfast,” he said. One word, and it landed in Abby’s chest like a strange gift: an acknowledgment.

The first week didn’t test muscle so much as it tested pride. The work was endless, but Abby didn’t mind labor. She’d spent her life earning her place by being useful, because nobody had ever offered her a place just because she existed. What grated was Jonah’s constant criticism, the way his silence wasn’t peaceful but crowded with judgment. “Fire’s too low.” “Logs are cut too short.” “Stew’s on too early.” He didn’t shout. He didn’t curse. He just delivered each complaint like a hammer tap, steady enough to build a wall between them.

On the fourth evening, Abby finally set the spoon down hard enough to make the table jump. “You know,” she said, planting her hands on her hips, “for a man who lives alone, you sure do complain like you’ve got an audience.” Jonah didn’t lift his head from the knife he was sharpening. “If I wanted it wrong,” he replied, “I’d cook it myself.” Abby’s cheeks flushed hot. “Then do it,” she shot back. “Go on. Cook it. Sharpen your knife, cook your stew, and keep your precious silence. But don’t you sit there acting like you invited me here to be your punching bag for every unhappy thought you’ve ever had.”

For a long moment, Jonah went still. The cabin’s fire popped and cracked, a small, defiant sound. When Jonah finally looked up, his eyes were sharp, but there was something else under the edge, something almost startled. “You’re the first one to raise your voice at me,” he said, not as a threat, but as if he couldn’t quite believe it was allowed. Abby didn’t blink. “Then maybe you needed someone who wasn’t afraid of you,” she said. Her voice softened just a notch, because anger, she’d learned, was often grief wearing boots. “Or maybe you needed someone who’d stop letting you hide behind grunts.”

Jonah’s jaw worked as if he were chewing on words he didn’t like the taste of. Then, slow as snow sliding off a roof, his shoulders eased a fraction. He pushed the bowl back toward her. “It’s… fine,” he muttered. “I’ll eat it.” Abby’s mouth tugged into a smirk, though her eyes stayed serious. “That’s right you will,” she said, and the air shifted, not into comfort yet, but into something less lonely than before.

Then winter arrived early, as if the mountain had been watching them argue and decided to throw in its own opinion. Thin flakes turned into heavy snow. Trees bowed under white weight. The cabin became a small island of smoke and fire in a world that wanted to freeze everything into silence. Jonah doubled his hunts, hauling back rabbits, elk, whatever he could trap. Abby salted meat, dried strips by the hearth, and stacked jars and sacks against the wall. Their movements turned rhythmic, like a shared language neither of them had to admit they were speaking.

When the blizzard came, it came like a beast. Wind hurled snow at the cabin walls so hard the shutters rattled and the roof groaned. For three days they were sealed in, the door buried behind a drift taller than Abby. By the second day, the food looked thinner than it should have, not because Jonah hadn’t prepared, but because winter always demanded more than you planned for. That night, Abby made a broth so light it barely had color. She filled Jonah’s bowl a little more than her own and tried to act like it meant nothing.

Jonah noticed. His spoon paused midair. “You didn’t take your share,” he said. Abby shrugged, blowing steam off her bowl. “I don’t need much,” she lied. “Besides, you burn more. You swing axes. You fight wolves.” Jonah’s gaze sharpened. “Don’t starve yourself,” he said. Abby’s chin lifted. “I’ve had less and lived,” she replied, which was true enough to sting.

The next night, she did it again. Jonah slammed his spoon down so hard the sound cracked through the cabin. Abby jumped, then glared back, offended at herself for flinching. “You’ll waste away before you quit,” Jonah growled. Abby’s voice rose, a flare against the storm. “Better to starve than to live like a coward,” she shot back, and the word coward hung in the air like smoke you couldn’t wave away.

It struck Jonah harder than the wind. For a long moment, he stared at her as if he was seeing not just a stubborn woman but a mirror. Then his shoulders sagged, and for the first time, Jonah looked less like a legend and more like a man carrying something heavy. Later, in the deep night when the storm still raged, Abby woke to find him sitting by the fire, eyes fixed on the flames. She sat up, quilt pulled tight. “You don’t sleep much,” she said quietly.

Jonah’s jaw shifted. “Sleep don’t come easy when you’re waiting for the roof to fall in,” he answered. Abby studied his profile, the hard lines, the old scars. “You’ve been alone too long,” she murmured. Jonah turned his head, the firelight catching in his gray eyes. “And you’ve been hurt too much,” he said back, voice rough but not cruel. The silence that followed wasn’t cold. It was fragile, like a bridge made of thin wood that might hold if neither person stomped.

By the fourth day, the blizzard broke. The world outside was white and still, sunlight weak as a tired promise. Jonah dug a path to the woodpile, his breath steaming, his movements fierce with the relief of action. Abby stood in the doorway wrapped in a blanket, watching him, and realized something that unsettled her: she didn’t see only danger in him anymore. She saw protection. Not the kind that caged, but the kind that stood between you and a world that had already decided you were expendable.

That realization caused another one, because hearts are rarely content with one truth at a time. If Jonah was capable of protecting, then something had once threatened him enough to make him build walls this high. Abby didn’t ask at first, because she knew pushing a wounded animal too fast only made it bite. But one night, when the wind was gentler and the cabin felt almost quiet in a human way, Jonah finally spoke without being provoked. “Why’d you come?” he asked, voice low, almost wary. “You heard the stories. You knew no bride stayed.”

Abby poked the fire with an iron rod, sparks leaping. Her face softened into something she didn’t show often. “Because nowhere else wanted me,” she said simply. “Back home I was too much of everything. Too big. Too loud. Too stubborn. They said I’d die an old maid, and I believed them. So when I got the chance to come here, I figured if I was going to be unwanted, I’d rather be unwanted where the air is clean and a man works honest.” Her voice tightened at the end, and she hated herself for it, hated that old habit of feeling ashamed for wanting anything.

Jonah stared at her a long time. When he spoke, it was almost a whisper. “You’re not unwanted here,” he said. Abby blinked. “What?” Jonah’s gaze dropped, as if he’d said too much. He reached for his knife and stone, the old habit returning like a shield, but his strokes were slower now, less sure. Abby let the words settle into her bones anyway, because she’d survived on scraps of kindness before and learned how to stretch them into something warm.

Spring didn’t arrive all at once. It crept in, stealing snow from the edges, turning the ground into mud, waking the forest animals and, with them, the men Jonah had been watching for days. Smoke began rising in places it didn’t belong. Strange tracks cut across hunting grounds. Jonah’s shoulders grew tense, his movements sharper, his eyes scanning tree lines with the patience of a man who’d been hunted before. Abby noticed the change because living with Jonah had taught her to read what he didn’t say. One afternoon, while Abby scrubbed clothes by the riverbank, Jonah appeared out of the trees with a rifle on his back. “You shouldn’t be out here alone,” he said, scanning the woods like he expected them to blink.

Abby straightened, water dripping from her hands. “What’s out there?” she asked, though a piece of her already knew. Jonah’s jaw clenched. “Men,” he muttered, the word heavy as a stone. That night, Abby cooked supper with her nerves humming under her skin. Jonah kept glancing at the window as if shadows might grow teeth. Finally, Abby set the ladle down and faced him. “Tell me,” she demanded. “Don’t leave me guessing like I’m a child.”

Jonah hesitated. Explaining himself was not a skill he’d kept sharp. But Abby was here, and winter had already taught him that pretending she wasn’t part of his life didn’t make it true. “Drifters,” he said. “They take what they want. Food. Furs.” He paused, and the pause itself was a warning. “Women.” Abby’s throat tightened. She didn’t flinch, because fear was easier to manage when you named it. “You think they’ll come here,” she said.

Jonah met her gaze. “They’ll try,” he replied.

The next morning proved him right. Abby was hanging laundry when she spotted them: three rough-looking men climbing the slope, rifles slung careless, smiles wide and ugly. “Afternoon, miss,” the tallest called. “Didn’t know the mountain man kept such a pretty housekeeper.” The word housekeeper landed like spit. Abby’s hands stilled on the cloth. Her heart thudded hard, but she stood straight. Before she could answer, Jonah stepped out of the cabin, rifle already in his hands, presence filling the clearing like thunder.

“You’re trespassing,” Jonah said, voice low and deadly calm. The tallest man smirked. “Easy now. We just came to visit,” he said, gaze sliding to Abby like she was merchandise. “Maybe share a drink. Maybe more.” Jonah cocked the rifle without hesitation. The click cut through the air. “Leave,” he said. “Now.”

For a tense moment, nobody moved. Then the tall man laughed and spat into the snow. “Fine,” he said, backing away slow. “But don’t think you can keep us out forever. Sooner or later, mountain man, everybody bends.” Their laughter drifted down the slope, ugly as crows.

Inside, Abby’s hands shook as she poured water, anger and fear braided tight. “They’ll be back,” she whispered. Jonah sat at the table cleaning his rifle with steady, deliberate strokes. “They’ll be back,” he confirmed. Abby swallowed. A part of her, the old trained part that believed she was trouble simply by existing, rose up. “Maybe I should go,” she said, hating herself for saying it. “Maybe I’m making it worse for you.”

Jonah snapped the rifle shut, the sound sharp. “No,” he said, and the word wasn’t just refusal, it was claim. His eyes burned into hers. “You’re not leaving.” Abby’s breath caught. Jonah leaned forward, voice dropping. “You stayed when no one else did. You faced me. You faced this life. If they think they can take you from me, they’ll find out what it means to fight a mountain.”

That night, the cabin held a different kind of silence, not strangers’ silence, but the taut quiet of two people waiting for a storm. Abby sat by the fire, mending forgotten in her lap, and watched Jonah sharpen his hunting knife, his shoulders rigid with contained violence. She realized something else then, something that made her feel both small and fierce: Jonah’s protection wasn’t pity. It was respect. He believed she belonged here enough to defend her place in it.

Three days passed, too quiet. Jonah rose earlier, checked traps twice, and laid fresh logs by the door. On the fourth morning, dogs barked sharp and frantic. Then came the crunch of boots on frozen ground. Abby dropped the bread dough she’d been kneading, flour puffing up like smoke. “Jonah,” she whispered.

He was already at the door, rifle in hand. His voice came out calm but hard. “Stay behind me,” he said, and Abby did for half a heartbeat, until she remembered she hadn’t come this far to be treated like something fragile. Five men climbed into the clearing, the same three plus two more, and one carried a coil of rope like he was already planning the end. “Well, well,” the tall one sneered. “Told you we’d be back. Mountain man’s hiding a wife now. Ain’t fair he gets to keep all the sweetness.”

Abby’s stomach turned, but she stepped forward enough for them to see her face, not because she wanted to challenge them, but because she refused to be erased. Jonah lifted his rifle. “You step closer,” he said, “and you’ll leave in the ground.”

They laughed, spreading out, circling like wolves testing for weakness. Then everything happened fast. One man lunged left, another right. Jonah fired, the crack echoing through the pines, dropping one man with a scream. Another surged forward, and Abby’s body moved before fear could tie her feet. She grabbed the iron poker from the hearth and swung hard when a hand grabbed her arm. The poker connected with a sickening crack. The man stumbled back cursing, clutching his jaw.

Jonah fought like the mountain itself, brutal and unmovable. He slammed one attacker into the cabin wall, fists breaking bone. He swung the rifle butt into another man’s skull with a sound like splitting wood. “Abby!” he shouted, tossing her a hunting knife. She caught it clumsily, heart hammering. A man charged at her, and for the first time in her life, Abby didn’t freeze. She slashed, not deep, but enough to make him roar and retreat, blood dark against snow.

The fight was chaos, then it was over. Two men limped away dragging the wounded. The rest lay groaning in the clearing, too broken to rise. Jonah stood in the middle of it all, chest heaving, knuckles streaked with blood. His eyes snapped to Abby. “You hurt?” he demanded.

Abby shook her head, hands trembling around the knife. “Not a scratch,” she said, then something wild burst out of her, half laugh, half sob. “Lord above, Jonah,” she panted, “I thought I’d faint. But I didn’t.” Jonah stared at her like she was a miracle he didn’t know what to do with. Her hair was tangled, apron torn, cheeks flushed with fierce life, but she was standing. Still standing.

“You stayed,” Jonah murmured, voice cracking on the word. “No one ever stayed.” Abby’s eyes shone wet, but her gaze didn’t waver. “Then let me be the first,” she whispered.

Something in Jonah broke, the walls he’d built higher than peaks. He crossed to her in two strides, one massive hand cupping her face, his thumb rough against her cheek. “Abby,” he breathed, and her name sounded different in his mouth, like it belonged there. Then he kissed her, not soft, not careful, but raw with the kind of hunger that isn’t just desire, it’s relief, it’s grief finally letting go of its grip. Abby clung to him, not minding the blood on his shirt or the smoke in the air, because she understood something she’d never understood back in St. Louis: wanting love didn’t make her weak. Refusing to leave didn’t make her stubborn for no reason. It made her brave enough to claim a life.

Afterward, when the wounded men had been bound and dragged down to the valley to face the marshal, the story began to change. Folks who’d once whispered “cursed” started whispering “tamed,” but Abby corrected them every time she heard it. “I didn’t tame him,” she said, hands on hips, eyes bright. “I met him. There’s a difference.” Some people laughed like they didn’t know what to do with a woman who spoke that plainly. Others, especially the women who’d lived too long swallowing their words, looked at Abby like she’d opened a window in a room they thought had no air.

Jonah, for his part, didn’t suddenly become gentle. He didn’t start making speeches or buying ribbons. But he began doing small things that mattered more than romance. He built a shelf low enough for Abby to reach without stretching. He cut kindling before she asked. He brought her a blue jay feather once, set it on the table, and said, “Thought you might like it,” then went back outside before his face betrayed how much it cost him to offer anything tender. Abby kept that feather in her Bible even though she hadn’t read the Bible much in years. She didn’t keep it for religion. She kept it as proof that a hard man could learn softness without losing strength.

When spring finally settled fully into the mountains, Abby planted a small garden near the cabin, stubborn green pushing through dirt like a promise. Jonah watched her one evening, arms folded, and said, almost grudging, “Never seen anyone make life grow up here.” Abby wiped sweat from her brow and replied, “That’s because you’ve been calling this place a fortress instead of a home.” Jonah’s eyes narrowed. “And what do you call it?” he asked.

Abby looked at the cabin, at the clearing, at the trees that had once felt like judges and now felt like guardians. She thought of the girl who’d climbed into a coach believing she was a burden, and the woman who’d swung a poker at a man with rope in his hand. She thought of Jonah’s voice saying, You’re not unwanted here, and realized she’d started to believe it. “I call it ours,” she said.

Jonah didn’t answer right away. He stepped closer, took her flour-dusted hand in his scarred one, and squeezed once, as if making a vow without the noise of vows. And in that quiet gesture, Abby understood the human shape of their miracle: it wasn’t that she’d become small enough to be loved, or that Jonah had become easy enough to keep. It was that two cast-off people had stopped agreeing with the world’s verdict. They had built something sturdier than gossip, sturdier than fear, sturdier than winter.

That summer, when travelers stopped in Silverpine Valley and asked for the famous mountain man, the townsfolk still told the story, because people will always tell stories. But the ending was different now. They didn’t say no bride lasted a week. They said one woman arrived with a plain dress, a sharp tongue, and a spine made of iron, and she refused to leave. They said she didn’t fix Jonah Granger like he was broken furniture. She stood beside him until he remembered he was human, and then he stood beside her until she remembered the same. And if a traveler scoffed, if a man tried to laugh at the idea of an “obese bride” becoming a legend, the women in town would look him dead in the eye and say, “Careful. The mountain has ears. And that woman? She’s part of it now.”

On the first cool night of autumn, almost a year after Abby arrived, Jonah lit a fire outside the cabin and sat with Abby beneath a sky thick with stars. He handed her a tin cup of coffee and said, voice low, “I drove them away on purpose.” Abby didn’t flinch at the confession. She waited, letting him find the rest. Jonah stared into the flames. “Long before you,” he said, “I had a wife. She died in a winter storm. I kept thinking if I loved someone again, the mountain would take her too. So I made sure nobody stayed long enough for me to care.” His throat worked. “I thought loneliness was safer.”

Abby reached out and covered his hand with hers, warm and steady. “Loneliness isn’t safe,” she said quietly. “It’s just familiar.” Jonah’s eyes lifted to her. “Why didn’t you run?” he asked, and there was a boyish bewilderment under the man’s roughness, like he still couldn’t believe the world had handed him something good.

Abby breathed in pine smoke and mountain air, then answered with the simplest truth she owned. “Because I was tired of being sent away,” she said. “And because when I looked at you, I didn’t see a curse. I saw a man who needed someone to stay.” She smiled, slow and sure. “And Jonah… I needed someone to let me.”

Jonah’s thumb brushed her knuckles, and his mouth, that stubborn mouth that had withheld warmth for years, curved into a real smile at last. Not big. Not polished. But real, like sunrise breaking through cloud. “Then stay,” he said, voice thick, as if the word carried every prayer he’d never spoken. Abby squeezed his hand back. “I already am,” she replied.

The fire crackled. The mountains stood tall, indifferent to human drama, yet somehow less lonely for the two small figures sitting in their shadow. And in the vastness of that wild country, where people often vanished without leaving proof they’d mattered, Abby Lane Granger sat beside a man everyone had feared and decided, with all the stubbornness that had ever been used against her, that her life would not be a story of leaving. It would be a story of staying, of building, of refusing the world’s small definitions, and of turning a fortress into a home.

THE END

News

HE MARRIED HIS OWN ENSLAVED COOK AS A BET… AND THE BAYOU KEPT THE RECEIPTS

The marriage certificate still exists in Baton Rouge, in a quiet room where history is kept like old bone. Paper…

THE PLANTATION LORD HANDED HIS “MUTE” DAUGHTER TO THE STRONGEST ENSLAVED MAN… AND NO ONE GUESSED WHAT HE WAS REALLY CARRYING

The Georgia sun didn’t shine so much as it ruled. It pressed down on Whitaker Plantation with the confidence of…

He Dumped Her For Being Too Fat… Then She Came Back Looking Like THIS

In Mushin, Lagos, there are two kinds of mornings. There’s the kind that smells like hot akara and bus exhaust,…

End of content

No more pages to load