Central Minnesota, was the kind of place that asked your body questions every day and expected honest answers.

Can you walk through a wind that cuts sideways?

Can you split enough wood when your hands feel like stiff leather?

Can you keep a child alive when the world turns into one long, white breath?

On a morning when the snow underfoot sounded like broken glass, the settlers gathered the way people gather for two reasons: worship and witness. This wasn’t Sunday. This was the other kind.

They came to watch a Swiss immigrant named Johan Meyer do something “wrong” with the full confidence that wrongness would eventually punish him in public.

A stone barn, twelve feet tall, walls thicker than any sensible man’s patience. And on top of it, like a hat perched on a giant’s head, a log cabin.

“It’s like he’s building a wedding cake for cows,” someone muttered, and the laugh that followed had the sharpness of cold metal.

Johan heard them, of course. He heard everything. But he kept his gloves on, kept his eyes on the line he’d snapped across granite, and kept lifting stone like it was a language he still trusted more than English.

Elizabeth Meyer stood near the wagon, her shawl pinned tight. The children stayed close to her skirts, their noses pink, their breath puffing out in small clouds. Their little boy, Matthias, peered between adults’ legs as if expecting the cabin to topple like a toy.

Johan straightened, wiped frost from his mustache, and spoke to his wife as if they were alone.

“We’ll have it closed in before the real bite comes,” he said.

Elizabeth’s eyes flicked to the line of onlookers. “Before the real bite,” she repeated softly. “As if this is only the gum.”

Johan’s mouth twitched. Not a smile, not quite. More like a hinge remembering how to move.

A horse snorted below as if agreeing.

From the crowd, Carl Larson rode closer on his sorrel, boots creaking on the stirrups. Carl was the sort of man who believed good sense was a fence line and anyone outside it was either a fool or a sinner.

He didn’t bother lowering his voice.

“Johan,” he called, drawing out the name like it was too foreign to sit properly in his mouth. “Winter’s coming fast. You should’ve built a proper cabin months ago.”

Johan looked at him, calm. “I am building a proper cabin.”

Carl gestured, wide and incredulous, to the stone walls rising from frozen ground like a fortress. “That contraption will be the death of you. Living above animals like that… it’s unsanitary. Uncivilized.”

Tom Wagner, passing with a wagon of split logs, slowed just enough to join the show. “That’s enough stone for three cabins,” Tom said, not cruelly, but with the bafflement of a man watching someone choose the long road on purpose. “And you’re putting your cows right under where you’ll eat and sleep? My wife would faint dead away.”

A few women tittered behind their mittens.

Elizabeth’s cheeks reddened, though whether from cold or insult was hard to tell. She leaned toward Johan. “They’re going to talk no matter what,” she whispered.

Johan nodded once, slow. “Let them talk,” he said. “Talk doesn’t keep a house warm.”

It wasn’t stubbornness that held him there in the wind. It was memory.

He had grown up in a house-barn in the canton of Bern, where the winter didn’t arrive like a visitor, but like a verdict. In that old stone building, animals breathed and shifted below, their warmth rising into the family’s rooms like a quiet, faithful tide. His mother had churned butter without her fingers cracking. His grandfather had said, more than once, that a cow was worth two stoves and ate nothing but grass and hay.

When Johan came to America, he found men building as if forests were endless and cold was only a nuisance, something you swore at while pouring another log into the fire. Here, people fought winter with flame. In the Alps, they fought winter with design.

Design was slower. Design was mocked. Design didn’t look heroic in the moment.

But design worked at three in the morning.

So Johan kept laying stone.

For three months, his days were measured by muscle and mortar: quarry granite from a nearby outcrop, haul it by ox cart, fit each fieldstone with the methodical precision his father had drilled into him. He burned his own lime for mortar. He set the walls eighteen inches thick, not because he liked extra work, but because the stone needed to do more than hold weight.

It needed to hold warmth.

Every stone was a promise that the heat produced down below would not escape in a single shiver of wind. The foundation was not a basement. It was a battery.

Carl Larson saw only inconvenience. “You’ll freeze before you finish,” he told anyone who would listen. “And if you don’t freeze, you’ll choke on stink.”

Johan didn’t argue. Arguing made you spend breath you might later need.

Instead, he built ventilation openings where they mattered. He planned a central stone chimney like a spine, meant to pull fresh air through the livestock quarters, warm it, and send it upward without allowing cruel drafts to knife through the living space. He laid thick pine floorboards with narrow gaps that looked, to the untrained eye, like sloppy workmanship.

They weren’t.

They were little doors for heat.

By late September, when most settlers had already sealed their cabins and stacked wood for winter, Johan was still raising the cabin portion. Barn-raising day drew nearly every family within ten miles, not out of pure generosity, but because people could not resist a spectacle.

Men lifted logs into place, their breath steaming. Women clustered with baskets of food and gossip. Children chased each other around the stone walls and got shouted back before they could tumble into a mortar bucket.

Elizabeth served coffee and a pan of strudel she’d guarded like treasure through the move west. She smiled when thanked, kept her chin level when whispered about.

“Unnatural,” one woman said behind her hand, eyes flicking toward the open lower level where the animals would live. “Living above beasts like that.”

Another replied, “What will they think of next?”

Elizabeth pretended not to hear, but her fingers tightened around the coffee pot handle.

Johan, balancing on a beam, called down to her. “Lisbeth,” he said in the Swiss German that was softer in his mouth, “is everything all right?”

She looked up and gave him the smile she used when she wanted their children not to notice her worry. “Everything is fine,” she said, then added quietly in his own language, “They think we’re dirty.”

Johan’s answer was not comfort in the easy sense. It was steadiness.

“Let them,” he said. “Cleanliness is work, not distance.”

That night, after the last neighbor trudged home and the prairie swallowed their lantern lights, the Meyers sat inside the half-finished cabin with the children wrapped in blankets. Wind pressed against the logs like a persistent creditor.

Elizabeth watched Johan draw diagrams in the ash on the hearthstone.

“Do you ever get tired of being certain?” she asked.

Johan looked at her, surprised. “I am not certain,” he admitted. “I am… committed.”

She exhaled, a little laugh turning to fog. “That’s a dangerous kind of faith.”

“It is not faith,” he said. “It is remembering what worked where I came from.”

“But this isn’t Bern,” she said, not accusing. Just naming the fear.

Johan reached across the space and took her hand. His palm was rough, his grip gentle.

“No,” he said. “This is Minnesota. The cold speaks English here. But it still obeys the same laws.”

October came with a hard frost that blackened the garden and made the creek edges clatter with thin ice. Johan moved the livestock into the stone-walled lower level: ten head of cattle and horses, bedded on thick straw he’d stacked high all summer. He adjusted the ventilation openings, checked drainage, and sealed any gaps that would turn into wind tunnels.

His neighbors watched the final preparation as if witnessing a man invite trouble to dinner.

Carl Larson’s voice carried across the snow-dusted prairie. “Mark my words,” he told Tom Wagner and anyone else nearby, “that family will be sick all winter from stench and filth. And when the real cold comes, they’ll freeze like the rest of us, except they’ll have to listen to cows bawling while they shiver.”

Johan heard him. He did not look up from his work.

Instead, he spoke to the animals as he spread fresh straw.

“Easy,” he murmured, his voice low, the way you speak to living things you depend on. “We will keep each other alive.”

When November’s first serious snow arrived, it came quietly at first, like a soft threat. By evening, flakes thickened into a steady curtain that painted eight inches across the prairie by dawn. Across the way, Carl Larson could be seen dragging armloads of wood from his shed, shoulders hunched, jaw clenched against the cold.

Tom Wagner’s chimney already poured a column of smoke thick enough to write its own opinion on the sky.

In the Meyer cabin, Elizabeth stepped barefoot across the floor for the first time since they’d arrived in Minnesota.

She stopped mid-step, startled.

“It’s warm,” she said.

Johan looked up from the table where he was sharpening a tool. “What is warm?”

“The floor,” she said, and a smile broke across her face like sunrise. “Johan… the floor is warm.”

The warmth didn’t roar. It didn’t demand attention. It didn’t fill the room with smoke and ash. It rose, steady and quiet, from below. It seeped into the pine planks. It made the cabin feel less like a box and more like shelter.

Johan walked across the room, bare feet on the boards, and felt it too. A gentle heat that made the blood in his toes remember how to move.

Below, the animals shifted and breathed, their bodies doing what bodies did: producing warmth as long as life remained inside them.

Johan had calculated it in his head a hundred times. Each animal, modest furnace in biological form. The thick stone walls, thermal mass that absorbed that heat during the day and released it slowly at night. The design was not magic.

But when you’re cold enough, physics feels like grace.

Elizabeth set their evening meal on the table. Their cooking fire was modest, a small flame compared to the roaring blazes visible through neighbors’ windows. She glanced out at Carl’s cabin, where light flickered frantic and bright.

“They burn so much wood,” she said, not criticizing, just measuring.

Johan nodded. “Carl must have cut twenty cords.”

“And we cut six,” she said.

“Six,” Johan agreed, “and we will use less than that if the winter is kind.”

Elizabeth raised an eyebrow. “Kind?”

He gave her a look that said he knew Minnesota had never heard the word.

December deepened. The differences between the Meyer place and the others grew sharp enough to cut pride.

Carl Larson could be seen at all hours, splitting kindling, banking fires, adjusting dampers, clearing ash. His wife Martha complained at church that her hands were cracked and bleeding from handling wood, and their cabin was either stifling hot near the stove or numbingly cold in the corners.

Tom Wagner’s children huddled close to the stove during the day and slept under piles of quilts at night. The family raced each morning to dress before the overnight chill sank into their bones.

Meanwhile, in Johan’s cabin, the children played on floors warm enough for bare feet. Elizabeth spun wool without gloves. The air stayed humid and fresh, warmed through the livestock quarters before rising, free of the acrid smoke that haunted most winter homes.

And for that comfort, the Meyers paid a social price.

At church, conversations paused when Johan approached. Eyes flicked to his boots, as if expecting to see manure. Women whispered and then smiled too brightly when Elizabeth turned.

Once, Martha Larson stood beside Elizabeth at the well, and though her voice was polite, suspicion sat in it like grit.

“Do you truly not smell them?” Martha asked. “All those animals?”

Elizabeth looked at her, then toward the white prairie where trees stood like thin black ribs against the sky.

“We smell them,” she said honestly. “The way we smell hay. The way we smell life.”

Martha’s mouth tightened. “And sickness?”

Elizabeth shook her head. “Our children have not coughed once.”

Martha didn’t answer. But her eyes lingered on Elizabeth’s hands, which were not cracked the way Martha’s were. They were busy hands, yes, but not ruined by firewood and desperation.

Jealousy is often just cold wearing a human face.

By Christmas, Carl Larson had burned through twelve cords of his supply and carried a persistent cough from smoke and ash. He grew irritable. Sleep-deprived. A man can be kind or cold, but it’s hard to be both at once.

In early January, the sky changed.

It wasn’t the gentle gray of snowfall. It was a hard, clean blue that looked almost cruel in its clarity. The temperature plunged to twenty-five below for three consecutive nights. Carl kept his fire so hot that the chinking in his cabin walls smoked and cracked. Tom Wagner climbed onto his roof during a blizzard to clear creosote buildup, cursing under his breath as snow drove into his face.

Then January 23rd arrived like a door kicked in.

Johan woke before dawn to a sound that made his bones listen: wind shaking the stones themselves, a howl that didn’t move around the cabin but through it. The storm outside turned the world into a white wall. Snow drove horizontally across the prairie. Earth and sky blurred into one furious thing.

The temperature dropped to thirty below when the storm began. By mid-morning it would reach forty below with wind that made the air feel like liquid ice.

This was the kind of cold that didn’t just hurt.

It negotiated for your life.

Johan moved quietly through the cabin, checking that the children were covered, that Elizabeth had warm tea, that the vent openings were adjusted properly. He went down to the livestock quarters with a lantern held close.

Below, the animals were calm. The thick stone walls muffled the storm until it sounded like a far-off ocean. The air held at around forty-two degrees, warmed by bodies and held by stone.

It felt almost… sheltered.

Johan ran a hand along the granite. “Good,” he murmured, like thanking an old friend.

When he returned upstairs, Elizabeth was seated at the table, needlework in hand, steady as if refusing to let panic turn the cabin into an enemy.

“Do you hear them?” she asked quietly.

Johan listened.

Through the storm’s roar came the faintest suggestion of labor: axes biting wood, frantic and uneven. The sound had the rhythm of fear.

The storm raged for three days and nights. Snow piled in drifts that reached the eaves of single-story buildings. The prairie became a blank page, and every homestead was a small, stubborn sentence written against erasure.

Inside the Meyer cabin, the temperature held steady near sixty. Johan burned less than half a cord of wood, mostly for cooking. Their chimney sent up thin wisps of smoke that looked almost embarrassed compared to the thick plumes rising from other cabins.

Across the way, Tom Wagner’s chimney glowed cherry red on the second night, visible even through driving snow.

Elizabeth stared out the small window, face tight.

“That isn’t right,” she whispered.

“No,” Johan agreed. “That is desperation.”

On the third day, the sounds outside changed. The steady rhythm of wood splitting became erratic. Smoke turned black. A sign of wet wood, of smoldering fires, of people burning what they never meant to burn.

Johan sat at the table, hands wrapped around a mug, and said the thing he’d been thinking since the storm began.

“When it breaks,” he told Elizabeth, “we go to them.”

Elizabeth looked up sharply. “Johan, they hate us.”

“They do not hate us,” he said. “They fear being wrong.”

“And if they refuse?”

Johan’s eyes softened. “Then we offer again.”

On the morning of January 26th, the storm broke. The silence afterward was so sudden it felt heavy. Johan stepped outside into a world transformed. Snowdrifts erased familiar landmarks. The air was clear, brutally cold, each breath like knives.

The temperature stabilized at twenty-eight below.

Johan’s first concern was not his own comfort. It was the dark quiet where other chimneys should have been.

Carl Larson’s chimney barely smoked.

Johan fought through waist-deep snow toward the Larson cabin. His eyelashes frosted. His lungs burned. When he reached the woodshed, he found Carl swinging an axe with the mechanical desperation of a man trying to split time itself into smaller pieces.

Carl didn’t look up at first. When he did, his eyes were bloodshot from smoke and sleeplessness.

“Johan,” he rasped, voice raw. “Thank God you made it through.”

Johan glanced at the woodpile. It was almost gone. A few pieces of green timber. Some half-burned scraps saved for reuse.

“What are you burning?” Johan asked.

Carl laughed once, bitter, then coughed hard enough to bend him over. “The children’s bed frame,” he said when he could breathe. “Martha’s inside trying to keep them warm. But the fire keeps dying no matter what we feed it.”

Johan stepped inside the Larson cabin and felt the cold claw at him. The air barely rose above freezing. The family huddled near the stove, wrapped in every quilt they owned. The children were listless, conserving energy.

Martha’s face was pale. She looked up at Johan like a woman staring at a rumor made real.

“It’s true,” she whispered, voice cracked. “Your house… is it really warm?”

Johan didn’t gloat. The frontier punished pride quickly, and he had no interest in borrowing trouble.

He simply said, “Yes.”

Tom Wagner’s situation was similar: fuel supplies low, chimney clogged with creosote, hands blistered from nonstop splitting. Tom’s wife Sarah looked like she’d aged a year in three days.

Johan stood between them outside afterward, snow squeaking under boots, breath turning instantly to crystals.

“Bring your families to my place,” he said, as practical as offering a shovel. “The cabin is warm enough for all of us. If your livestock need shelter, we can share the quarters.”

Carl’s jaw worked. Pride is a muscle too, and his had been exercised hard against Johan all season.

“I don’t know what to say,” Carl finally managed. “I… we mocked you.”

Johan nodded once. “Yes.”

Carl flinched, expecting condemnation.

Johan continued, “And now you need warmth. That is all.”

Tom Wagner swallowed. “Will… will it smell?” he asked, sounding ashamed that he still cared about such a thing when his children had nearly frozen.

Elizabeth, who had walked up behind Johan, answered. Her voice carried the firmness of a woman who had been whispered about for months and had not broken.

“It smells like hay and animals,” she said. “Like living. If that offends you, you’re welcome to stay cold.”

Sarah Wagner let out a small, surprised laugh that sounded like relief.

Tom bowed his head. “It won’t offend me,” he said quietly. “I just… want my children warm.”

The migration to the Meyer house-barn took most of the morning. Families loaded onto sleds. Children wrapped in buffalo robes stiff with frost. Women carried medicines, extra clothing, what food remained. Men led surviving livestock through deep snow, animals thin from burning calories just to stay alive.

When Martha Larson stepped into the Meyer cabin, she stopped just inside the door.

Warmth rose up through her boots as if the floor itself had decided to be kind.

Her eyes widened.

“It’s actually warm,” she breathed, as if naming a miracle.

The children shed coats. They moved. They laughed, uncertain at first, then full-throated, as if remembering they were allowed.

Sarah Wagner glanced around, expecting stale, smoky air. Instead, the cabin smelled of bread, wool, and a faint earthy sweetness.

“How is the air so fresh?” she asked Elizabeth, genuinely bewildered.

Johan answered, because this mattered. “The chimney draws air through the animals below. It warms it before it enters here. The stone holds heat. The animals provide it.”

Tom Wagner blinked, staring at the floorboards like they were telling secrets. “You built a… heater out of cows.”

Johan’s lips twitched again. “Yes,” he said. “A cow is patient. A stove is hungry.”

That first evening, packed with bodies and gratitude and bruised pride, Carl Larson sat on a bench near the table, hands wrapped around a mug of broth Elizabeth had pressed on him.

He stared at the room, at the children asleep in a cluster of blankets, cheeks pink instead of gray.

“I keep expecting to get cold,” he admitted quietly to Johan when the cabin settled into night. “In my place, you could feel the temperature dropping the moment the fire started to die. Here… it’s like the warmth stays.”

“It does,” Johan said. “Because the stone stores it. The animals make it. The building holds it.”

Carl swallowed. “I called it foolishness.”

Johan looked at him without hardness. “Many things look foolish until they save you.”

The next day, Tom asked to see the livestock quarters. Johan led him down the steps, lantern swinging. The warm hush below wrapped around them.

Tom breathed in, surprised. “It doesn’t smell bad,” he said.

Johan nodded. “Straw changed regularly. Drainage. Ventilation. The stone absorbs and dissipates.”

Tom watched the cattle chew contentedly, steam rising from their bodies.

“They’re warming us,” he said, awed, as if realizing the animals were not just property but partners.

“And they are healthier for it,” Johan added. “Cold barns steal weight. Warm barns keep it.”

Upstairs, Martha Larson helped Elizabeth with chores, her hands moving slower at first, then more confidently. She learned how Elizabeth managed bedding schedules, how she kept the lower level clean, how she used the warmth to dry clothes without wasting fuel.

Martha’s voice was softer when she spoke now. “I thought you’d be… dirty,” she confessed one afternoon, eyes lowered.

Elizabeth didn’t pretend it didn’t hurt. “And I thought you’d never look at me without disgust,” she answered.

Martha looked up. “I’m sorry.”

Elizabeth nodded once. “So am I. For believing you wanted me to suffer.”

They stood there a moment, the apology hanging in warm air like something fragile and real.

That cohabitation, meant to be temporary, stretched longer than planned because the storm had broken more than pride. It had broken fences, roofs, and in some cases, hope.

During those days, Johan explained what his grandfather had taught him, not as a lecture, but as survival shared.

Thermal mass. Heat storage. Ventilation. Low ceilings to reduce volume. Smaller windows to reduce loss. Orientation to catch sunlight when it came. He demonstrated how small choices created big differences, how comfort wasn’t always about more fuel, but about smarter shelter.

Carl listened like a man hearing Scripture for the first time.

“How much did the stonework cost you?” he asked.

Johan shrugged. “Time. Labor. Some money.”

“How long to build?” Carl pressed.

“Longer than a simple cabin,” Johan admitted.

Carl nodded, jaw tight, then said, “I burned eighteen cords of wood and nearly froze anyway.”

Johan didn’t reply. He didn’t need to. The truth was already sitting warm under their feet.

When the weather finally softened enough for the Larsons and Wagners to return, the leaving felt strange, like stepping out of a lesson too soon.

Martha stood at the door with Elizabeth, eyes shining. “You saved my children,” she said.

Elizabeth shook her head. “Johan saved them. And the cows,” she added, and Martha smiled through tears.

Carl Larson lingered last, hat in his hands, shoulders hunched as if expecting Johan to strike him with the words he deserved.

Instead, Johan held out his hand.

Carl stared at it, then grasped it hard.

“I was wrong,” Carl said, voice thick.

Johan’s grip was steady. “You were cold,” he corrected gently. “Cold makes people say foolish things.”

Carl laughed, hoarse but real. “You’re a better man than me.”

“No,” Johan said. “I am a man who remembers.”

Spring came slow, as if winter didn’t want to admit defeat. But when the snow finally melted into muddy rivers and prairie wildflowers pushed up like small celebrations, the story of the Meyer house-barn spread.

It spread the way useful stories always do: carried by tired men at supply runs, told by women at church gatherings, written in letters to relatives back east. The tale had a hook that even skeptics couldn’t ignore.

A Swiss immigrant built a cabin on top of a stone barn.

Neighbors laughed.

Then the worst blizzard in memory arrived.

And the one “foolish” house became refuge.

Carl Larson, once Johan’s loudest critic, became his loudest advocate. Pride, when it breaks, sometimes re-forms into something like courage.

“I called it foreign and unnatural,” Carl told a group of settlers one Sunday, voice ringing in the church hall. “But I’ll tell you what’s unnatural: burning your children’s bed frame to keep them alive. Johan used four cords of wood and kept three families warm. You can call it whatever you like. You cannot call it inefficient.”

Men began to ask questions. Not the mocking questions of autumn, but the hungry questions of people who had felt winter’s teeth.

How thick were the walls?

How did he vent the lower level?

How did he keep smells down?

How many animals were needed to heat a space?

Tom Wagner began sketching diagrams, measuring, recording details like a man trying to trap wisdom on paper before it ran away. He captured subtleties others would miss: the positioning of ventilation gaps, the chimney placement, the balance between fresh air and draft prevention.

Women asked Martha Larson about hygiene, about comfort, about whether the children slept well.

Martha answered with the honesty of someone who had been humbled into truth.

“The air was better than my own cabin,” she admitted. “No smoke. No ash. Warmth that didn’t come from panic.”

By summer, three new homesteads began construction with variations of Johan’s design. The Olsen family, late arrivals who had nearly frozen their first winter, invested in a stone foundation of their own. Others adapted the idea with partial basements, fewer animals, different materials.

Not every attempt succeeded. Some men tried to copy the structure without understanding the principles, building too thin, ventilating wrong, allowing drafts to steal warmth or moisture to create rot. The failures served as warnings: this wasn’t a gimmick. It was a system.

And systems demand respect.

Johan found himself traveling to neighboring settlements, advising on foundation design and ventilation. Letters arrived from Wisconsin and Iowa requesting details. His name, once spoken with laughter, was now spoken with a kind of practical reverence.

One evening in late summer, Johan stood outside his house-barn watching the prairie glow with sunset. Elizabeth came beside him, hands on her belly as if holding the quiet weight of their life.

“Do you ever think about that day?” she asked. “When they stood here and laughed?”

Johan considered. “Yes,” he said.

“And?” she prompted.

He looked toward the field where cattle grazed, slow and unbothered. “I think,” he said, “that laughter is easy when you haven’t been tested.”

Elizabeth leaned her head against his shoulder. “And when you have?”

“Then you learn what matters,” Johan said. “Warmth. Shelter. Sharing.”

She was quiet for a moment, then said softly, “You could have let them freeze.”

Johan’s voice lowered, serious now. “I could have,” he admitted. “And then I would have built a warm house on top of a cold heart.”

Elizabeth smiled, small and human. “That would have been the real unsanitary thing.”

Johan chuckled, and the sound was gentle.

Below them, animals shifted in the stone shadows. Above them, the cabin held the day’s remaining warmth like a secret kept for night.

The prairie would always be harsh. Winter would always return with its questions.

But now, the community had a new answer, built from old wisdom:

Sometimes the smartest heat is the kind you don’t have to chase.

Sometimes the best innovation is remembering what our grandparents already knew.

And sometimes, when the world is forty below and pride turns brittle as ice, the bravest thing a man can do is open his door and share his warmth with the very people who once laughed at his walls.

THE END

News

She Spoke Italian to Calm a Lost Child — Mafia Boss Froze and Ordered: “Find Everything About Her”

The boy stood in the middle of the walkway like a dropped stitch in a beautiful sweater. Millennium Park glittered…

Single Mom Got Fired for Being Late After Helping an Injured Man — He was the Billionaire Boss

The wind off Lake Michigan had teeth that morning, the kind that slid under coats and found the soft places…

Little Girl Called Her Veteran Father and Said, “Daddy, My Back Hurts” — Until He Came Home and Saw…

The call came the way disasters often do: small, ordinary, almost polite. Jack Hollis had been standing in a gravel…

Everyone Feared The Mafia Boss’s Fiancée — Until The New Maid Changed Everything, Shocking Everyone

The Grand Hall of Cedarcrest Manor didn’t fall silent because the string quartet paused or because a glass shattered. It…

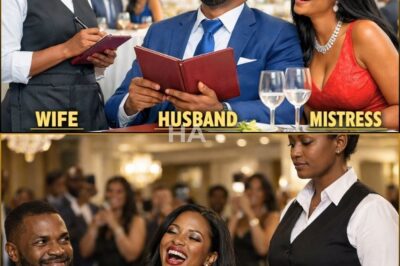

Husband Orders Food In A Foreign Language To Humiliate His Wife — Her Reply Silenced The Room

The chandelier above the Grand Willow Hotel restaurant was the kind that made people sit up straighter without realizing it….

Arrogant Husband Slapped Pregnant Wife At Family Dinner And Kicked Her Out Into The Snow While His..

The first thing that broke was the champagne glass. It leapt from Rebecca Harrison’s fingers when Tyler’s palm cracked across…

End of content

No more pages to load