The Boy Behind the Velvet Curtain

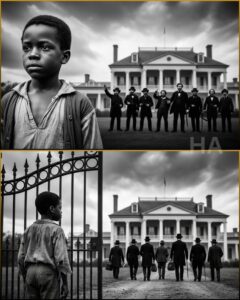

The first time Isaiah realized the city of Natchez ran on two different kinds of light, he was nine years old and standing perfectly still.

Upstairs, in the Devereux dining room, candle flames trembled inside crystal sconces and turned every glass into a small, private sun. Laughter bounced off plaster walls painted the color of cream. Silverware chimed like money.

Downstairs, in the kitchen, the light was greasy and practical. It came from the hearth and from the open mouth of an oven. It clung to cast iron and sweat. It made faces look older than they were.

Isaiah lived in the space between those two lights.

He did not belong to the Devereux family, but the Devereux family would have said he did, the way a man might say he owned a chair or a horse. He belonged to the plantation outside town that supplied labor to Natchez’s most respectable households, a “lending” operation dressed up in polite language so everyone could keep their hands clean.

When Isaiah carried a tray into the dining room, nobody asked his name. When he stood behind velvet curtains holding a decanter, nobody worried what he heard. They talked with the unguarded ease of people who believed they were the only people in the world.

That night, Colonel Fitz Devereux raised his glass to the new cotton contract, to the riverboats, to the men who knew how to turn land into gold. Around him sat lawyers, merchants, judges, and a preacher who smiled the way a man smiles when he thinks God is firmly on his side.

Isaiah’s job was to pour when the glasses lowered. To collect when the plates emptied. To move so quietly the room forgot it had been served at all.

He poured bourbon into a glass held by a man with soft hands and sharp eyes, Mr. Larkin, who wrote contracts for a living and spoke like every sentence belonged on a courthouse wall. He poured again, and again, and by the third refill Mr. Larkin leaned toward the colonel and lowered his voice.

Not low enough.

“About your debts,” Mr. Larkin said, in the gentle tone men used when they wanted cruelty to sound like help. “You can settle them quick enough if you let me handle the sale.”

Colonel Devereux grunted. “I’m not selling my land.”

“Not the land,” Mr. Larkin replied. “The… excess.”

A laugh moved around the table, not loud, not wicked, just casual. Comfortable. Like a man stepping into his own bed.

Isaiah stared at the rug. He could feel his own heartbeat in his throat. He’d learned young that eyes were dangerous. If you looked too long, you were accused of thinking. If you looked away too fast, you were accused of hiding.

Mr. Larkin’s ring tapped his glass. “A lot of buyers downriver,” he continued. “Louisiana, Texas. They pay more for the young ones. Strong backs. Quick hands.”

The colonel took a slow sip. “My wife will complain.”

“She’ll complain no matter what you do,” Mr. Larkin said with a chuckle. “But she’ll stop complaining when the house stays standing.”

Across the table, a woman with pearls at her throat smiled, then frowned as if she’d tasted something sour. “It isn’t decent,” she murmured. “Not to sell families apart.”

Mr. Larkin shrugged. “Decency doesn’t pay interest.”

Isaiah felt heat crawl up his spine. Not rage, not yet. Something colder. Something that sat down inside him like a stone and refused to move.

Because he understood what “the young ones” meant.

He understood what “excess” meant.

He understood that the colonel’s debt had a name in the quarters, and that name was Mercy.

Mercy was Isaiah’s little sister.

She was seven and small and bright in a way the overseer hated, always humming when she worked, always staring at birds like she believed they might speak back. The week before, Mercy had slipped Isaiah a rag doll she’d made from old cloth, its face stitched with careful patience. “So you won’t be lonely in town,” she’d whispered.

Isaiah had hidden it under his straw mattress like it was a secret hymn.

Now, upstairs, men laughed softly while deciding whether Mercy would be shipped south like a crate of nails.

He carried the tray back out, his arms steady, his face empty. The skill of emptiness had been trained into him the way a blacksmith trains iron, heat and hammer until the metal learns what shape it is allowed to be.

But emptiness, Isaiah would learn, has room inside it.

Room for memory.

Room for counting.

Room for waiting.

In Natchez, everybody knew everybody, or at least they knew each other’s houses.

The city sat on a bluff above the Mississippi River, watching the water drag the country’s wealth past its feet. By 1856, Natchez had grown fat on cotton and pride. The grand homes wore their columns like crowns. Gardens bloomed as if the soil itself had been bribed.

People came from miles around to admire the architecture, the parties, the carriage lines on Sundays. They praised refinement. They praised Christian virtue. They praised a kind of gentility that needed invisible labor the way a body needs blood.

Inside those homes, the aristocrats competed through lace and chandeliers and the length of their guest lists. Their wives hosted teas with imported sugar. Their husbands spoke of politics with the certainty of men who had never been told no.

And through all of it moved the servants.

Enslaved cooks. Enslaved housekeepers. Enslaved drivers. Enslaved boys carrying trays.

The city treated them like fixtures, like doors and rugs. People blamed a rug when they tripped. People praised a door when it shut quietly. Nobody asked what either one wanted.

Isaiah was loaned out because he was “good in the house.” He wasn’t large enough yet for the fields, and the plantation’s owner liked the small profit of renting him to Natchez families who wanted an errand runner, a quiet helper, a child whose silence felt reassuring.

So Isaiah crossed thresholds for a living.

He learned which families ate late and which ate early. Which houses locked their pantries and which relied on habit as security. Which women demanded special teas for “the nerves.” Which men kept tonics in their desk drawers and called them medicine.

He learned the language of wealth, not from books, but from overheard arguments. He heard men fight over debts, over land, over which cousin would inherit what. He watched papers burn in fireplaces. He watched hands tremble when they signed.

And he learned something else, something the aristocrats never thought they were teaching.

He learned that their power was not a fortress.

It was a performance.

A performance held together by routine and denial.

If the routine cracked, if denial failed, the whole grand show could collapse like a stage set.

He did not decide to become dangerous overnight.

Danger is rarely born in a single flash. It is assembled.

Isaiah assembled his in tiny pieces: an insult here, a slap there, a scream from the quarters that nobody upstairs acknowledged. A Sunday sermon about obedience while a man’s back still bled under his shirt. A mistress pretending not to see the bruises on the cook’s arms.

And then, that night at the Devereux table, Mercy’s name entered the conversation without being spoken.

Isaiah went back downstairs and stood near the kitchen doorway, watching Auntie Ruth stir a pot with the steady patience of someone who had learned to endure time itself.

Auntie Ruth was not his aunt by blood. In the quarters, “auntie” was what you called a woman who had survived long enough to become a pillar. She’d raised other people’s children because their mothers had been sold or buried or broken.

She looked at Isaiah’s face and paused. “What you hear up there?” she asked softly, as if the walls might eavesdrop.

Isaiah hesitated. He wanted to say nothing. Silence was safer.

But Auntie Ruth’s eyes were not the soft blindness of the dining room. Her eyes carried the sharpness of someone who had always been forced to notice.

“They talkin’ downriver,” Isaiah whispered.

Auntie Ruth’s spoon stopped. For a moment, her hands did not move at all, as if her body itself needed time to decide whether it could keep functioning.

“Who?” she asked.

Isaiah swallowed. “Mercy.”

The kitchen’s heat suddenly felt like winter. Auntie Ruth stared at him, then turned back to the pot and stirred so hard the broth sloshed.

“Child,” she said, voice rough, “don’t you go doin’ nothin’ foolish.”

Isaiah didn’t answer. He didn’t know how to explain that foolishness was what the world called any action an enslaved person took to protect their own.

He went out into the yard behind the house, where the night smelled like magnolias and damp soil. He looked up at the second-floor windows glowing with candlelight and laughter.

He thought of Mercy’s rag doll.

He thought of Mr. Larkin’s ring tapping the glass.

He thought, with a clarity that frightened him, that the men upstairs lived as though consequences were something that happened to other people.

He felt the stone inside him settle deeper, heavier.

And then, in the dark behind the house, Isaiah began to count.

When the first man died, the city treated it like an inconvenience.

Colonel Devereux hosted a spring banquet a week later, because Natchez did not cancel celebration for something as common as death. A respected planter from upriver attended, a man known for his wide smile and his habit of pinching servant boys’ ears as if they were pets.

He ate too much, drank too much, and complained about his stomach before retiring.

By morning, he was dead.

The doctor said apoplexy. The preacher said it was God’s timing. The widow said she couldn’t bear to stay in the house. The men at the funeral nodded solemnly and calculated what the death meant for land deals and contracts.

Isaiah stood at the edge of the gravesite holding flowers for the mistress, eyes down, expression blank. He listened to men speak of the dead as though his absence from the world had created a vacancy in the marketplace.

Nobody watched Isaiah. A boy at a funeral was part of the scenery.

Two weeks later, Mr. Larkin collapsed after supper in a different house, a friend’s place near the bluff. He complained of heat in his chest, of a strange bitterness in his mouth. He tried to stand. He fell. He died before the physician arrived.

That time, the death felt less like coincidence.

Mr. Larkin had been young enough to seem sturdy. He had enemies, yes, but no one imagined enemies could reach into a dining room and touch a man surrounded by silver and servants.

People whispered about bad oysters. About tainted whiskey. About the river bringing sickness.

Natchez moved on, because Natchez always moved on. The city’s rhythm depended on forward motion. Stopping meant looking too closely.

But the deaths did not stop.

A judge died in his study after a late-night brandy. A merchant died in his sleep. A plantation mistress grew pale after tea and never rose from her bed.

Each death came quietly, politely, almost in keeping with the city’s manners. No knives. No gunshots. No dramatic struggle that would force a clear villain.

Just absence.

Just chairs at tables left empty.

And because there was no obvious violence, the aristocrats treated the deaths like a puzzle, not a threat. They debated causes the way they debated crops, like men discussing weather patterns.

Only the doctors began to look afraid.

Dr. Thomas Hale was twenty-six and new to Natchez, a physician with careful hands and a conscience that had not yet learned how to sleep through screams. He’d come south for opportunity, telling himself he could practice medicine without touching the institution that made the city rich. He’d told himself a man could live inside a rotten house without becoming part of the rot.

By midsummer, after the eighth funeral, Dr. Hale stopped telling himself comforting lies.

He sat in his small office behind the apothecary, papers spread across his desk, comparing notes he was not supposed to compare. Names. Dates. Symptoms. Houses.

A pattern emerged with the slow certainty of dawn.

These people were connected, not by blood, but by dinners.

By social circles.

By shared staff.

In Natchez, enslaved labor moved between households like wind. A cook might spend a week at the Devereux home, then a month at the Larkins’, then be sent to help at a wedding across town. The city’s elite did not truly live as separate families. They lived as a single organism, connected through servants and commerce and constant visiting.

If something was wrong, it was wrong inside the organism.

Dr. Hale stared at the list until his eyes burned. The thought he was circling felt impossible, and yet it would not go away.

If the danger was inside the houses, then it could only come from one place.

The kitchens.

The idea turned his stomach, not because he believed enslaved people incapable of intention, but because he understood what the city would do if he said it aloud. Natchez did not investigate downward. Natchez punished downward.

And when fear rises in an empire, the first victims are always the ones who can’t fight back.

Dr. Hale did not know Isaiah’s name, not yet. He only knew there was often a small boy present when he was called to the homes of the dying, a boy who moved like a shadow with a pitcher of water, a boy whose eyes were always lowered, as if the floor were the only safe place to look.

Dr. Hale had barely registered him.

Which, Isaiah would have said, was the point.

When suspicion finally arrived, it arrived wearing gloves.

At church, aristocrats smiled through hymns and watched each other’s hands. At teas, women spoke of weather and quietly pushed untouched cakes away from their plates. Men began drinking from bottles kept in their own pockets instead of trusting what a host poured.

They dismissed servants for small mistakes. They locked pantries. They reduced menus as if simpler food might be safer food.

And then, one hot afternoon, the panic chose its first scapegoat.

Auntie Ruth was dragged into a courtyard behind the Harrowgate house, accused by a trembling mistress whose brother had died two nights earlier. The accusation was not evidence. It was desperation.

“She puts strange things in the soup,” the mistress said, voice high and frantic. “She’s always muttering. I saw her with herbs.”

Herbs. As if seasoning were sorcery. As if cooking itself were a crime.

A crowd gathered, mostly white faces, a few enslaved men standing stiffly at the edges, eyes fixed on the ground. Nobody moved to defend Auntie Ruth because defense was dangerous. The world had taught them that courage could get your children sold.

Auntie Ruth stood straight, shoulders square, hands bound. Her face was calm in the way of someone who has been calm through horrors and knows panic won’t save her.

Isaiah watched from behind a wagon, his stomach hollow.

This was not what he wanted, a voice inside him whispered.

And another voice, colder, replied: This is what always happens.

Dr. Hale arrived because someone had called for a doctor as if medicine could solve fear.

He saw Auntie Ruth’s wrists raw from rope. He saw the mistress’s flushed cheeks, her shaking hands. He saw two men with whips, eager for permission to turn suspicion into spectacle.

And he saw, behind the wagon, a boy’s face half in shadow.

Isaiah’s eyes met his, just for a second.

There was no begging in them.

There was something else, something that made Dr. Hale’s breath catch. A stillness that did not feel like resignation. A stillness that felt like calculation.

Dr. Hale raised his voice, forcing it to sound firm. “If you beat her,” he said, “you will learn nothing except how to become savages in front of your own children.”

A murmur moved through the crowd. Offense flared. Dr. Hale knew he’d crossed a line. In Natchez, you could do almost anything to enslaved people. You could not call white men barbaric out loud.

A planter stepped forward, face tight. “Doctor,” he said, “we are trying to protect our families.”

Dr. Hale looked at Auntie Ruth. Then he looked at the crowd. “Then protect them with reason,” he replied. “If you want answers, you investigate. You don’t flail.”

The men with whips hesitated, not out of mercy, but because Dr. Hale was white and carried the authority of education. They did not respect Auntie Ruth’s humanity, but they respected the idea of a gentleman.

The mistress burst into tears. “Then what do we do?” she cried. “People keep dying.”

Dr. Hale felt the truth press against his teeth. He could taste the danger of speaking. If he said the kitchens might be involved, they would tear those kitchens apart and call it justice.

He chose a lie, a smaller lie than the city’s usual lies. “We look at the medicine,” he said. “The tonics. The imported powders. We start there.”

It was not the whole truth, but it was a direction that might buy time.

And time, Isaiah knew, was the only thing that ever changed anything.

That night, Isaiah sat on the floor of the slave quarters with Mercy’s rag doll in his lap and listened to the adult whispers around him. People talked about Auntie Ruth, about blame, about fear. People talked about downriver sales as if the words themselves could summon chains.

Mercy slept beside him, her breath warm against his arm.

Isaiah’s stone grew heavier.

He understood then that if he did nothing, the city would still kill.

It would kill quietly, through sales and separation and punishment disguised as law.

If he acted, the city would kill loudly, in anger, trying to restore the illusion of control.

He did not see a path without blood.

But he did see one difference.

If he acted carefully, he might save Mercy.

He might save a few others.

Not with heroics. Not with speeches. With something Natchez could not defend against because it refused to see it coming.

He leaned his head back against the wall, closed his eyes, and chose patience again.

By late autumn, Natchez felt haunted.

Houses sat dark behind iron gates. Carriages rolled less often down the main streets. Women stopped hosting, stopped inviting, stopped trusting. The city’s social calendar, once as reliable as sunrise, began to tear like old cloth.

And with each tear came new kinds of ruin.

When powerful men died, their estates did not simply pass neatly to heirs. Debt crawled out of desks and ledgers like insects, suddenly visible. Wills were contested. Business partnerships collapsed. Credit dried up.

One death was grief. Ten deaths were a crisis. Dozens became an earthquake.

Natchez’s aristocracy had always believed itself untouchable because it believed it owned the world. But ownership is not the same as stability. The more the city tried to tighten its grip, the more it realized its fingers were shaking.

Isaiah moved through it all with a tray in his hands.

He was assigned to more houses, not fewer, because familiarity became a fetish. Families believed that servants they “knew” were safer than new ones, as if a human being could be made harmless by recognition.

They requested Isaiah because he was quiet. Because he never argued. Because he did not meet their eyes.

Because he did not look like a threat.

In truth, Isaiah was not one thing. He was several things at once: a child forced to grow up too fast, a witness trained by cruelty, a mind sharpened by listening.

And somewhere inside him, under the stone, there was still a small, stubborn spark of wanting to live in a world where Mercy could hum without fear.

Dr. Hale’s investigations had led him to apothecaries, to shipments, to medicine cabinets, and he kept finding the same answer: confusion. Nothing consistent enough to explain what was happening.

What remained consistent were the dinners.

The shared meals.

The invisible hands.

And the boy.

Dr. Hale began to notice Isaiah the way you begin to notice a word repeated too often in a book, a word you’d skimmed over until it started to glow.

He saw Isaiah at the Devereux home one week, then at Harrowgate the next. He saw him carrying water at a sickbed, then serving at a funeral. He saw him in a hallway when men whispered about “witchcraft” and “poison” and then, without thinking, continued the conversation as if Isaiah were wallpaper.

One evening, after a long day of calls, Dr. Hale found Isaiah alone in a back passage behind the Larkin house, holding a basket of linens. The boy stood still, waiting for permission to move.

Dr. Hale looked at him, truly looked, and felt a strange shame.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

Isaiah’s eyes flickered up, then down. “Isaiah,” he said softly, as if the name might be taken away if he spoke it too boldly.

Dr. Hale nodded, heart tightening. “How old are you?”

“Thirteen,” Isaiah replied.

Thirteen. Dr. Hale imagined his own little brother at thirteen, running through fields, arguing about books, complaining about chores. He looked back at Isaiah’s thin arms, the careful stillness, the way his body seemed trained to disappear.

Dr. Hale lowered his voice. “Isaiah,” he said, “have you seen anything… unusual?”

Isaiah did not answer. Not because he didn’t understand, but because he did.

If a doctor was asking questions, the world was turning. When worlds turn, children get crushed.

Dr. Hale watched the boy’s face, searching for fear, for guilt, for something he could name.

Isaiah’s expression remained calm.

And then, unexpectedly, Isaiah spoke.

“Do you think,” he asked, voice quiet as dust, “a man can do evil and still sleep easy?”

The question struck Dr. Hale like a slap.

He tried to respond with philosophy, with scripture, with all the comfortable abstractions educated men used to keep reality at arm’s length.

But Isaiah’s eyes lifted again, and Dr. Hale saw it: not accusation, exactly. Something worse.

Expectation.

As if Isaiah already knew what kind of man Dr. Hale would choose to be.

Dr. Hale swallowed. “No,” he said finally. “Not forever.”

Isaiah nodded once, as if confirming a calculation. Then he stepped past Dr. Hale and disappeared into the house with the basket, leaving Dr. Hale alone with the feeling that he’d just been examined, not the examiner.

That night, Dr. Hale couldn’t sleep. He lay in the dark listening to the city’s silence and thinking of Isaiah’s question.

Because it wasn’t only the aristocrats who did evil.

It was everyone who benefited from it and called it normal.

The turning point came not with a death, but with a letter.

Amelia Devereux, the colonel’s wife, had always been praised for her composure. In Natchez society, composure was currency. She held her chin high at funerals, hosted teas even when her hands trembled, and smiled through terror because a trembling smile was still a kind of armor.

But by November, after yet another burial, Amelia began to crack.

It happened late one afternoon when she found a small folded paper tucked beneath the silver tray Isaiah had carried out of the dining room. It was not addressed. It was not sealed. It was simply there, like a dare.

She hesitated before opening it. Her fingers shook, not with frailty, but with a sudden anger at the world for making her afraid of paper.

Inside, written in careful, plain script, were four sentences.

You speak of decency as if decency is a dress you wear to church.

You do not ask what it costs.

The cost is paid in kitchens.

The kitchen keeps receipts.

Amelia stared at the words until her throat tightened. A chill traveled over her skin.

She read it again, then again, as if repetition might make the meaning less sharp.

It did not.

She thought of her husband’s debts. Of Mr. Larkin’s smile. Of the way she’d looked away when a servant girl limped past with swollen eyes. Of how she’d told herself she had no power, no choice, as if being a woman in Natchez excused being complicit.

The letter felt like a hand reaching through the wall and touching her heart.

She did not know who had written it.

But she knew who had placed it.

Isaiah had served her tea that morning. Isaiah had carried the tray.

A boy no one noticed.

A boy who had just reminded her that invisibility could be intentional.

Amelia did something she’d never done before.

She went downstairs into the kitchen.

Auntie Ruth was chopping vegetables, her hands moving fast, her face expressionless. The other servants froze when Amelia entered, startled by the sight of a mistress in a space she usually ignored.

Amelia held the note in her hand. “Who wrote this?” she demanded, voice trembling.

Silence fell heavy.

Auntie Ruth looked up slowly. Her eyes flicked to the paper, then to Amelia’s face. “I don’t know,” she said.

Amelia’s gaze darted around the room. Isaiah was not there.

Of course he wasn’t.

She clutched the paper so hard it crumpled. “People are dying,” she whispered, as if speaking softer might keep her from sounding hysterical. “We are frightened. And you… you write riddles?”

Auntie Ruth’s jaw tightened. “We been frightened,” she said quietly, and there was no riddle in it at all. “We been dyin’.”

Amelia flinched as if struck, because truth spoken plainly has a violence of its own.

She backed out of the kitchen with her composure in tatters.

Upstairs, she found her husband in his study, staring at ledgers like a man trying to wrestle numbers into obedience. She threw the crumpled note onto his desk.

He read it, his face darkening. “This is insolence,” he snapped.

“This is a warning,” Amelia replied, surprising herself with the steadiness of her own voice. “We have built a world that hates us, Fitz. And we pretend not to notice because it’s inconvenient.”

Colonel Devereux slammed his fist on the desk. “Watch your tongue.”

Amelia leaned in. “Watch your house,” she said. “Watch the people you pretend are furniture. They are not.”

For a moment, the colonel’s eyes widened, not with fear, but with outrage that his wife had spoken like a person with opinions. Then his face hardened into the old familiar mask.

“I will not be threatened by a child,” he said.

Amelia stared at him and realized, with a sudden bleak clarity, that her husband’s denial was not ignorance.

It was devotion.

He was devoted to the lie that kept him powerful.

And devotion, she understood, could be lethal.

Two nights later, Natchez’s most prominent families gathered at the Harrowgate mansion for what was supposed to be a “private reassurance.” A meeting of the city’s pillars, away from gossiping neighbors, to discuss safety measures and present a united front.

If Natchez looked weak, it would invite outside vultures.

If Natchez admitted vulnerability, it would admit something worse.

That it had never truly been in control.

Dr. Hale was invited because aristocrats trusted medicine the way they trusted locks: as a tool that made them feel less mortal.

Amelia attended because her husband insisted, and because she wanted to watch the room. She wanted to see how denial looked on other faces.

Isaiah attended because Isaiah was always where the food was.

He moved among the guests with a tray of glasses, his body a practiced silence. The room smelled of cologne and roasted meat and panic disguised as politeness.

Men spoke in low tones. Women smiled too brightly. A few glanced at servants with narrowed eyes, like people studying shadows for fangs.

Dr. Hale stood near the fireplace, listening as a judge suggested dismissing half the household staff and importing “new, reliable servants” from farther south. Another man proposed locking the kitchens at night, as if chains worked differently on a door than on a person.

Amelia watched Isaiah glide past and felt her skin prickle. The boy’s face remained blank, but his presence felt suddenly electric to her, as if she’d finally noticed a wire running through the walls.

When the host called for attention, the room quieted.

“We are being tested,” Mr. Harrowgate said, voice thick with self-importance. “By illness, by fate, perhaps even by wickedness. But we are Natchez. We will endure.”

A murmur of agreement, thin and shaky.

Dr. Hale cleared his throat. He hadn’t intended to speak. He’d promised himself he would observe, not provoke. But Isaiah’s question echoed in his mind like a bell: Do you think a man can do evil and still sleep easy?

Dr. Hale stepped forward. “If you want to endure,” he said, “you must stop chasing comfortable explanations. Something is happening in this city that requires honesty.”

A few faces stiffened. Honesty was not a popular guest in Natchez.

Dr. Hale continued, choosing each word like a man walking through a room full of loaded guns. “The pattern suggests a common element. Shared gatherings. Shared meals. Shared staff.”

The room went still. A woman’s fan stopped mid-flutter.

Someone scoffed. “Are you accusing our servants?” a planter asked, offended on behalf of his own pride.

Dr. Hale felt sweat form under his collar. “I am accusing no one,” he said, though he knew the sentence was already a kind of accusation. “I am saying the kitchens can no longer be treated as invisible. You cannot demand trust without examining what you have built trust upon.”

A judge’s eyes narrowed. “So what do you propose, Doctor?”

Dr. Hale opened his mouth, and before he could answer, a soft voice spoke from behind him.

Not loud. Not dramatic. Just present.

“I propose,” Isaiah said, “you read what you already know.”

Every head turned.

The room seemed to hesitate, as if it couldn’t quite process a servant boy speaking without permission. Isaiah stepped forward from the shadow of a curtain, holding something small in his hand.

A folded paper.

Amelia’s stomach dropped. She recognized the careful script.

Isaiah held the paper out toward Dr. Hale. The gesture was simple. It was also, in that room, revolutionary.

Dr. Hale stared at Isaiah, seeing the boy fully for the first time: the thin shoulders, the calm face, the eyes that carried an older kind of grief.

“What is that?” Dr. Hale whispered.

Isaiah’s voice remained steady. “Receipts,” he said.

Dr. Hale took the paper with shaking fingers and unfolded it.

Inside was a list of names.

Fifty-six names.

Some were already dead.

Some sat in that very room.

Beside each name was not a confession of poisoning or a dramatic declaration of revenge. It was something more devastating.

Details.

A hidden debt. A forged signature. A land theft. A woman’s “accident” that wasn’t an accident. An enslaved child sold to cover gambling losses. A beating disguised as discipline. A man’s Sunday prayer paired with his Monday cruelty.

The room inhaled as one organism.

Dr. Hale lifted the paper, and his voice came out rough, not with anger, but with the sudden weight of truth. “You have spent your lives believing the kitchen forgets,” he said. “Believing the people you starve of names cannot keep records. But you built your comfort on their silence, and silence, it turns out, can count.”

Isaiah stood beside him, small and unflinching, and the unforgettable line landed in the room like a verdict: “You called me furniture, so I learned to rearrange the house.”

Chaos erupted, not with screams first, but with denial. Men shouted. Women cried. Someone tried to snatch the paper. Someone accused Dr. Hale of hysteria. Someone lunged toward Isaiah, face twisted with fury at the audacity of being seen.

A guard grabbed Isaiah’s arm.

Amelia moved without thinking. She stepped between Isaiah and the man, her own body shaking, her voice sharp as broken glass. “Don’t touch him,” she snapped.

Her husband stared at her like he’d never met her.

Isaiah looked at Amelia, and for a moment, something flickered in his eyes. Not gratitude exactly. Recognition. Like he’d marked her as a person who might still have a soul.

Mr. Harrowgate demanded the paper be burned. A judge demanded Isaiah be whipped until he confessed to everything. Several men demanded servants be rounded up and “questioned.”

Dr. Hale held the list against his chest as if it were a living thing. He suddenly understood the trap Isaiah had set.

The deaths, the fear, the unraveling of routine, all of it had forced the aristocracy into the same room, desperate to restore order.

And now Isaiah had handed them what they feared more than death.

Evidence of themselves.

Their own rot, written down.

Because a scandal could ruin a legacy in ways a coffin could not.

Because a list could do what whispers could not: make denial impossible.

Natchez’s elite did what elite societies always do when confronted with their own reflection.

They tried to shatter the mirror.

The following weeks did not bring peace.

They brought collapse.

Some men fled the city with their families, abandoning estates before the river could carry the rumors farther. Some men locked themselves in their homes and refused food prepared by anyone but their wives, only to discover their wives did not know how to keep a household alive without the people they’d enslaved.

Partnerships dissolved. Credit vanished. Lawyers turned on clients to save themselves. Church elders argued behind closed doors about whether scandal counted as sin if it was never spoken aloud.

The list did not stay in one hand.

Dr. Hale, shaken and furious, copied it. He gave one copy to Amelia, who hid it beneath floorboards in her bedroom like a criminal hiding contraband. Another copy found its way into the hands of a rival merchant who had been waiting years to topple certain families. Another copy, in time, traveled north on a riverboat tucked inside a book of sermons, because nothing carried secrets better than holiness.

The deaths continued, though more sporadically now, as if the city itself had grown exhausted.

But the greater destruction was social.

Natchez’s aristocracy was not undone by a single culprit dragged into court. It was undone by the unraveling of trust.

Once you suspect the man at your table is lying about his debts, you stop lending him money.

Once you suspect the preacher’s piety is performance, you stop letting him bless your deals.

Once you suspect your wealth rests on crimes someone has written down, you start watching every shadow for paper.

In that climate, fifty-six names did not need to die to fall.

They only needed to be exposed, frightened, and turned against each other.

And Isaiah?

Isaiah vanished.

It happened the way his life had happened, through spaces people did not watch.

One morning, Dr. Hale arrived at the Devereux house to treat the colonel’s shaking hands. The colonel’s face was gray, his eyes bloodshot from sleeplessness. He gripped his desk as if wood could anchor him.

“Someone took the boy,” the colonel rasped, as if reporting a missing chair.

Amelia stood by the window, pale but steady. Her eyes met Dr. Hale’s, and in them he saw a complicated storm: fear, guilt, something like relief.

“Who?” Dr. Hale asked.

Amelia’s voice was quiet. “No one took him,” she said. “He left.”

The colonel spun toward her. “He can’t leave,” he snapped. “He belongs to us.”

Amelia’s smile was small and terrible. “That,” she replied, “is the first lie that broke.”

Dr. Hale’s heart pounded. “Where is Mercy?” he asked suddenly, remembering the name Isaiah had never spoken to him but that now seemed to hang in the air of everything.

Amelia hesitated, then answered with careful precision. “Safe,” she said. “For now.”

Dr. Hale understood then that Isaiah’s plan had never been only destruction.

It had been cover.

Fear and scandal created openings.

In openings, people could slip through.

Isaiah had learned to move through houses unseen. It made sense he’d use the same skill to move out of the city’s story.

Still, escape was not a clean ending. In the South of 1856, freedom was not a door you walked through and closed behind you. It was a chase. It was a hunger. It was a constant risk of being caught and made into an example.

Dr. Hale did not know if Isaiah would survive.

He did know that the boy had forced Natchez to feel, briefly, what enslaved people lived with daily.

Uncertainty.

Vulnerability.

The terror of not knowing what tomorrow would do to your body.

Years later, after war ripped the country open and the word “emancipation” became law instead of rumor, Dr. Hale returned to Natchez as a different man.

The city still had its grand homes, restored and admired. Tour guides spoke of architecture and elegance, of “a bygone era,” as if bygone meant forgiven. People preferred stories that made them feel proud.

But Dr. Hale walked past kitchens and heard ghosts.

He opened a small clinic on the edge of town where freed families could come without being turned away. He treated fevers, broken bones, childbirth, and the deep invisible injuries that came from surviving a system designed to erase you.

Sometimes, late at night, he thought of Isaiah’s list.

Not the names alone, but the idea behind it.

Receipts.

Proof that the kitchen had always been awake.

One afternoon, a young woman came to the clinic with a little boy clinging to her skirt. The woman’s name was Mercy.

Dr. Hale recognized it like a bell in his chest.

She was older now, her posture wary, her eyes sharp. When Dr. Hale said her name softly, she studied him as if deciding whether he was safe.

“I knew a boy named Isaiah,” Dr. Hale said, voice careful. “Once.”

Mercy’s expression did not change much, but something in her gaze softened by a fraction. “Lots of folks knew him,” she replied.

“Do you know what happened to him?” Dr. Hale asked.

Mercy looked down at her child, then back up. “History don’t write down everything,” she said. “Some things stay alive because they don’t get written.”

Dr. Hale swallowed. “Was he… was he a monster?” he asked, because the question had haunted him for years.

Mercy’s eyes narrowed slightly, not with anger, but with tiredness. “He was a boy,” she said. “And the world made him choose between being swallowed and biting back.”

Dr. Hale nodded, feeling the truth settle in him with the same heaviness Isaiah had carried.

Mercy shifted her son higher on her hip. Before she left, she said, almost casually, “He told me to keep humming. Said that was how you remember you’re still human.”

Then she walked out into the sunlight, her child’s small hand gripping hers, and Dr. Hale stood in the doorway watching them go, realizing the humane ending he’d been desperate for was not a clean redemption.

It was simply this:

A child who had been treated as invisible had forced an entire city to notice, if only for a moment, that the people in the kitchen were people.

And some of those people had lived long enough to walk free.

Natchez never fully recovered its old certainty. Maybe no society does, once it learns the truth about its own blind spots. The city learned, the hardest way, that power maintained through denial becomes brittle.

Because the darkest secret of Natchez was not only what happened in 1856.

It was that it could happen at all, simply because a child had been trained his whole life to disappear.

And then, one day, he decided not to.

THE END

News

A Billionaire Stopped at a Broken Diner and Saw a Waitress Feeding a Disabled Old Man — What He Learned That Night Changed Everything He Thought He Knew About Power

The rain that night did not fall gently. It came down with purpose, thick sheets that slapped the windshield and…

A Singgle Dad Lost Everything — Until the Billionaire Came Back and Said, “You’re With Me”

Rain made everything in Chicago look honest. It flattened the skyline into a watercolor smear. It turned streetlights into trembling…

I came home after an 18-our shift and found my daughter sleeping. After a few hours, I tried to wake her up, but she wasn’t responding. I confronted my mother and she said …..

The fluorescent lights of St. Mary’s General always buzzed like trapped insects. I’d heard that sound for nearly a decade,…

He arrived at the trial with his lover… but was stunned when the judge said: “It all belongs to her”.…

The silence in Courtroom 4B was so complete that the fluorescent lights sounded alive, a thin electric buzzing that made…

He ruthlessly kicked her out pregnant, but she returned five years later with something that changed everything.

The first lie Elena Vega ever heard in the Salcedo penthouse sounded like a compliment. “You’re so… lucky,” Carmen Salcedo…

“Papa… my back hurts so much I can’t sleep. Mommy said I’m not allowed to tell you.” — I Had Just Come Home From a Business Trip When My Daughter’s Whisper Exposed the Secret Her Mother Tried to Hide

Aaron Cole had practiced the homecoming in his head the way tired parents practice everything: quickly, with hope, and with…

End of content

No more pages to load