The summer heat in the American South had a way of pressing itself onto everything, like a palm that refused to lift. It sat on the hood of the rental car, on the cotton fields sliding by in pale green rows, on the backs of Marcus “The Comet” Hayes’s hands as he drummed his fingers against his knee and stared out the passenger window.

They’d been driving since Atlanta, headed toward a speaking engagement in a small town that barely made the map unless you were already lost and looking for someplace to admit it. The highway signs grew thinner, then older, then almost embarrassed by their own existence.

It was 1974, but some roads didn’t believe in calendars.

Angelo Rossi sat behind Marcus, half-asleep, with a rolled-up program tucked into his shirt pocket and a cigarette that had burned down to a stubborn little nub. Angelo had trained fighters for half his life, the kind of man who could watch a shadow shift and tell you what punch was coming next.

Next to him, in the other back seat, was Reggie “Bunny” Brown, Marcus’s assistant, hype man, and human siren. Bunny could turn a cough into a rallying cry and a sandwich into a prophecy.

Up front with Marcus sat Howard Finch, longtime friend and photographer, camera bag on his lap like a sleeping animal. Howard watched Marcus the way a seismologist watches a mountain: not expecting it to move, but knowing it could.

“We’ve been on this road two hours,” Howard said, voice dry. “If I see one more billboard for boiled peanuts, I’m going to write a memoir and it’ll be titled Help.”

Bunny leaned forward between the seats. “Champ don’t need memoirs. Champ needs food. Food makes fists happy.”

Angelo grunted. “Food makes everyone happy.”

Marcus didn’t answer. He was listening to the car itself, the soft whine of tires, the hum of heat, the way the air conditioner struggled like it had personal problems.

They rounded a bend and the trees opened up. A small building appeared on the roadside, squat and tired, with peeling paint and a parking lot made of dirt that had been pounded flat by years of pickups.

A diner.

And in the window, taped up like a bad joke that wouldn’t die, a handmade sign:

WHITES ONLY. NO COLORED SERVED.

Bunny saw it first. His voice changed, as if somebody had turned down his volume and tightened his throat at the same time.

“Champ,” he said. “Keep driving.”

Howard sat up straighter. He didn’t lift his camera yet, but his fingers found it.

Angelo leaned forward. “Marcus. Don’t.”

Marcus’s jaw flexed once, slowly. His eyes didn’t blink. He stared at the sign long enough for the words to become more than ink.

It wasn’t just the sign. It was the fact that it existed in daylight, without shame. It was the fact that it sat there like a law of nature.

The car rolled forward a few yards…and then Marcus eased it onto the shoulder.

Bunny exhaled a curse so soft it sounded like a prayer.

“Man,” Howard muttered, almost affectionate, almost doomed. “Here we go.”

Angelo’s hand reached out as if he could physically stop the moment by touching the back of Marcus’s seat. “We’ll find someplace else. We’re not here to—”

Marcus opened the door.

The heat hit them like a wall. The air smelled of dust, grass, and gasoline, with something fried lingering underneath.

He stepped onto the dirt and looked back at them.

His voice was calm, which was always the most dangerous part.

“I’m hungry,” Marcus said.

Bunny shook his head hard. “Champ, you’re hungry everywhere. You can be hungry at the next place.”

Marcus’s eyes flicked toward the diner again. “Not the point.”

Howard got out, camera already coming up. “If this ends up in the newspaper, I want the best angle.”

Angelo climbed out last, like a reluctant conscience in loafers. “Marcus, please. We got a schedule.”

Marcus started walking.

The bell above the diner door jingled when he pushed it open. It was a small sound, cheerful and ordinary, which made everything that happened after feel even sharper.

Inside, time felt thicker. The place was dim, ceiling fans turning lazily, stirring air that tasted like grease and old coffee. Vinyl booths lined the walls. A long counter stretched across the front, with stools bolted down like they had no intention of letting anyone leave quickly.

About fifteen customers sat scattered around: white men in work shirts, a woman with her hair in a tidy helmet, an elderly couple with hands linked on the table like a habit.

Every conversation died the instant Marcus stepped in.

The room stared at him, and then, a heartbeat later, recognized him.

Fame was its own kind of light. It had a way of showing up before you did.

Behind the counter stood a man in his fifties, thick through the shoulders, face deeply tanned and deeply set, wearing a greasy apron over a white undershirt. His name, stitched on the apron, read CAL.

Cal Whitaker. Owner. Inheritor. Gatekeeper.

For a split second, Cal’s expression flashed with something like excitement. A celebrity in his diner. A story he could dine on for years.

Then the excitement curdled into something harder.

“We don’t serve your kind,” Cal said loudly, making sure the whole room heard him. “Can’t you read the sign?”

The words landed heavy. They were meant to slam a door shut without even moving.

The elderly couple in the corner stood up quietly. The man helped his wife with her purse, and they left without looking at anyone, like they were escaping a fire that hadn’t started yet.

Marcus walked to the counter at an unhurried pace. Each step felt measured, not because he was afraid, but because he understood stagecraft. He knew how attention worked. How silence could be held.

When he spoke, his voice was calm, almost friendly. “I can read.”

Cal’s eyes narrowed. “Then read yourself out.”

Marcus didn’t smile yet. “I’ve read the Constitution,” he continued, still calm. “I’ve read the Civil Rights Act. And I’ve read my own life enough to know that hate’s taught, not born.”

Bunny shifted behind Marcus, hands clenched at his sides. Howard stood slightly to the left, camera hovering, unsure whether to take the shot now or wait for the moment that would become history.

Cal leaned forward. “This is my property. I got a right to refuse service to anyone I want. You don’t like it, you can go be famous somewhere else. Before I call the sheriff.”

Marcus’s gaze held steady. “You know who I am?”

Cal snorted. “Yeah. You’re that boxer. Cash—”

“Marcus Hayes,” Marcus corrected gently. “Heavyweight champion.”

A few people in the diner swallowed hard. The title had weight. Even the most stubborn prejudice could recognize power when it came wrapped in belts and headlines.

Cal crossed his arms. “So?”

Marcus nodded, as if Cal had answered a question properly. “So I could come behind that counter right now,” Marcus said, voice still even, “and there wouldn’t be much you could do about it.”

Cal’s hand moved down toward something under the counter. Bunny saw it and stiffened, ready to spring. Angelo’s shoulders tensed like he was back in a corner between rounds.

Marcus didn’t move.

“I could tear down that sign,” Marcus continued. “I could make a scene. I could do what folks expect me to do when they think of fighters.”

He paused, letting the idea hang there. The whole room held its breath with it.

“But I’m not going to,” Marcus said.

Cal blinked, thrown off balance. “Why not?”

Marcus’s face softened in a way that didn’t feel weak. It felt deliberate.

“Because I didn’t come in here to fight you,” he said. “I came in here to ask you something.”

Cal’s eyes flicked to the customers, looking for backup, looking for the old choir to sing the old hymn. But nobody met his gaze. Even the men who looked angry stared at their plates like the food might offer instructions.

“What question?” Cal snapped.

Marcus leaned his forearms on the counter, casual as if ordering pie. “Who taught you to hate?”

The words slid under Cal’s defenses. You could see it happen. His mouth opened, ready for another bark, but the question had moved the conversation off the battlefield and into a room Cal didn’t like visiting.

“My daddy,” Cal said after a moment, like he was spitting something out. “My daddy taught me. Whites and…others don’t mix. That’s how it’s always been.”

Marcus nodded slowly. “And who taught your daddy?”

Cal’s jaw worked. “His daddy, I guess.”

“And who taught him?” Marcus asked quietly. “And who taught him?”

Cal’s face reddened, but not with the old fury. With something closer to discomfort.

“Three generations,” Marcus said, voice calm, almost sad. “Passing hate down like it’s a family recipe.”

Angelo shifted, lowering his voice as he leaned toward Bunny. “This is the part where Marcus starts talking, and the world starts changing.”

Bunny didn’t take his eyes off Cal. “Or the part where somebody does something stupid.”

Howard finally lifted his camera and snapped a shot. Not of Marcus, but of Cal’s face. The moment before a man realizes his certainty has cracks.

Marcus turned his head slightly, scanning the diner. “How many of you agree with him?” he asked the customers. “How many of you think that sign is right?”

Silence answered first.

Then a woman in her forties, hair pinned tight, spoke without standing. “Cal,” she said, voice small but steady, “the law says you can’t have that sign.”

Cal’s eyes flashed. “I don’t care about the law.”

But his voice lacked its earlier steel. It sounded like a man trying to convince himself.

Marcus turned back to him. “I grew up in Louisville,” he said, taking a breath. “When I was a kid, my bike got stolen. I was so angry I wanted to fight the thief with my bare hands. A police officer told me, ‘You better learn how to fight first.’ He taught me how to box.”

Cal snorted. “And?”

Marcus’s gaze held. “He was white.”

That landed. Not because it was dramatic, but because it was simple.

“My trainer here,” Marcus said, gesturing slightly to Angelo, “he’s white. Some of my toughest opponents were white. Some of the folks who’ve saved me in my life were white.”

He leaned forward a fraction. “And you know what I learned?”

Cal didn’t answer, but his eyes stayed on Marcus now, as if he couldn’t help it.

“White people aren’t all the same,” Marcus said. “Black people aren’t all the same. Good and bad live in every color. That sign in your window tells me you don’t believe that.”

Cal’s voice came out rough. “That’s different. Those are your people. Your…work people.”

Marcus shook his head once. “No,” he said, firm. “They’re just people.”

The diner held the kind of silence that wasn’t empty. It was full of listening.

Marcus’s voice softened again. “When I look at you, Cal, I don’t see a white man. I see a man who’s scared.”

Cal’s face twisted. “I ain’t scared of nothing.”

“Yes, you are,” Marcus said gently, like he wasn’t accusing, just describing. “You’re scared of change. Scared your daddy would be disappointed. Scared your customers will leave. Scared that if you admit you were wrong, you’ll have to look at your life and realize you spent years guarding a door that didn’t need guarding.”

Cal’s hands trembled slightly. He clenched them into fists to hide it.

Bunny’s voice broke the quiet, unable to stay silent any longer. “Champ,” he said, half warning, half pleading. “We don’t gotta do this.”

Marcus didn’t look back. “Yes,” he said softly. “We do.”

Because the truth was, Marcus Hayes had just come from a victory that made him feel larger than life. Three months earlier, he’d fought in Africa under a sky full of heat and history and taken back the title the world had tried to deny him. He’d heard crowds roar his name like it was a prayer.

But out here, in rural America, there were still signs that said his name didn’t matter. That belts didn’t matter. That laws didn’t matter.

He wasn’t fighting for a cheeseburger.

He was fighting for the simple idea that the door should open the same for everyone.

Marcus reached into his pocket and pulled out a folded bill. He set it on the counter gently, like an offering.

“I want to buy lunch for everyone in here,” he said. “Doesn’t matter who. I want people to eat together, as equals.”

Cal stared at the money like it might bite him. “I ain’t taking your money.”

Marcus tilted his head. “Why not?”

Cal’s mouth opened, and then closed.

Marcus’s voice lowered just enough that only Cal could clearly hear him, though the room leaned in anyway.

“Cal,” he said, “you’re going to get older. One day you’ll sit on a porch somewhere and watch the years go by like cars passing on a highway. And you’ll ask yourself what you stood for.”

Cal’s eyes glistened, and he hated it.

“Are you going to be proud,” Marcus continued, “that you kept a racist sign in your window? Are you going to tell your grandkids you once refused service to a hungry man because of the color of his skin?”

Cal swallowed hard.

“Or are you going to tell them about the day you changed,” Marcus said, “the day you decided to be better?”

Cal’s voice cracked, a sound that surprised even him. “I don’t know how.”

Marcus’s face warmed, not triumphant, not smug. Just human.

“You start,” Marcus said, “by taking down that sign.”

Time stretched.

Cal looked at the customers. The men who used to laugh at his jokes didn’t smile now. The woman who’d mentioned the law watched him like she was waiting for him to remember he had a soul.

Cal looked at Marcus Hayes, the champion standing in his diner as if he belonged there, as if he had always belonged there.

Then Cal walked from behind the counter.

He moved slowly, like each step was a negotiation with his own past. He reached the window, grabbed the paper sign, and for a moment his hands hesitated.

In that hesitation lived generations.

Then he tore it down.

The sound of ripping paper was small, but it felt louder than the bell over the door. Cal crumpled the sign in his hands, crossed to the trash can, and dropped it in.

When he turned back, tears were running down his face.

“I’m sorry,” he said. The words came out broken. “I’m sorry for the sign. I’m sorry for turning people away. I’m sorry I been…a hateful man.”

A long breath released from somewhere in the diner, like the building itself had been holding it.

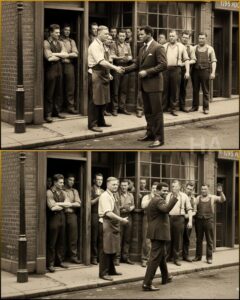

Marcus stepped forward and put a hand on Cal’s shoulder.

“That’s the bravest thing I’ve seen all week,” Marcus said quietly. “And I fought the toughest man in the world.”

For a heartbeat, nobody moved.

Then someone clapped. Then another. Then the diner erupted into applause that sounded like relief, like people had been waiting years for permission to become better than their fathers.

Howard Finch snapped photos as fast as his camera would allow, his own eyes stinging. Angelo exhaled, a laugh caught in his throat, half disbelief, half gratitude.

Bunny wiped his face with the back of his wrist and muttered, “Lord have mercy…Champ out here punchin’ hate without swingin’.”

Marcus looked at Cal and finally smiled, wide and hungry and alive.

“Now,” Marcus said, “how about that lunch? I’m starving.”

Cal laughed through tears, the sound awkward, unused. Then it steadied.

“Comin’ right up,” he said. “Champ.”

That afternoon, Marcus sat at the counter and ate a cheeseburger and fries like it was the simplest thing in the world. The diner door opened and closed again and again, people drawn by rumor and heat and the strange electricity of change.

At first, only white customers came in, peeking, curious, cautious.

Then a Black man in a work cap stood outside for a long moment, staring at the window like it might still be lying. Cal saw him, froze, then walked around the counter and held the door open.

“You hungry?” Cal asked.

The man blinked, uncertain. “I…uh.”

Cal cleared his throat, voice thick. “We got burgers. Coffee. Pie if it ain’t all gone.”

The man stepped in slowly, like entering a church after years away. People watched, and then looked away, ashamed of watching.

Marcus lifted a hand in greeting. “Come on,” he called. “Sit. Food tastes better when everybody’s allowed to chew.”

The man’s shoulders loosened. He slid onto a stool two seats away from Marcus, still wary, still expecting a trap.

Cal poured him coffee with hands that still shook.

Outside, the sun didn’t soften. But something inside the diner did.

When Marcus and his crew finally stood to leave, the air felt different, as if the building had been scrubbed from the inside out.

Cal followed Marcus to the door.

“I just want you to know,” Cal said, voice low, “you changed my life today.”

Marcus’s expression turned serious. “You changed your life,” he corrected. “I just…showed you the mirror.”

Cal nodded, wiping at his eyes. “You think I can really keep doing it? Keep…being better?”

Marcus held his gaze. “I’ll be checking on you.”

Cal gave a shaky laugh. “You famous folks always say stuff like that.”

Marcus smiled. “I’m not famous to you right now. I’m just a man who’s going to remember this door.”

Over the next few years, Marcus kept his word.

Whenever his travels took him through that stretch of the South, he’d tell the driver to swing by Whitaker’s Diner, the same building now with fresh paint and a new sign that simply read:

WELCOME.

The first time he returned, Cal had hired his first Black employee, a teenage boy named Isaiah who moved fast and smiled cautiously, as if he didn’t trust kindness yet.

The next time, Cal had rearranged the booths, tearing out the old “preferred seating” habit without needing to say it aloud. People sat where they sat. Conversation flowed where it flowed.

By 1978, half the staff was Black. The other half was white. The kitchen was loud with shared jokes and shouted orders and the kind of ordinary harmony that used to feel impossible.

Cal started going to community meetings. He spoke awkwardly at first, like a man learning a new language with an old tongue. But he kept showing up.

And the thing about change was, it grew when fed.

Other owners, hearing what had happened at Whitaker’s, quietly took down their own signs. Some did it in the middle of the night, ashamed. Others did it in public, trying to borrow Cal’s courage. A few refused and watched their businesses wither, clinging to a past that was crumbling anyway.

Marcus never bragged about that day. When reporters asked him about it, he’d shrug and say, “I had a conversation with a man.”

But the people who were there knew it wasn’t just conversation. It was a kind of fight, one fought in words and patience and the stubborn belief that people weren’t doomed to become their worst inheritance.

In 1980, Cal Whitaker wrote Marcus a letter. The handwriting was rough, as if his hand still wasn’t used to tenderness.

He thanked Marcus for “knockin’ sense into me without throwin’ a punch.”

He wrote about his children. About the first time his daughter brought home a friend who was Black and how, instead of feeling fear, he felt shame for ever having made the world smaller for her.

He wrote, You taught me strength ain’t hate. It’s the courage to change.

Years later, when Cal was sick and the diner had long since become a community landmark, his family called Marcus’s office. Cal wanted Marcus to know one last thing.

That cheeseburger he’d served in 1974, the one he’d cooked with shaking hands and a newly clean window, was still the proudest meal he’d ever made.

The building that once held Whitaker’s Diner stands still in rural America, though it’s no longer a diner now. It became a community center, the kind with folding chairs and bulletin boards and kids’ laughter echoing where silence used to sit.

On one wall hangs a small plaque. It doesn’t mention belts or titles. It doesn’t mention fame.

It reads:

On this site, a man chose to be better. And another man reminded him he could.

The fight against hate isn’t won in one punch, or one law, or one famous moment. It’s won in a thousand small decisions. A thousand doors held open. A thousand signs torn down.

Sometimes all it takes is one person brave enough to walk through the door, not to destroy, but to speak.

And sometimes, the bravest thing a man can do is admit he was wrong, then pick up a broom and start sweeping his own heart clean.

THE END

News

He Brought His New Wife to the Party—Then Froze When a Billionaire Kissed His Black Ex

The invitation arrived in a thick, cream envelope that looked like it had never known the inside of a mailbox….

Billionaire’s Son Pours Hot Coffee on Shy Waitress –Unaware The Mafia Boss Saw Everything

The first scream didn’t belong in a place like The Gilded Sparrow. The cafe sat in San Francisco’s financial district,…

In Court, My Wife Called Me “A Useless Husband” — Until The Judge Asked One Question…

The clock above the judge’s bench read 9:14 a.m. and sounded louder than it should have, as if every second…

“‘By Spring, You Will Give Birth to Our Son,’ the Mountain Man Declared to the Obese Girl”

Snow fell like quiet verdicts, one after another, flattening the world into a white that felt too clean for what…

Choose Any Woman You Want, Cowboy — the Sheriff Said… Then I’ll Marry the Obese Girl

The first light of morning slid through the thin cracks in the cabin wall like it was ashamed to be…

She Was Deemed Unmarriageable—So Her Father Gave Her to the Strongest Slave

They said I would never marry. They didn’t say it kindly, either. They said it the way people in polished…

End of content

No more pages to load