In the winter, the world still felt unfinished.

Out on the far edge of the Dakota Territory, where the sky didn’t simply hang above you but seemed to widen like a promise, the wind traveled unhindered for miles, combing the prairie grass flat and leaving no secret unruffled. The land breathed cold that season, a kind of cold that crept into seams and hinges and the soft places behind a person’s ribs. People out there learned to speak plainly, work hard, and keep their feelings tucked tight as coins in a pocket.

Back in Peoria, Illinois, a young woman named Mabel Rose Hart held a letter as if it might burn her.

It wasn’t a fancy letter. No gilded edges, no lavender scent, no lace folded inside. Just a page of careful handwriting, ink pressed firm enough to show through to the other side. But it carried something larger than paper: a doorway.

Mabel sat at her narrow kitchen table, the same table where her mother had once rolled dough for Sunday pies and later, when sickness thinned her to a shadow, had rested her forehead to pray the pain away. That table had become Mabel’s workbench after the funeral, crowded with spools of thread, needles, scraps of cloth, and the blunt little scissors that had bitten through thousands of hems.

A seamstress’s tools. A seamstress’s life. Honest. Small. Predictable.

The letter promised different.

Miss Hart,

I am seeking a wife of good character to share my homestead near Cedar Ridge. I have land enough for cattle, a house sturdy against winter, and intentions that are serious. I am not a man of flowery speech, but I can promise you this: you will not want for safety under my roof. If you are willing to come West, I will meet you at the platform in Cedar Ridge when the train arrives.

Silas Crowley.

Mabel had read those words so many times they felt like a second heartbeat.

Silas Crowley didn’t mention her looks. That fact had sat in her chest like a quiet relief. The men in Peoria who had tried to court her had always done it with a kind of half-joking assessment, eyes dropping to her hips as if her body were a ledger they were balancing.

Some called her “sturdy.” Others used sharper words when they thought she couldn’t hear. Even women, sometimes, with that practiced smile that could cut as clean as a blade.

Mabel had been born with a generous figure and a laugh that came easy. Her face held soft lines at the corners of her mouth from too much smiling through too many hard years. She wasn’t dainty. She wasn’t the sort of girl who could float through a room unnoticed. She took up space, and the world seemed to resent her for it.

But Mabel had a spirit bigger than most men could hold.

When she laughed, it was sunlight. When she worked, it was steady as a metronome. When she loved, it was fierce, the kind of love that didn’t ask permission to exist.

After her mother died, the house had become too quiet. The streets of Peoria had begun to feel too narrow. Every day looked like the one before: mend a seam, patch a tear, bow your head, and hope the future didn’t ask anything more of you.

Then came the letters.

One. Then another. Then a third, each arriving like a small tug westward. Silas wrote about the creek that cut through his land, about the way the snow piled against the barn door, about needing a woman’s hands in a place built for endurance.

And Mabel, who had spent her life stitching other people’s lives back together, wondered what it might feel like to stitch her own into something new.

So she sold what she could.

Her little sewing table, worn smooth at the corners. Her mother’s dishes, chipped but beloved. Even the lace curtains she had hemmed with her own hands, each stitch a quiet prayer her mother might live long enough to see another spring.

She kept only what mattered: her mother’s quilt, heavy with history; her sewing kit, the true extension of her hands; and a single trunk that held the rest of her life folded tight.

On the morning she left, the air smelled like coal smoke and snow.

A neighbor woman hugged her too hard and whispered, “You be careful, Mabel. Men out there are… different.”

Mabel had smiled gently.

“They’re men everywhere,” she said. “And I’ve survived them here.”

The train groaned like an old animal as it pulled away, steam hissing and wheels biting into frozen tracks. Mabel sat by the window, watching Illinois flatten into distance, watching towns become smudges, watching the familiar give way to the unknown.

As the days passed, the landscape changed. Trees thinned. The horizon widened. The cold sharpened.

At night, in her narrow sleeper seat, Mabel pressed her palm against her trunk as if it could anchor her. She wondered what Silas looked like. She wondered if his eyes were kind. She wondered if he had meant the word “safety” the way she needed it.

She also wondered, in the quietest part of herself, whether she was a fool.

But hope, when a woman is hungry for it, can taste like bread.

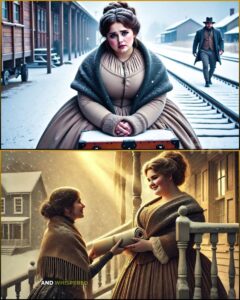

By the time the train reached Cedar Ridge, the world outside was white and restless.

Snow fell in thick, swirling sheets, making the platform look like something half-erased. The station itself was a weathered little building with a slanted roof and windows fogged from the inside. A single lantern swung near the door, throwing a weak gold halo into the wind.

The train doors opened with a reluctant clank.

Mabel stepped down into the storm with her shawl pulled tight and her breath rising in ghostly puffs. The cold struck her like a slap, but she steadied herself, gripping the handle of her trunk and looking out at the town that was supposed to become her future.

Cedar Ridge was not much. A cluster of wooden buildings, a few muddy streets buried under slush, a livery stable, a saloon with light glowing behind its windows, and faces that looked carved from wind.

Mabel’s heart beat faster as she scanned the platform.

She expected a man waiting with purpose. A glance of recognition. A hand lifted in greeting.

Instead, there was only snow.

She waited.

Ten minutes passed. Then twenty.

A man leading a horse walked by and tipped his hat politely, but he didn’t slow. A group of boys threw snowballs near the livery, laughing as if the cold were a joke. A woman in a heavy coat hurried into the station without looking at Mabel at all.

The wind picked up, pushing snow against Mabel’s skirt, icing the hem. Her fingers began to numb around the trunk handle.

Still she waited, telling herself Silas might be delayed. That the storm might have slowed him. That he had meant what he wrote.

Finally, through the curtain of snowfall, a figure appeared.

Broad-shouldered. Hat pulled low. Coat dusted white. He walked toward her with the slow certainty of someone approaching a chore, not a miracle.

When he reached her, he stopped close enough that Mabel could see the hard line of his mouth.

He did not smile.

He did not take her hand.

He nodded once, like a man acknowledging the arrival of a shipment.

“Miss Hart,” he said.

His voice was not cruel, but it wasn’t warm either. It had the flatness of a door being shut.

“Yes,” Mabel answered, forcing steadiness into her tone. “Mr. Crowley.”

Silas reached for her trunk and lifted it onto the back of a wagon without meeting her eyes.

Mabel waited for some softer word, some sign that he understood what she had done to stand there in the snow. She waited for him to say her name like it mattered.

Instead he clicked his tongue at the horse.

“Come on,” he said, already turning away. “It’s a long ride.”

She climbed into the wagon beside him, pulling her shawl tighter as the wheels creaked forward.

The ride out to his homestead felt longer than miles could explain.

The prairie rolled wide and silent, the snow covering everything in a ruthless sameness. Silas said little, and when he did speak, it was only about practical things: the condition of the road, the state of the barn roof, the need to mend a fence once the weather broke.

Mabel tried to fill the silence.

“It’s beautiful out here,” she offered, though her teeth were chattering.

“Cold,” Silas replied.

“Yes,” she said softly. “Cold.”

She watched his hands on the reins. They were strong hands, work-worn, the hands of a man who could build and break and survive.

But there was no gentleness in them as they held the leather. No softness in the way he moved.

When they reached the homestead, Mabel’s first sight was a house hunched against the wind, sturdy as promised but with windows that looked like they hadn’t seen laughter in years. A barn sat nearby, half-sheathed in ice. A line of cottonwoods rattled in the wind like dry bones.

Silas helped her down and carried her trunk inside without ceremony.

The house smelled of smoke and soap. It was clean but spare. A table, a few chairs, a stove, a bed tucked into a corner.

Mabel stood by her trunk, trying to make her heart match the steadiness of the room.

Silas removed his hat and set it on a peg. He still hadn’t looked at her properly. Not once. His gaze slid around her as if he were avoiding a truth.

The silence between them grew thick enough to choke on.

Finally, he spoke.

“Come out back,” he said.

Mabel followed him behind the barn, the snow crunching under her boots. The wind whipped her shawl. A lone cow lowed somewhere in the distance, a sound like loneliness itself.

Silas stopped near the barn wall and faced her at last.

His eyes were pale and assessing. Not cruel, but… measuring.

Mabel’s stomach tightened.

He cleared his throat.

“You’re not what I expected,” he said.

The words dropped like stones.

Mabel felt them hit her chest, heavy and immediate.

“Oh,” she managed, though the sound barely left her throat.

Silas rubbed a hand over his jaw, as if irritated with himself for having to say it.

“You seem like a fine woman,” he added, almost reluctantly. “I can tell. But I was thinking someone… smaller. More delicate.”

He said it plainly, like he might say, I was expecting a different kind of horse.

Mabel blinked hard. The wind stung her eyes, and for a second she could pretend that was the reason for the wetness gathering there.

She forced her chin up.

“I see,” she said.

Silas shifted his weight, looking past her shoulder at the snow-covered ground.

“I can’t,” he muttered. “I’m sorry. I need… I need what I need.”

Mabel waited for him to offer something else. A plan. An apology with shape. A kindness. Anything.

But Silas had already turned away, as if the matter were settled.

Mabel stood there for one heartbeat too long, her mind trying to catch up to the reality that had just been spoken.

She had sold her life for this.

She had ridden west with hope stitched into every corner of her heart, and now she was being told, behind a barn, that her body was the wrong shape for love.

She did not cry loudly. She did not beg.

She simply nodded once, carefully, like her heart might crack if she moved too fast.

“Thank you for meeting the train,” she said, her voice quiet but steady.

Silas didn’t answer.

Mabel turned and walked away.

Her boots crunched in the snow. Her shawl snapped behind her in the wind like a flag refusing to lower.

She didn’t know where else to go.

So she went back toward the station, not because she had a plan, but because her legs needed somewhere to carry her and the platform was the only place she had already survived.

The snow fell harder on the way back, biting at her cheeks. By the time she reached the tracks, the train was long gone, and the town looked even smaller under the weight of winter.

Mabel sat on a bench inside the station, her trunk beside her like an accusation.

She did not have a return ticket.

She did not have a room.

She did not know a soul.

Tears slipped down her cheeks, not loud, not wild, just steady. Quiet grief, the slow unraveling of everything she had dared to believe.

A station clerk glanced at her once and looked away. A man in a fur hat pretended not to notice. The world kept moving, as it always did, even when one person’s life split open.

Only when her fingers had gone numb and her legs stiff with cold did she rise, not because she had found direction, but because sitting in the cold wasn’t living.

She picked up her trunk.

She turned her back to the empty tracks.

And she walked into Cedar Ridge.

The town received her the way winter received everything: without tenderness.

People looked at her trunk first, then at her face, then at her body. Their eyes held that familiar flicker Mabel had learned to recognize, the silent arithmetic of judgment.

At the far edge of town she found an apothecary with a room for rent upstairs.

The apothecary was run by a woman named Mrs. Larkin, whose hair was iron-gray and whose eyes had the sharpness of someone who’d watched too many people pretend kindness while doing harm.

“You got money?” Mrs. Larkin asked bluntly when Mabel inquired about the room.

“Some,” Mabel admitted.

“Two weeks paid in advance,” Mrs. Larkin said. “After that, you better have a plan.”

“I do,” Mabel lied, because she needed the room more than she needed honesty in that moment.

The room was small and drafty, with a slanted roof and a single bed that creaked when she sat. A tiny stove squatted in the corner like a tired animal. The window let in more cold than light.

But it was dry.

And for now, it was hers.

That first night, Mabel unpacked her mother’s quilt and spread it across the bed. The familiar weight of it felt like a hand on her shoulder.

She sat on the edge of the mattress and let the quiet settle.

In the distance, she could hear laughter from the saloon and the faint jangle of a piano. It made her feel both outside and invisible, like a ghost hovering near the warmth she couldn’t enter.

Mabel pressed her fist against her mouth and breathed through the ache in her chest.

She did not allow herself to think of Silas Crowley’s eyes.

She did not allow herself to think of how quickly hope could become humiliation.

Instead, she opened her sewing kit.

Needles. Thread. Thimble.

Tools she understood.

If the world insisted on breaking her, she would stitch herself back together.

In the days that followed, Mabel began to build a life in Cedar Ridge the only way she knew how: thread by thread.

She offered mending services to townsfolk. Split seams. Worn hems. Patches for boys who tore their pants sliding on frozen hills. Fixes for men who worked too hard to worry about buttons until the wind punished them for it.

She baked pies when she could, trading slices at the small café for eggs and flour. She washed her own clothes in icy water and hung them by the stove, the steam making the tiny room smell like clean persistence.

She asked for no favors and told no tales.

But still, the whispers found her.

“That’s the mail-order bride who got turned away.”

“Poor thing. Shame about her figure.”

“Did you hear she waited in the snow like a fool?”

Mabel walked through town with her shoulders back, her chin up, her lips pressed tight like stitches.

She had heard worse.

And besides, being rejected didn’t mean being ruined.

Mrs. Larkin, in her blunt way, offered small mercies without calling them kindness. She let Mabel take leftover coal ash to keep her stove going. She didn’t ask questions when Mabel came home late, hands red from cold, eyes too bright.

At the bakery, Mrs. Pritchard slipped Mabel day-old bread in exchange for a quick repair on her apron.

“Good to have another woman in town who understands keeping things together,” Mrs. Pritchard whispered one morning, her voice carrying something like solidarity.

Mabel smiled and nodded, swallowing the lump that formed in her throat.

It wasn’t much, but it was something.

And then there was the general store.

The general store in Cedar Ridge was the heart of the town, selling everything from nails to ribbons, from molasses to lamp oil. The bell above the door chimed all day, announcing the comings and goings of life.

Mabel preferred to go mid-morning, when the store quieted and the crowd-thick air of gossip thinned.

The first time she went in, she needed thread and flour. The second time, buttons. The third time, she told herself it was molasses, but she wasn’t entirely sure she believed that.

That’s when she noticed him.

His name was Thomas Whitaker, though most people called him Theo like it was easier to say with cold lips.

He worked behind the counter, tall and soft-spoken, with spectacles perched on his nose and a way of moving that suggested crowds exhausted him. He wasn’t flashy. He didn’t laugh too loud. He didn’t lean into gossip.

He was simply… steady.

As Mabel set her coins on the counter one morning, Theo glanced at the book peeking from her basket. A slim volume with a worn spine, something she’d carried from Illinois like a secret.

“You like to read?” he asked.

His voice was quiet but kind. Not the kind of kind that felt performative, but the kind that existed even when no one was watching.

Mabel blinked, surprised.

“Yes,” she said. “Romances, mostly.”

Theo’s mouth twitched, the beginning of a smile.

“Happy endings?” he guessed.

Mabel let out a small breath that almost became laughter.

“Lately,” she admitted, “I’ve needed them.”

Theo nodded as if he understood that need intimately.

“I might have one or two tucked in the back,” he said. “If you’d like to borrow.”

Mabel hesitated. Borrowing a book felt strangely intimate, like being handed a piece of someone’s private world.

But Theo’s eyes held no judgment, only the calm patience of a man who didn’t rush anything worth having.

“I’d like that,” she said softly.

The next time she came in, a slim novel wrapped in brown paper sat by the register.

“No charge,” Theo murmured when she reached for her coins. “Just bring it back when you’re done.”

Mabel stared at the package, then at him.

“That’s… very kind.”

Theo shrugged, almost embarrassed.

“Books ought to be shared,” he said. “They do better that way.”

Mabel took the book home and read it by the weak light of her candle, the words warming her more than the stove ever could. When she returned it, carefully wrapped again, Theo asked what she thought of the heroine, and Mabel found herself talking about the story as if it were a real place she’d visited.

They spoke longer the next time. About characters, then about the weather. About pie crusts. About prairie grass and how time seemed to move differently in winter, slower and sharper.

Week by week, their conversations grew.

Not too long. Not too forward.

But something began to stretch between them, warm and gradual, like sunlight melting ice without anyone noticing until the ground was soft again.

Theo never mentioned Silas Crowley.

He never brought up the gossip that clung to Mabel like dust.

He looked at her as if she wasn’t a town story, but a person. As if she were a book he was still reading, curious and willing to wait for the next page.

And that, more than anything, began to heal the bruise inside her.

One morning in late winter, Mabel walked into the store with a basket on her arm and the stubborn feeling that the air had shifted. The snow outside was still deep, but the light had changed, brighter at the edges, like spring was pacing nearby waiting for its turn.

Theo looked up as the bell chimed, and something in his expression softened further than usual.

“You’re early,” he said.

“I had a tear to fix for Mrs. Pritchard,” Mabel replied, setting a small parcel on the counter. “And I thought I’d pick up flour.”

Theo glanced at the parcel.

“What’s that?”

Mabel cleared her throat.

“A tart,” she said, suddenly shy. “Cranberry. I made it yesterday.”

Theo blinked, caught off guard.

“This is too kind,” he said.

Mabel smiled.

“Kindness isn’t meant to be measured, Mr. Whitaker.”

Theo’s gaze lifted to her face, and for a moment the store around them seemed to fade. There was no evaluating in his eyes. No arithmetic. Only seeing.

He looked at her like he was understanding something he’d been reading between the lines for weeks.

Mabel felt the warmth of it all the way to her fingertips.

Their talks deepened after that, though still careful.

Theo asked, one quiet afternoon, “Do you miss home?”

Mabel’s throat tightened.

“Sometimes,” she admitted. “Mostly, I miss my mother. The rest… I think I miss the idea of it more than the truth.”

Theo nodded slowly.

“My wife used to say the same thing about her childhood,” he said, voice soft.

Mabel startled.

“You were married?” she asked gently, realizing she’d assumed too much from his quietness.

Theo’s fingers stilled on the ledger he was writing in.

“Yes,” he said. “Her name was Margaret. She died three winters ago. Fever.”

“I’m sorry,” Mabel whispered.

Theo’s smile was small and sad, but not broken.

“Me too,” he said. “For a long time, I thought that was the end of everything good that could happen to me.”

Mabel didn’t know what to say, so she simply stood there, letting the honesty settle between them like something sacred.

As she turned to leave, Theo called her name.

“Mabel.”

She paused, looking back.

“This place feels different when you’re here,” he said.

The words were simple, but they struck deep.

Mabel’s eyes stung. She forced a smile.

“That’s a dangerous thing to say to a woman who reads romances,” she teased, trying to lighten the weight of her own feelings.

Theo’s mouth curved, his eyes warm.

“Maybe I’m a dangerous man,” he said, so quietly it felt like a secret.

Mabel walked home through the snow with that sentence tucked under her shawl like a hidden flame.

Spring began to tease Cedar Ridge slowly, as if the land didn’t quite trust it yet.

Snow melted into rivulets along the roads. The air carried the faint scent of wet earth. Windows opened just enough to let in fresh air and the sounds of life waking up.

In her small upstairs room above the apothecary, Mabel worked on something at night.

Her mother’s quilt had traveled a thousand miles with her, worn and familiar, stitched with the lives of women who came before her. But Mabel began adding new squares to it, pieces cut from this new life she was building.

A bit of faded gingham from Mrs. Pritchard’s bakery apron. A patch from her own shawl. A strip of fabric that matched the ribbon Theo had once admired when he’d wrapped a book for her.

Every square was a memory. Every stitch, an act of choosing to stay.

When the quilt was finished, Mabel folded it carefully, wrapped it in brown paper, and tied it with twine. Her hands trembled just a little, not from cold but from the vulnerability of giving something made from her history.

She carried it to the general store on a morning when the sky was pale blue and the air smelled like thaw.

The bell chimed as she stepped inside.

Theo looked up.

“Mabel,” he said, and the way he said her name made her feel like she belonged somewhere.

“I have something for you,” she said, placing the bundle on the counter.

Theo untied the twine gently and unfolded the quilt layer by layer. His fingers moved slowly over the stitching, pausing on the worn edges and the new patterns.

“You made this,” he said, voice quieter than usual.

Mabel nodded.

“It was my mother’s,” she said. “But I added to it. I thought… maybe it could keep your chair warm. You sit so long back here.”

Theo stared at the quilt, then at her.

His eyes looked suddenly bright, like he was fighting something.

“No one’s ever given me something like this,” he said.

Mabel swallowed.

“Well,” she whispered, “no one’s ever made me feel safe enough to.”

Theo stepped around the counter.

He didn’t rush. He didn’t grab. He simply took her hand, his rough fingers closing gently around hers as if he understood that hands could be both tools and tenderness.

“Mabel Rose Hart,” he said, and the sound of her full name in his mouth made her chest ache. “You are the most beautiful woman I have ever seen.”

The air left her lungs.

Not because she didn’t believe him, but because for the first time, she finally did.

She blinked rapidly, trying not to cry in the middle of the general store.

Theo’s thumb brushed her knuckles, a small, steady gesture.

“I don’t mean it like a compliment meant to be taken and then forgotten,” he added quietly. “I mean it like truth.”

Mabel’s voice came out thin.

“Most men would laugh at a truth like that.”

Theo’s gaze didn’t waver.

“Then most men are fools.”

Mabel laughed, a surprised sound that cracked open something inside her. It wasn’t loud. It wasn’t pretty. It was real.

And Theo smiled like that was exactly the sound he’d been waiting to hear.

But life, especially on the frontier, rarely allowed joy to arrive without testing whether you could hold it.

A week later, Mabel was delivering a repaired coat to a man near the livery when she saw a familiar wagon turning down the main road.

Her stomach tightened before her mind even caught up.

Silas Crowley sat stiffly on the bench, reins in hand, his pale eyes scanning the town.

He was in Cedar Ridge.

Mabel’s fingers went cold.

She told herself he had business. That he might not even notice her.

But Silas’s gaze landed on her like a weight.

He pulled the wagon to a stop.

“Mabel,” he said, as if he had the right to say her name now.

Mabel lifted her chin.

“Mr. Crowley,” she replied evenly.

Silas looked her up and down in a way that made old shame try to rise. Not because she believed his opinion mattered, but because memories had teeth.

“I heard you stayed,” he said.

“I did,” Mabel answered.

Silas’s jaw tightened.

“You shouldn’t have,” he said, then seemed to realize how that sounded and added, “I mean… Cedar Ridge isn’t kind. Folks talk.”

Mabel’s mouth curved, humorless.

“Yes,” she said. “I’ve noticed.”

Silas hesitated. For the first time since she’d met him, he looked… uncertain.

“I didn’t mean to humiliate you,” he said, and the words sounded like something he’d practiced, not something he’d felt.

Mabel studied him. He looked the same as he had behind the barn, hard-edged and purposeful. But there was something else now too, something like discomfort. Not regret, exactly. More like the irritation of consequences.

“Yet you did,” Mabel said quietly.

Silas exhaled, impatient.

“I was honest,” he insisted. “A man has the right to be honest about what he wants.”

Mabel’s eyes sharpened.

“And I have the right to exist without being evaluated like livestock,” she replied.

Silas flinched as if slapped.

A few people nearby slowed, pretending not to listen while very clearly listening.

Silas lowered his voice.

“I came because… because I made a mistake,” he said.

Mabel’s heartbeat stumbled.

She did not want hope to rise, not here, not with him.

“What kind of mistake?” she asked cautiously.

Silas’s gaze flicked away.

“I thought I needed a delicate woman,” he said stiffly. “Someone who would fit the picture in my head. But the winter’s been hard. The house is… empty. I find myself thinking—”

He cut himself off, like the words tasted bitter.

Mabel waited.

Silas forced himself on.

“Maybe I judged too quickly,” he said.

The town seemed to hold its breath.

Mabel felt something strange in her chest, not joy, not triumph, but a quiet clarity.

She looked at Silas Crowley, this man who had rejected her body like it was a flaw, and she realized something important.

Even if he did take her now, it would not be love. It would be convenience, loneliness, and the slow poison of being tolerated.

Mabel shook her head slowly.

“You didn’t judge too quickly,” she said. “You judged correctly, for the kind of man you are.”

Silas’s brows drew together.

“What does that mean?” he demanded.

“It means,” Mabel said, her voice steady, “that you wanted a woman to fill a space in your house, not a woman to know. You wanted a shape, not a soul.”

Silas’s face reddened.

“That’s not fair.”

“No,” Mabel replied softly. “What happened to me behind your barn wasn’t fair. This is simply the truth.”

Silas stared at her, anger and embarrassment wrestling in his expression. He looked, for a brief moment, like a man who had never been told no.

Then his gaze shifted past her shoulder.

Mabel turned, following it.

Theo Whitaker stood in front of the general store, a box of supplies in his arms, having clearly witnessed enough to understand what was happening.

His face was calm, but his eyes were sharp with something protective.

Silas saw him, and something in Silas’s expression twisted.

“So that’s it,” Silas muttered. “You’ve found someone else.”

Mabel felt her cheeks warm, not with shame but with the fierce desire to protect what she and Theo had built.

“I didn’t find him,” she said. “I found myself. And he saw it.”

Theo began walking toward them, setting the box down on the porch as he approached. His pace was unhurried, but there was a quiet authority in it that made people step back.

Silas squared his shoulders.

“This is between me and her,” he snapped.

Theo’s voice was even when he spoke.

“It stopped being between you and her the moment you made her stand alone in the snow,” Theo said.

Silas’s eyes narrowed.

“And who are you supposed to be?”

Theo glanced at Mabel before answering, as if asking silently whether she wanted him to step in.

Mabel met his gaze and nodded once.

Theo turned back to Silas.

“I’m the man who’s been reading her like she’s worth more than a first impression,” he said. “And I’m the man who won’t let you take another piece of her dignity.”

Silas’s nostrils flared.

“She came here for me,” he said. “She answered my letters.”

Mabel stepped forward, her voice ringing clearer than she expected.

“I came here for a new life,” she said. “And I’m the one who gets to decide what that life looks like.”

Silas’s jaw clenched so hard it seemed it might crack.

“People will talk,” he warned, leaning closer. “They’ll say you’re ungrateful. They’ll say you’re… loose.”

Theo’s eyes flashed, but Mabel lifted a hand gently, stopping him.

She faced Silas fully.

“Let them talk,” she said. “I’ve learned something out here, Mr. Crowley. The wind will always have something to say. But I don’t have to shape myself to its noise.”

Silas stared at her, then at Theo, then at the small circle of townsfolk who were now openly watching.

Finally, as if realizing he had already lost, Silas yanked his reins.

“This town is full of fools,” he muttered.

Then he turned his wagon and drove away, wheels cutting through slush like a retreating storm.

The moment he was gone, the air released.

People began to disperse, murmuring. The gossip would bloom, of course. But something else bloomed too: a new story, one where Mabel stood upright and chose herself.

Theo picked up the box again and looked at Mabel.

“You all right?” he asked softly.

Mabel exhaled, realizing her hands were shaking.

“I think,” she said, voice trembling with the aftermath, “I’m more than all right.”

Theo’s eyes warmed.

“You were brave,” he said.

Mabel laughed, the sound half shaky, half triumphant.

“I was terrified.”

Theo’s smile deepened.

“Those can live in the same house,” he said. “Bravery and fear.”

Mabel reached out and touched his sleeve.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

Theo hesitated, then covered her hand with his own.

“I didn’t do it for thanks,” he said. “I did it because I can’t stand the idea of anyone making you feel small.”

Mabel’s throat tightened.

She looked at this quiet man, this steady man, and felt something settle in her chest like a promise kept.

Spring moved forward after that, bold and insistent.

The town held its annual Spring Harvest Dance in the schoolhouse, stringing lanterns from the rafters and sweeping the floor until it looked almost respectable. A fiddler tuned up near the front, and the scent of lemonade and fresh bread filled the room.

Mabel almost didn’t go.

Old habits of hiding tried to pull her back. The memory of whispers. The fear of being watched.

But Mrs. Pritchard had appeared at her door that afternoon with a basket and a stern look.

“You’re going,” Mrs. Pritchard declared.

“I’m not sure—” Mabel began.

Mrs. Pritchard cut her off.

“Hush,” she said. “You made yourself a dress, didn’t you?”

Mabel flushed.

It was true. She had. Soft lilac with cream buttons, fitted at the waist in a way that made her feel like her own body was something to celebrate rather than apologize for.

Mrs. Pritchard nodded, satisfied.

“Then you’re going,” she said again. “And if anyone looks at you sideways, they’ll answer to me.”

Mabel couldn’t help smiling.

So she went.

She arrived alone, her hair pinned neatly, her lips touched with rose balm, her lilac dress catching lantern light like a quiet defiance.

She told herself she only wanted to watch. To feel part of something for an evening.

But the moment she stepped inside, Theo Whitaker’s eyes found her.

He stood near the punch table in a freshly ironed shirt, his usual quiet demeanor softened by nervousness he was clearly trying to hide.

Then he walked toward her.

Not quickly. Not timidly.

Like a man who had decided.

“Mabel,” he said, voice low.

Mabel’s breath caught.

Theo offered his hand.

“Would you dance with me?” he asked.

The room felt suddenly very still.

Mabel glanced around at the people who had whispered, who had watched her walk through snow and sorrow with her head high.

“Are you sure?” she asked gently, though her eyes were already shining.

Theo smiled, and the certainty in it made her chest ache.

“Very sure.”

Mabel placed her hand in his.

His grip was warm, steady, like an anchor.

They stepped onto the floor as the fiddler began a slow waltz. The music rose, bright and lilting, and the world narrowed to the feel of Theo’s hand on her waist, the weight of her palm on his shoulder.

They were not perfect dancers. They stumbled once, laughed softly, adjusted.

But it was real.

And as they moved together, Mabel realized something: the whispers didn’t matter. Not when she was being held like she was precious.

Theo leaned slightly closer.

“You look… like spring,” he murmured.

Mabel laughed under her breath.

“Is that your way of saying I’m thawing?” she teased.

Theo’s eyes crinkled.

“It’s my way of saying,” he replied, “that you make me believe in new beginnings.”

Later, under the stars outside the schoolhouse, the air cool and sweet with the scent of wet earth, Theo turned to her.

“I never expected to find love here,” he said. “Not after Margaret. Not after I convinced myself my heart was finished.”

Mabel’s throat tightened.

“And then?” she whispered.

Theo looked at her like she was the only light in the prairie night.

“Then you walked into my store,” he said. “And it was like everything I thought I’d lost came back. Not the same, but… new. And better, because it’s you.”

Mabel’s eyes filled.

“You didn’t just look at me,” she said, voice trembling. “You saw me.”

Theo stepped closer.

“I’ve been seeing you,” he said. “Every day since the first.”

When he kissed her, it wasn’t rushed or unsure. It was the kind of kiss that said: I’m here. I’m not going anywhere. You don’t have to shrink to be loved.

Mabel felt years of quiet shame loosen, like stitches being cut free.

She pressed her forehead against his afterward and breathed.

“I used to think being ‘too much’ was my curse,” she whispered.

Theo’s hand cupped her cheek, gentle.

“Too much for the wrong man,” he said. “Exactly enough for the right one.”

A year later, beneath a sky bright with summer promise, Mabel stood under a blooming wild plum tree behind the general store.

Her dress was cream lace she had sewn by hand, each stitch a reminder that her hands had always been capable of building beauty. The breeze played with the hem of her gown. Wildflowers dotted the hill, and the prairie stretched wide and soft beyond it, endless as possibility.

Theo stood beside her, his hands a little shaky, his eyes steady on hers like she was the one thing he’d been searching for without knowing it.

The town gathered, lanterns hung from branches, laughter woven through the air like music. Mrs. Larkin stood near the front, arms crossed, pretending she wasn’t pleased. Mrs. Pritchard dabbed at her eyes with her apron and pretended she wasn’t crying.

When Mabel looked out at all of them, she felt something warm and fierce swell in her chest.

She had arrived here in snow, carrying a trunk and a broken hope.

She had been rejected, judged, measured.

And yet she had stayed. She had stitched herself into this place until it could no longer pretend she didn’t belong.

Theo took her hands.

His voice was quiet but clear when he spoke his vows.

“I never knew peace until I met you,” he said. “Not the kind of peace that comes from silence, but the kind that comes from being seen and still being wanted. You are my home, Mabel Rose. If you’ll have me, I will spend my life proving that you were never too much. You were simply waiting for someone who could hold all of you.”

Mabel’s eyes blurred with tears.

She squeezed his hands.

“I crossed a thousand miles because I believed in a promise,” she said, her voice strong despite the tremble. “That promise broke. But I didn’t. I found something better than what I came for. I found love that doesn’t ask me to shrink. I found a man who reads me like I’m worth every page. Theo Whitaker… I will choose you, every day, as fiercely as I chose to stay alive when winter tried to convince me I was alone.”

Theo’s breath hitched, and the look in his eyes made Mabel feel like the whole wide sky had bent closer to listen.

When they kissed, the town cheered like they’d witnessed something rare.

And maybe they had.

Later, as the sun dipped low and the light turned gold, Mabel and Theo danced in the grass behind the store where it had all begun. The quilt Mabel had made was draped over a chair nearby, fluttering slightly in the breeze like a flag of survival.

Theo rested his forehead against hers.

“You changed my life,” he whispered.

Mabel smiled, her eyes bright.

“No,” she said softly. “You just reminded me who I already was.”

And if you ever find yourself standing in a cold place, feeling like the world has decided you are too much or not enough, remember this:

A woman can be turned away in the snow and still walk into spring.

A heart can break and still keep beating.

And love, real love, doesn’t ask you to be smaller.

It simply holds you.

THE END

News

THE DUKE PAID $10 FOR A “SILENT” BRIDE — HE GASPED WHEN SHE SPOKE 7 LANGUAGES

Rain didn’t fall in polite little drops that Tuesday. It came down like it had a grudge, drumming on the…

STRUGGLING WIDOWER MEETS “TOO FAT” BRIDE ABANDONED AT RAILROAD STATION, MARRIES HER ON THE SPOT

The wind had teeth that evening, snapping at the porch rails and tugging at the thin curtains like it wanted…

SHE WAS REJECTED FOR HER CURVES — BUT THAT NIGHT, A LONELY RANCHER COULDN’T RESIST

Dry Hollow, Colorado Territory, Winter, looked like the kind of place the world forgot on purpose. The wind came in…

MAIL-ORDER BRIDE WAS REJECTED FOR BEING “ALREADY PREGNANT” UNTIL ONE MAN BECAME HER CHILD’S FATHER

The train arrived like an animal that had run too far on too little mercy. Steel screamed. Brakes shrieked. The…

A POOR GIRL LET A MAN AND HIS DAUGHTER STAY FOR ONE NIGHT, NOT KNOWING HE WAS A MILLIONAIRE COWBOY

The first thing Emma Caldwell heard was breath. Not her own. Not the hiss of wind pushing powdery snow off…

SHE SAID “I’M TOO OLD FOR LOVE,” UNTIL THE COWBOY SAID “I’VE WAITED MY WHOLE LIFE FOR YOU”

The wind didn’t just blow in late winter along the Yellowstone. It worked. It worried the cottonwoods until they creaked…

End of content

No more pages to load