Clara Bennett didn’t cry in Dr. Caldwell’s office, not because she wasn’t humiliated, but because she’d learned that tears were a kind of currency in Silverpine, Colorado, and people like her always paid double. The doctor’s waiting room smelled of carbolic and polished wood, and the women sitting on the benches held their purses like they were guarding saints’ relics. Clara stood near the door, hands clenched in the folds of her dress, the fabric damp where her palms had sweated through it. When Dr. Caldwell finally looked at her, he didn’t look long, as if her skin might stain his reputation by proximity alone. His gaze skated over the angry red patches on her forearm and neck, paused just enough to register disgust, then flicked toward the door like a man directing livestock out of a parlor. “I don’t treat your kind,” he said, voice smooth as varnish, and the words landed with a crack that made the whole room feel smaller.

Clara’s throat tightened, but she forced sound through it anyway. “It burns at night,” she whispered. “It spreads. I can’t sleep, and I can’t work, and—” She didn’t get to finish. Dr. Caldwell lifted a hand, not unkindly, but with the practiced impatience of someone who had never needed to beg for help. “Miss Bennett, I have other patients,” he replied, and the women on the bench shifted, as if to place extra distance between themselves and whatever Clara was becoming. He leaned in just enough to lower his voice, which somehow made it worse, like sharing a secret no one should hear. “I cannot have you sitting in my waiting room, frightening decent people. You understand.” And then he turned away, already reaching for his next file, already erasing her from the story he wanted the town to believe about itself.

Outside, the autumn air tasted of coal smoke and cold iron. Clara stood on the boardwalk beside the clinic, staring at her own hands as if they belonged to someone else, someone she could abandon. The skin on her knuckles was raw from scratching in her sleep, and the red patches looked like shame made visible, a scarlet letter that didn’t even have the courtesy to be a single word. She could picture the evening ahead with sickening clarity: her mother’s careful silence, her father’s tight jaw, the way neighbors’ eyes would slide away and then back again, hungry for detail. She could hear the boys near the livery stable already, calling her “contagious” or “cursed,” as if cruelty were a public service. The thought of walking home, of carrying this rejection into the small house that was already heavy with worry, made her chest seize. So Clara did what desperate people do when the polite doors close: she chose the one path everyone warned her against.

The rumors had always sounded like campfire stories, stitched together from fear and curiosity. Jonah Rourke, the mountain man who lived above the tree line in a cabin most folks had never seen. Jonah Rourke, who set bones and delivered babies and cured fevers with plants and patience, who took payment in eggs or flour or nothing at all. Jonah Rourke, who’d come to Silverpine once years ago and left again before the town could decide whether to call him savior or menace. Clara had heard mothers whisper that he was dangerous, that he had “strange ways,” that a respectable girl had no business near him without a chaperone and a prayer. Clara had also heard a quieter rumor, the kind people didn’t say loudly because it threatened the town’s sense of order: Jonah Rourke didn’t care what you looked like. He cared whether you were hurting. In the space between one heartbeat and the next, Clara realized she’d rather risk the unknown than rot inside the known. By dawn the next morning, she had a carpetbag, a handful of coins, her sewing kit, and her grandmother’s last letter tucked into an inside pocket like a charm against despair.

The climb into the Rockies felt like walking up the spine of the world, each step dragging more pain out of her body than she thought it could hold. Aspen leaves, already turning gold, trembled in the wind like a thousand tiny warnings, and the air thinned until every breath felt borrowed. Clara’s dress clung to her where sweat met inflamed skin, and the friction turned movement into punishment. She stopped once, leaning against a pine tree, pressing her forehead to bark rough enough to remind her she was still real. Below, Silverpine looked deceptively peaceful, smoke curling from chimneys, morning light brushing rooftops, as if the town weren’t built from gossip and quiet cruelty. Clara pictured her mother at the kitchen table, staring at the place where Clara should have been, and she almost turned back on instinct alone. Then her forearm flared with a hot, sharp sting, and the memory of Dr. Caldwell’s voice rose up like bile. She lifted her chin and kept going, because anger, she discovered, could be fuel when hope ran low.

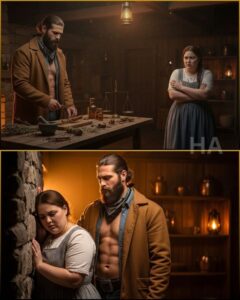

When the cabin finally appeared, it didn’t look like the lair of a beast, no matter what the stories had promised. It sat in a clearing like something earned: sturdy logs, a stone chimney with smoke rising in a steady thread, windows with actual glass that caught the morning sun. There was a small barn, a chicken coop, and a garden plot half asleep for winter, all signs of permanence rather than hiding. Clara’s heart hammered as she crossed the clearing, because the last of her courage had been spent on the climb and now she had to spend more on asking. The door opened before she reached the porch steps, and the man who stepped out wasn’t wild-eyed or ragged. Jonah Rourke was tall, broad-shouldered, his dark hair tied back neatly, his face clean-shaven as if he’d chosen order on purpose. He watched her approach the way a hawk watches weather: still, assessing, not wasting motion.

“Mr. Rourke?”

Clara’s voice came out smaller than she wanted. She hated that even now her body tried to make her sound apologetic for existing.

“I am,” he replied, and his voice was deep, quiet, edged with an accent that didn’t belong to Silverpine. His eyes flicked over her, not lingering on her size or the sweat streaking her temples, but pausing on the way she favored her left side, the way her breath caught shallow in her chest.

“I… I need help,” Clara said, and the words nearly cracked in half under the weight of how many times she’d said them before.

Jonah’s gaze sharpened, clinical in a way that made her flinch, until she realized it wasn’t judgment. It was focus. “You’re ill,” he said, as if naming a fact could take some of its power away. “Come inside.”

The cabin smelled of herbs and woodsmoke, clean and organized like a mind that refused chaos. Shelves lined the walls, crowded with jars and bundles of dried plants tied in twine, and a large table sat at the center, scrubbed so thoroughly it looked pale in the firelight. Jonah moved with efficient calm, filling a basin with warm water, selecting leaves and roots with the care of a man handling truths. Clara sat where he pointed, hands twisting in her lap, feeling the old fear crawl up her spine. In Silverpine, men only asked to see a woman’s body when they meant to take something, and Clara’s life had taught her to expect taking. Jonah set the steaming basin on the table beside her, and when he met her eyes his expression didn’t soften into kindness so much as settle into seriousness. “Let me see you,” he said.

Clara’s skin went cold under the heat of her embarrassment. Her hands flew to her collar. “What?” she managed, voice paper-thin.

“I need to see the affected areas,” Jonah replied, tone flat with practicality. “I can’t treat what I can’t examine.”

The words should have been reasonable. They were reasonable. But shame is not a reasonable creature, and it rose up snarling anyway, armed with every insult she’d ever swallowed. Clara stood abruptly, chair scraping the floor. “I should go.”

“You climbed three hours to get here,” Jonah said, and his voice shifted, not louder, but sharper, as if he was cutting through fog. “Your breathing is labored. You’re flushed. You’re in pain beyond what you’re admitting. If you leave now, you’ll go down worse than you came up, and Dr. Caldwell will still refuse you. That’s not pride, Miss Bennett. That’s self-destruction.”

Clara froze with her hand on the doorframe, because the brutal part was that he was right. Jonah’s voice softened, not into sweetness, but into steadiness. “I’m not him,” he said. “I’m not interested in punishing you for being sick. This is medicine, not cruelty. If you want my help, you need to let me do my work.”

Something in his certainty steadied her, like a hand on her back that didn’t push, only supported. Clara turned, breathing hard, and began to unbutton her dress with fingers that shook. She expected disgust. She expected the flinch. Instead Jonah stepped back slightly, giving her space, eyes focused on the task the way a craftsman focuses on a cracked beam he intends to mend. When the last layer fell away and the angry patches of inflammation showed clearly, Jonah didn’t recoil. He circled her slowly, examining without touching until he asked, “May I?”

Clara nodded, jaw tight.

His fingers were warm and careful as he turned her arm toward the light, pressing gently on an unaffected area and watching how the skin responded. “Not contagious,” he murmured, almost to himself. “Inflammation, fluid retention. Your body is fighting something it can’t name.” He looked up at her then, and his gaze held a kind of blunt respect. “This isn’t your fault.”

The sentence hit Clara harder than any insult ever had, because it was the first time someone had offered her mercy without conditions. Tears burned behind her eyes, but she blinked them back fiercely, unwilling to fall apart in front of a stranger. “Can you help me?” she asked anyway, because pride was a luxury she’d already spent.

“Yes,” Jonah said, and there was no drama in it, only truth. “It won’t be quick, and it won’t be easy, but yes.”

Relief flooded her so fast her knees weakened. Jonah began mixing a compress from herbs and a thick base that smelled sharp and clean. “Twice a day,” he instructed, “more if the burning returns. And you need rest. Real rest. Not the kind where you lie down and still feel hunted.” He glanced at her, and Clara heard the question forming before he spoke it. “Where were you planning to go after this?”

The silence that followed was answer enough. Clara had come seeking treatment, but she hadn’t planned beyond survival.

“You can stay here,” Jonah said, and the words landed like a door opening to a room she’d never known existed. “There’s a back room. Clean. Private. No charge.”

Clara stared. “Why?” The question scraped out of her throat raw, because kindness always came with hooks in Silverpine.

Jonah’s hands paused. He didn’t look away. “Because once,” he said quietly, “I was the one a doctor decided wasn’t worth the trouble. And someone took me in anyway. He asked only that I pass it forward.” He set the compress in her lap, gaze steady. “So. Will you stay, Miss Bennett? Will you let me help you?”

Clara thought of the town below, of whispered judgments and doors closing. She thought of this cabin that smelled like work and warmth rather than shame. She swallowed, and the word she spoke felt like stepping onto new ground. “Yes,” she whispered. “Please.”

The days that followed didn’t feel like a miracle so much as a method, and that was its own kind of wonder. Jonah treated her skin with patience, adjusting herbs based on how her body responded, explaining what he saw and why it mattered. He changed her diet, not with scolding, but with reasoning: certain foods worsened inflammation in some people, and they needed to find what set her body on fire. When Clara flinched at the restrictions, expecting judgment, Jonah’s eyes narrowed. “This isn’t about your weight,” he said, voice firm enough to stop her spiraling. “This is about your immune system. Don’t let anyone convince you you deserve pain as punishment.” Under the routine, her body began to remember relief. Under Jonah’s calm, her mind began to loosen its grip on fear.

As her strength returned, Clara couldn’t bear idleness, and she offered what she had always had: her hands and the skill in them. Jonah opened a trunk full of fabric he’d been paid in and let her choose what she needed. She measured windows, stitched curtains, mended shirts, and with every neat seam she felt something inside her stitch back together too. Even the silences between her and Jonah changed, becoming less tense and more companionable, like shared air rather than avoided words. One evening, as firelight flickered across the table, Clara admitted, “My mother only ever looked proud when I sewed. Everything else about me… disappointed her.” Jonah set down his book and said, without softness but with certainty, “Then her shame was never yours to carry.” It wasn’t a magical absolution, but it planted a seed of anger in Clara that felt cleaner than shame.

Winter pressed in early, and with it came Marisol Ortega, a young ranch wife with a belly heavy with her first child and fear written in the tightness around her mouth. Jonah examined her carefully, then said words that turned the cabin into a place braced for battle. “Breech,” he confirmed. “We’ll try to turn the baby, but if she won’t move, you stay here. No pride, no foolishness. I’m not losing you because people think propriety matters more than breathing.” Marisol’s husband, Diego, hovered like a man trying to hold back a storm with his hands. Clara stepped beside Marisol and said quietly, “You won’t be alone here. I’ll be here too.” The tension in Marisol’s shoulders eased just a fraction, as if the presence of another woman made the world less sharp.

Then came the morning the past tried to drag Clara back by the ankle. Voices outside, male voices, too many, and the scrape of hooves on snow. Jonah stood in the doorway like the cabin itself had grown a spine, and Clara saw Dr. Caldwell on horseback, his coat fine, his expression full of righteous offense. “We have witnesses,” Caldwell said. “You’ve been keeping Miss Bennett here for weeks. This is improper. Dangerous.” Clara stepped forward before fear could decide for her, and the men stared as if she’d risen from a grave. They expected the hunched, inflamed woman they’d mocked. They found someone straighter, clearer-skinned, eyes bright with a dangerous thing called self-respect.

“My mother is worried sick,” Caldwell lied smoothly.

“My mother is embarrassed,” Clara corrected, voice steady. “There’s a difference.”

They spoke of reputation, of morality, of what a community had the right to demand, and Clara felt anger rise like heat in her chest, not destructive, but clarifying. “What reputation did I have before I came here?” she asked, letting the question hang where everyone could see it. “The fat seamstress’s daughter? The contagious girl? The shame of a respectable family? You didn’t care about my reputation when Dr. Caldwell refused to treat me.” She looked directly at Caldwell. “You said you don’t treat my kind. I remember your exact words.” The men shifted uncomfortably, as if the truth had a smell they didn’t like.

The confrontation might have ended in brute force if Diego hadn’t arrived, jaw set, declaring that his wife’s life mattered more than Silverpine’s gossip. And it might still have ended badly if Clara’s mother, Evelyn Bennett, hadn’t appeared at the edge of the clearing on a small mare, face pale, eyes determined. “Then I’ll be your chaperone,” Evelyn said, and the words sounded like a bridge being built over years of silence. Clara stared at her mother, stunned by the audacity of love finally choosing the harder path. When Evelyn met Clara’s eyes, something broke open there. “I failed you,” her mother said quietly. “I won’t do it again.” Caldwell sputtered about order and standards, but even some of the men on horseback began to look unsure, as if they’d ridden up the mountain expecting a scandal and found instead a mirror held too close.

The storm that sealed them in came three days later, a blizzard that wrapped the cabin in white silence and forced everyone to live with the choices they’d made. Inside, the work sharpened into preparation: boiled water, clean cloths, Jonah’s instruments laid out with careful precision. Marisol’s baby finally turned on a night when wind clawed at the walls, and the relief in Marisol’s sobs felt like prayer becoming real. Two days after that, labor began before dawn, contractions tightening like fists. Clara found herself holding Marisol’s hand, becoming an anchor when fear threatened to pull the young woman under. “I can’t,” Marisol sobbed at one point, exhausted, trembling. Clara leaned close and said, fierce and gentle all at once, “You can. You’re doing it right now. One breath at a time. We’re here.”

When the baby’s cry finally split the room, sharp and furious with life, Clara felt her own lungs fill as if she’d been the one gasping for air. Jonah lifted the newborn, slick and red and perfect, and his voice went rough around the edges. “A girl,” he announced. “Healthy. Angry. Exactly as she should be.” Marisol laughed and cried in the same breath, and Evelyn covered her mouth with shaking fingers, tears spilling down her cheeks as if she were watching a second chance being born alongside the child. Later, when Diego arrived as soon as the storm eased enough to let him climb, his knees hit the floor beside Marisol’s bed and he wept like a man learning gratitude has weight. Clara stood in the doorway, heart tight, understanding with sudden clarity why Jonah had chosen this life above the town. Healing wasn’t a transaction here. It was a covenant.

Spring came slow, and with it came people. A little girl with the same burning skin Clara had once carried. An old man with joints swollen and stiff. A young mother dismissed as “hysterical” until her headaches nearly stole her sight. Clara listened to them the way Jonah had listened to her, hearing the stories behind the symptoms, recognizing how often shame and stress were stitched into sickness. Word traveled down the mountain faster than any official could stop it, and Dr. Caldwell’s pride curdled into action. He filed a complaint with the territorial board, hoping paper and authority could do what compassion had undone: silence them.

When the board’s representative arrived, stern and sharp-eyed, Clara expected the end. She watched him inspect Jonah’s records, interview patients, examine outcomes, and every time his pen scratched a note, her stomach tightened. But on the last day, after he examined the little girl whose skin was already less inflamed, he set his papers down and said, almost grudgingly, “I came expecting a charlatan. I found competence.” His gaze shifted to Clara. “And I found an apprentice with remarkable bedside manner.” He spoke of pathways and examinations, of formal licensing that could protect their work rather than destroy it. Clara’s hands shook as possibility opened like a window after a long winter. When Jonah asked later if she wanted the burden of proving herself to a system that had never welcomed her, Clara answered without hesitation. “I want to,” she said. “Not for them. For me.”

She studied through summer, treated patients in between lessons, and took the examination in the territorial capital with her heart in her throat. When the panel asked why she wanted to become a healer, Clara didn’t offer a rehearsed line. She told the truth. “Because everyone deserves dignity,” she said, voice steady. “Because sickness isn’t sin. And because healing isn’t just curing skin or setting bones. It’s seeing someone’s worth when the world keeps trying to write them out.” Two weeks later, the letter arrived with an official stamp, and Clara read it three times before she could believe her own name beside the words recognized medical apprentice. Evelyn wept openly, not from shame this time, but from pride that had finally learned how to show itself.

Nearly a year after Clara’s first desperate climb, she stood on the porch watching autumn gild the aspens again, marveling at how the mountain had remade her. Jonah joined her, hands in his pockets, posture easy in a way it hadn’t been when she first arrived. “Do you remember the day you came here,” he asked, “when I told you to let me see you?” Clara nodded, cheeks warming at the memory of fear that now felt distant, like an old scar. Jonah’s voice softened into something she rarely heard, not sentiment, but sincerity. “When I looked at you, I didn’t see a burden,” he said. “I saw someone brave enough to keep moving. And watching you become what you were always meant to be… it reminded me why I do this.” He hesitated, then took her hand as if the gesture mattered enough to do carefully. “I asked you to stay because I needed help,” he admitted. “I’m asking you now because I can’t imagine this place without you. If you want… not just to work beside me, but to build a life beside me… I would be honored.”

Clara looked at their joined hands and thought of all the hands she’d held in the last year: Marisol’s in labor, Evelyn’s in apology, a frightened child’s when she swore the illness wasn’t her fault. She thought of Dr. Caldwell’s refusal, the moment that had shattered her and sent her climbing into the unknown. She thought of Jonah’s first words, the ones she’d heard as humiliation and learned were medicine. Then she lifted her gaze and let the answer be simple, because the truth didn’t need decoration. “Yes,” she said. “Yes to all of it.”

That winter, as snow softened the world outside, the cabin glowed with the warmth of chosen family. Evelyn hummed while stirring stew, her voice steady and unashamed. Marisol and Diego visited with their daughter bundled in quilts, the baby’s laughter bright as a bell. Patients still climbed the mountain, and Clara met them with clean hands, clear eyes, and a calm she’d earned the hard way. On Christmas Eve, Clara sat by the fire with Jonah beside her, watching the flames dance, feeling the quiet pulse of a life that fit her like a well-made garment. She didn’t miss Silverpine’s narrow kindness or its brittle standards. She didn’t miss shrinking herself to make others comfortable. She had found something better than acceptance. She had found purpose, dignity, and love that asked nothing of her except that she be alive in her own skin.

Outside, snow fell in patient silence, covering old tracks, smoothing rough edges, turning the world into a blank page. Inside, Clara Bennett held her mug of tea between warm palms and understood the truth that had taken her a lifetime to learn: she had never been broken, only treated as if she were. And on a mountain where compassion mattered more than reputation, she had finally been seen.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load