People liked to say the law was a blindfold. In Cedar Hollow, Georgia, it felt more like a gag.

The Cedar Hollow County Courthouse sat downtown like an old brick sermon, all white columns and chipped steps, the kind of building that looked noble from far away and tired up close. Inside, the air had its own history: floor wax layered over stale coffee, old paper, and the anxious salt of people waiting to be reduced to a number. The courthouse’s AC had been “temporarily broken” since the late 90s, according to a sign that looked like it had survived the Clinton administration on sheer stubbornness alone. The fans pushed warm air in lazy circles. The humidity pressed against skin like a hand that didn’t ask permission.

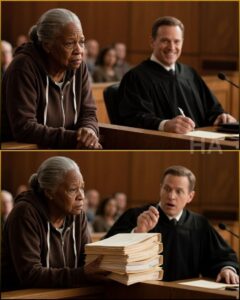

In Courtroom 4B, Judge Calvin Prescott held court the way a man holds a remote, thumb ready to mute whatever annoyed him. He was fifty-ish, ruddy-faced, blond hair slicked back with enough gel to qualify as a fire hazard. He didn’t sit upright in the high-backed chair so much as lounge in it, as if everyone else had wandered into his living room while he was mid-game.

He banged the gavel often, not for order, but for the small thrill of making grown people flinch.

At the back row, a woman sat very still, hands folded neatly as if they’d practiced patience for decades.

She was sixty-two, Black, and carried herself with the quiet economy of someone who’d learned that raising your voice was rarely the sharpest tool. Her name, on paper, was Naomi Caldwell. Today she wore gray sweatpants, comfortable sneakers, and an oversized navy hoodie with MYRTLE BEACH cracked across the front in white letters like fading chalk. Her hair, threaded with silver, was pulled into a plain bun. She looked ordinary. She looked tired. She looked, to the untrained and uncurious eye, like someone who’d been worn down by time.

But Naomi’s eyes were not tired. They were awake in the way of a lighthouse, sweeping, cataloging.

She watched the bailiff, Deputy Mitch Larkin, scrolling on his phone while a nervous young man tried to ask where to stand. She watched the clerk, Susan Kroll, roll her eyes as she shuffled files as though lives were junk mail. Most of all, Naomi watched Prescott, the man behind the bench, because he was the kind of man who believed the bench was a throne and the robe was armor.

Naomi had heard the stories for years. Her family roots ran through Cedar Hollow like an old riverbed. Her niece Vanessa lived three streets from the courthouse. Two weeks earlier, Vanessa had called Naomi sobbing so hard the words came out broken.

“Auntie… he didn’t listen. He didn’t even pretend to. He looked at Jamal, saw the tattoos, and gave him the maximum for a first-time noise complaint. He called him a thug, on the record. Like… like my boy is just a label.”

Jamal. Vanessa’s son. Naomi’s nephew by blood and by love.

Naomi knew the statistics. She knew the language of justice better than almost anyone alive. She had sat in courtrooms where the stakes were international, where the defendants had teams of attorneys and the press sat like vultures with notebooks. She had spent a lifetime studying the thin line between law and power, and how often power wore the law like a mask.

But hearing her own family treated like disposable noise in the town where Naomi had learned to ride a bike hit a different part of her chest.

It wasn’t professional anymore.

It was personal.

So Naomi took a leave of absence. She told her clerks in Washington that she was going fishing, said it lightly, with a smile that fooled the people who didn’t know her well. She didn’t tell them she was going fishing for a shark.

In her canvas tote bag, the document she carried wasn’t a case file the way people imagined. It was a property deed, plus a thin folder of meticulously prepared paperwork. The dispute was simple on its surface: a minor zoning issue tied to an old lot that had once belonged to her late mother. A shed, the city said, was unsafe. A violation. A nuisance. The kind of petty matter that could be used as a hammer if the judge wanted an excuse to swing.

Naomi had filed the paperwork with deliberate errors. Not enough to break the case. Just enough to tempt a lazy judge into showing his habits. She dressed down on purpose, wore the hoodie on purpose, moved slowly on purpose. She had constructed the perfect bait for a man who fed on the powerless.

Court began like a factory line.

A young woman stepped forward, trembling, there for an unpaid parking ticket. She tried to explain that she had been in the hospital on the date the ticket was issued.

“I don’t care about your medical history, Miss… Davis, is it?” Prescott cut her off, voice oozing boredom. “I care about the city’s revenue. Double the fine. Payment plan denied. Next.”

The girl’s mouth opened like she’d been slapped. Tears came fast, humiliatingly fast, and Deputy Larkin steered her away by the elbow, more shepherd than human.

Naomi felt something tighten behind her ribs. The old cold fire. The one that had pushed her through law school when professors suggested she might be “more suited” to support roles. The one that had guided her hands through years of opinions, dissents, arguments, decisions.

Prescott didn’t see himself as cruel. Men like him rarely did. He saw himself as efficient. He saw fear as order.

“Case number 4492,” Susan Kroll droned, eyes dead. “City of Cedar Hollow versus Naomi Caldwell. Zoning violation and failure to maintain property structure.”

Naomi rose.

Her knees popped slightly, because age was real even for legends, and she walked to the defendant’s table with deliberate calm. She didn’t stare at the floor. She looked straight at Prescott.

He was looking at his watch.

“State your name,” he muttered without lifting his eyes.

“Naomi Caldwell,” she said.

Her voice was low, clear. The kind of voice that didn’t need volume to command space.

Prescott finally looked up. He squinted, eyes dragging over her hoodie, her sweatpants, the absence of a lawyer at her side. A smirk grew like mold.

“Ms. Caldwell,” he said, leaning into his microphone so the speakers made him sound bigger than his soul. “You are aware this is a court of law, not a Walmart checkout line. We have a dress code.”

Deputy Larkin snickered. A couple of attorneys in the front row chuckled, the polite laugh of people who needed Prescott’s favor.

Naomi didn’t flinch.

“I apologize, Your Honor,” she said smoothly. “My luggage was lost in transit. I thought it more important to be here on time than to be fashionable.”

“Lost in transit,” Prescott repeated, savoring it. “Fancy way of saying you missed the bus.”

A ripple of laughter. Thin. Mean.

He flipped through the file like it was a menu he couldn’t be bothered to read.

“Let’s make this quick,” he said. “You have a shed on Fourth Street that’s an eyesore. The city wants it down. You haven’t responded to three letters. Why?”

“I never received the letters, Your Honor,” Naomi replied, calm as stone. “The address on file is for the property itself, which is uninhabited. Proper procedure dictates notice must be sent to the owner’s primary residence.”

Prescott paused. The legal logic landed clean. It was correct. It was basic. It was the kind of thing any judge should know before lunch.

For a moment, his face revealed the truth: he hadn’t read the file. He hadn’t cared to.

Then his ego took the wheel.

He didn’t like being corrected by a Black woman in a hoodie.

“Don’t quote the law to me, Ms. Caldwell,” he sneered. “I am the law in this room. You ignored the city. You’re wasting my time.”

Naomi’s expression didn’t change, but her spine felt straighter, like a blade being drawn.

“I am stating my rights to due process under—”

The gavel hit the wood so hard it sounded like a gunshot.

“Silence!” Prescott roared, face turning darker red. “You want to play lawyer? Go to law school. Until then, shut your mouth. I’m fining you five hundred for the structure and another five hundred for wasting the court’s time with your attitude.”

Naomi stood very still.

This was the hinge. The moment where the story either stayed small or opened its mouth wide enough to swallow him.

“With all due respect,” Naomi said, and her voice dropped into something deeper, something sharpened. “You cannot impose a punitive fine for a civil zoning infraction without an evidentiary hearing. That is a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

The courtroom went silent as if someone had pulled the plug on air itself.

The attorneys stopped chuckling. Deputy Larkin’s grin stalled. Even Susan Kroll looked up for the first time with something like curiosity.

That wasn’t how people in sweatpants spoke. Not in Prescott’s world.

Prescott blinked, stunned for half a second. Then his arrogance doubled down, because arrogance is a coward that masquerades as confidence.

He laughed. Loud. Barking. Ugly.

“The Fourteenth Amendment,” he said, wiping at the corner of his eye as if Naomi had delivered a comedy special. “That is rich. Listen to her. Been watching too much TV.”

His voice turned syrupy in the way disrespect often does when it wants to sound harmless.

“Let me tell you something, sweetheart. In Cedar Hollow, the Constitution is what I say it is.”

Naomi didn’t move.

Prescott leaned forward, savoring the power of having an audience.

“Now get out of my face before I hold you in contempt and throw you in a cell for the weekend.”

Naomi’s eyes were steady. “Is that a threat, Judge Prescott?”

“It’s a promise,” he spat. “Bailiff, remove this woman. And Deputy Larkin, check her for warrants. Usually when they talk this much, they’re hiding something.”

Deputy Larkin lumbered forward with the casual cruelty of someone who’d been told his hands were tools and nothing else. He grabbed Naomi’s arm too tightly, skin on bone, a grip designed to remind her who controlled doors.

Naomi pulled back with surprising strength and looked at him like winter.

“Do not touch me.”

The words weren’t loud, but they made his fingers twitch as if they’d been burned.

Naomi turned back to Prescott.

“You have made a grave error today,” she said, and then, because sometimes a scalpel is sharper than politeness, she added, “Calvin.”

She dropped “Your Honor” like a spent shell.

Prescott shot to his feet, veins rising in his neck. “That’s it. Thirty days. Contempt of court. Lock her up. Get her out of my sight.”

As Larkin grabbed her again and hauled her toward the side door, Naomi didn’t scream. She didn’t beg. She didn’t fight in the way Prescott wanted her to fight, because he loved desperation. He fed on it.

Instead, she maintained eye contact with him, expression unreadable, calm like a verdict already written.

Prescott thought he’d crushed another bug.

He didn’t know he’d swallowed poison.

The holding cell in the courthouse basement smelled like mildew and old fear. A single metal bench was bolted to the wall, and the toilet in the corner looked like a health hazard that had learned to be patient. Naomi sat with her back straight, hands resting on her knees. They had taken her phone and her tote bag, but they hadn’t taken her mind.

Two other women were in the cell.

One was a girl, nineteen at most, mascara streaked down her cheeks like somebody had erased her dignity with wet fingers. The other was a hard-eyed woman in her forties with a bruise blooming on her jaw like a bitter flower.

The bruised woman looked Naomi up and down. “What you in for, mama?”

Naomi smoothed her sweatpants. “Contempt of court.”

The woman whistled softly. “You mouthed off to Prescott? Girl, you got a death wish. That man put my brother away five years for a joint in his pocket. He a tyrant.”

Naomi nodded once. “A tyrant always has a weakness.”

The woman snorted. “Yeah? What’s his?”

“He believes he’s untouchable,” Naomi said. “Arrogance is a slow venom. You don’t feel it until you’re already dead.”

The younger girl sniffled, voice small. “I’m scared. I just… I didn’t have the money for bail. I’m gonna lose my job at the diner.”

Naomi turned toward her, and something softened in her eyes, as if the steel knew when to become shelter.

“What’s your name, child?”

“Becky,” the girl whispered.

“Becky,” Naomi said, gentle but firm, “you are not going to lose your job. When I get out of here, I’m going to make a phone call.”

The bruised woman laughed, harsh and tired. “When you get out? Mama, he gave you thirty days. By the time you get out, Prescott won’t even remember you exist.”

Naomi smiled then, small and chilling, the kind of smile you see on a storm cloud.

“He will remember,” Naomi said. “I’m going to make sure he remembers my name for the rest of his miserable life.”

Upstairs, Prescott was in his chambers eating a meatball sub like he’d earned it, marinara smearing his tie. A local defense attorney, Graham Hensley, sat across from him laughing politely, the way people laugh when a powerful man is sharing his cruelty like it’s a joke at a barbecue.

“Did you see her?” Prescott chuckled, mouth full. “Quoting the Fourteenth Amendment. Who does she think she is?”

Hensley’s laugh came thin. “She did speak well, Calvin. Her diction, it was… educated.”

“Educated?” Prescott scoffed. “Please. Probably a retired librarian who got bitter. She’s nobody.”

He wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “It’s about respect, Graham. You let one of them talk back, they all start doing it. I maintain order.”

He leaned back, pleased with himself, as if he’d written a philosophy book instead of abusing a bench.

Just then, the door opened. Susan Kroll stepped in, and for once her face wasn’t bored.

It was pale.

“Judge,” she stammered.

“What is it, Susan?” Prescott snapped. “I’m eating.”

“There’s… there’s a phone call for you. Line one.”

“Take a message.” He waved a hand like swatting a fly.

Susan’s hands were shaking. “It’s the governor’s office. And someone from the Department of Justice is on the other line.”

Prescott froze mid-chew.

“The governor?” he frowned, suspicion cracking through his confidence. “What for?”

Susan swallowed hard, voice dropping. “They’re asking about… a prisoner. Specifically the woman you just held in contempt. Ms. Caldwell.”

A small prick of unease crawled into Prescott’s gut.

“Why would the governor care about a zoning violator?” he muttered, trying to sound amused but failing.

“I don’t know, sir,” Susan whispered. “But… the man from the DOJ didn’t call her Ms. Caldwell.”

Prescott set the sandwich down slowly.

“What did he call her?”

Susan’s lips trembled. “He called her… Justice Caldwell.”

The word landed in the room like a dropped weight.

Justice.

Prescott stared, processing in slow motion, as if his brain was trying to deny the shape of the truth.

He lunged for his computer, fingers clumsy. Typed: Naomi Caldwell.

A formal portrait filled the screen. A woman in black robes stood beside the President of the United States. Regal. Stern. Powerful.

And unmistakable.

The same face as the woman in the Myrtle Beach hoodie.

Associate Justice Naomi Caldwell. United States Supreme Court.

Prescott’s face went gray under the red, like fear had drained the color out of him.

Graham Hensley stood up so fast his chair scraped. “I… I think I should go.”

“Sit down,” Prescott hissed, then swallowed hard. His tie still had sauce on it. His hands looked suddenly foreign, useless.

“This is a mistake,” he whispered, but deep down he knew it wasn’t. He remembered her eyes. The way she stood like she belonged to the room even when he tried to shrink her.

“Get Deputy Larkin,” Prescott croaked to Susan. “Tell him to bring her up. Now. Immediately. Bring her to my chambers. Not the courtroom. My chambers.”

Susan bolted.

Downstairs, the cell door clanged open.

Deputy Larkin appeared, and he didn’t swagger now. He looked like he’d seen a ghost and realized it knew his name. He held Naomi’s tote bag with both hands, as if it might explode.

“Ms. Caldwell,” he began, voice cracking. “The judge… he would like to see you. In his chambers.”

Naomi looked up slowly. She didn’t stand right away. She let him feel the weight of waiting.

“Yes, Deputy Larkin,” she said calmly.

He shifted, sweating. “Do you want your bag, ma’am?”

Naomi stood, smoothing her hoodie, and looked past him at Becky. “Don’t worry,” she told the girl. “I haven’t forgotten.”

Then she faced Larkin again, eyes cool.

“Keep it,” Naomi said. “I want my hands free.”

The elevator ride to the third floor felt like a funeral procession. Larkin walked half a step behind her, silent, breathing shallow. Naomi’s presence filled the metal box, not loud, not dramatic, just undeniable, like gravity.

When the doors opened, Larkin practically scrambled to hold them.

“This way, Justice,” he stammered, the title awkward in his mouth because he’d never intended to say it.

They reached the heavy oak door of the judge’s chambers.

Larkin knocked once, timid now, and pushed it open.

Prescott stood in the center of the room like a man waiting for a hurricane to decide if it wanted his house. He had removed his stained tie. He’d combed his hair. He held a bottle of sparkling water and a glass, hands shaking so badly the glass tapped against the bottle in nervous rhythm.

“Leave us,” Prescott ordered, voice too high.

Larkin vanished, closing the door softly as if sound itself might offend Naomi.

Naomi stood near the entrance and took in the room: the mahogany desk, the framed degrees, the golf trophies, the soft leather chair where Prescott sat like a king.

She looked finally at the man himself, now trembling inside his expensive walls.

“Justice Caldwell,” Prescott began, forcing a smile that looked like pain. “I… I cannot apologize enough. There has been a terrible misunderstanding.”

Naomi tilted her head slightly. “If you had known who I was,” she said, finishing his sentence for him, “you would have treated me with respect.”

“Yes,” he blurted, relieved she’d given him a script. “Yes, of course. Professional courtesy.”

Naomi stepped forward, each footfall quiet but heavy with consequence.

“But because you thought I was just Naomi from Fourth Street,” she said, “you treated me like cattle.”

Prescott swallowed. “Now, Justice, let’s not be dramatic. I run a tight ship. We get a lot of… riffraff. Sometimes patience wears thin. It’s a stressful job. You know that better than anyone.”

Naomi didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t have to.

“Do not presume to know what I know,” she said, and the temperature in the room seemed to drop. “I have presided over cases where men tried to blow up buildings. I have watched organized crime witnesses shake so hard they could barely hold a Bible. I have seen corporate fraudsters steal pensions from thousands and still smile for the cameras. And I have never, not once, denied a citizen their right to be heard.”

Prescott’s eyes flicked to the door, then back to her.

Naomi moved closer to his desk. She didn’t sit. She gripped the back of a guest chair, knuckles dark against leather.

“Do you know why I’m here, Calvin?”

He tried. “The shed…?”

“There is no shed,” Naomi said simply. “My mother’s structure was demolished five years ago. The lot is empty. If you had read the file, if you had glanced at the photos, you would have known that. But you didn’t look.”

Her gaze sharpened.

“You saw a Black woman in a hoodie and stopped thinking.”

Prescott’s mouth opened and shut. “I can dismiss the case right now. Expunge it. It’ll be like it never happened.”

“Oh, it happened,” Naomi replied. “And it has been happening a long time.”

She leaned in slightly, and the air between them tightened.

“I didn’t come here for zoning.”

Prescott blinked. “Then… why?”

“I came here for Jamal,” Naomi said.

Recognition struck him like a physical hit. He staggered back, bumping the desk.

“Jamal Turner,” Naomi continued. “My nephew. Vanessa’s son.”

Prescott stammered, scrambling for footing. “I… I didn’t know he was related to you.”

Naomi’s hand slapped the chair back, not hard, but decisive, like a period at the end of a sentence.

“That is the problem,” she said. “It shouldn’t matter.”

Her voice grew steadier, fuller, each word placed with the precision of a lifetime.

“Justice is not a country club. It is not a loyalty program. It is not ‘who you know’ and ‘who you golf with.’ It is the law.”

She reached into her hoodie pocket.

Prescott flinched instinctively, fear making him ridiculous.

Naomi pulled out a small digital recorder. A red light blinked.

“I have been recording since I walked through security,” she said. “I have you mocking my appearance. Refusing to review evidence. Issuing punitive fines without proper hearing. And I have you saying the Constitution is what you say it is.”

Prescott stared at the recorder like it was a snake on his carpet.

“You can’t use that,” he whispered. “Two-party consent state.”

Naomi’s smile was brief and sharp. “This is a public courthouse. You were performing official duties, speaking into a microphone in open court. The public already heard you. The record is the people’s.”

She lowered the recorder slightly.

“But even if you were right,” she added, “imagine how it will sound on the six o’clock news. Imagine what the state judicial conduct commission will think when they hear the voice of a judge bragging that the Constitution doesn’t apply.”

Prescott rounded the desk, desperation making him dangerous. “Give me that recorder. Let’s… let’s work this out. I have friends. Powerful friends.”

Naomi didn’t step back. “Sit down,” she commanded.

Prescott pointed a shaking finger. “You think you can come into my town and entrap me? I’m the victim here. You lied. You created a fake dispute. You committed perjury.”

“I conducted a sting,” Naomi corrected, calm and implacable. “And as for your friends…”

She glanced at the clock on the wall, as if she were tracking something more than time.

“It is 1:15 p.m. Right now, Special Agent Thomas Reynolds is walking into City Hall with subpoenas for the mayor’s financial records. And I believe the state police are executing a search warrant on your home computer.”

Prescott collapsed into his chair, legs giving out like bad scaffolding.

“My… my home?”

“You didn’t think I came alone,” Naomi said, and her voice softened, not in mercy, but in the way a doctor softens when delivering fatal news. “I have been building this dossier for six months. Kickbacks. The private probation pipeline. The sentencing patterns. The way certain defense attorneys always got ‘better outcomes’ for wealthy clients while poor defendants were crushed.”

His eyes filled with tears. “Please,” he rasped. “I have a family. My daughter is in college. This will ruin them.”

Naomi looked down at him, and for a moment her gaze held something like grief, not for him, but for the damage he’d sprayed across the town like poison.

“You should have thought about your family,” she said, “before you decided to destroy everyone else’s.”

A knock came at the chamber door, sharp, authoritative.

Naomi didn’t look away from Prescott when she said, “Enter.”

The door opened, and two men in dark suits stepped in, earpieces visible, followed by a uniformed state trooper. The lead agent held up a badge.

“Judge Calvin Prescott,” he said. “I’m Special Agent Thomas Reynolds, Federal Bureau of Investigation. You are under arrest for racketeering, deprivation of rights under color of law, and wire fraud.”

Prescott looked up, eyes wet, searching Naomi’s face for the kind of mercy he had never offered anyone else. He found only truth.

Naomi stood aside, not triumphant, not gloating, just allowing the world to become what it had always been supposed to be.

“Stand up, Calvin,” she said quietly. “It’s time to face the music.”

News in Cedar Hollow traveled fast. Scandal traveled faster.

By the time the agents led Prescott out into the courthouse rotunda in handcuffs, the building vibrated with whispers. Lawyers paused mid-conversation. Defendants looked up from forms. Clerks leaned over desks like prairie dogs sensing a predator.

Naomi walked behind the agents, still in her hoodie and sweatpants, but the way she moved made the outfit look like armor. Prescott tried to pull his suit jacket over the cuffs. Agent Reynolds didn’t allow it. Prescott walked in his shirt sleeves, sweat stains blooming under his arms, eyes fixed on his shoes like he was praying the floor would open.

The crowd went silent as the group reached the center of the rotunda.

Naomi stopped.

The agents paused instinctively, as if they felt her authority without being told.

Naomi turned to face the room, voice carrying without a microphone, ringing against the marble.

“My name is Justice Naomi Caldwell of the United States Supreme Court,” she announced.

A collective gasp rippled through the crowd. Phones lifted. Cameras started recording.

“For too long,” Naomi continued, gesturing toward Prescott, “this building has been a place of fear. The man you called ‘Your Honor’ has dishonored this institution. He sold your rights for profit. He mocked the weak to please the strong.”

She swept her gaze across the front row, across the regular attorneys who had laughed with Prescott, who had traded silence for comfort.

“Do not think you are safe,” she said, and her eyes landed on Graham Hensley like a spotlight. “An audit is coming. If you participated, we will find you. If you stayed silent to protect your paycheck while the law was trampled, you are unfit to practice it.”

Hensley’s face turned the color of old paper. He looked for an exit, but state troopers had quietly positioned themselves by the doors.

Then Naomi looked at the people waiting, the mothers holding folders, the young men shifting nervously, the ones who had learned to expect pain from this building.

“To the citizens of Cedar Hollow,” Naomi said, her voice warming, “this is your courthouse. It belongs to you. When the law is broken by those sworn to uphold it, it is not a mistake. It is a crime.”

She nodded once to the agents.

“Take him.”

As Prescott was led toward the exit, a slow clap started. It came from the young woman with the parking ticket, the one whose tears had been treated like entertainment.

Then another person joined, then another, until the rotunda filled with applause. Not applause for cruelty, but relief. The sound of a boot lifting off a neck.

Prescott disappeared through the glass doors into the bright flash of news cameras outside.

Naomi didn’t follow.

She turned and looked directly at Deputy Larkin, who was pressed against a pillar trying to shrink into the paint.

“Deputy,” Naomi said.

Larkin jumped. “Yes, Justice.”

“You have two women downstairs,” Naomi said. “One named Becky. Another who goes by ‘Mama.’ Bring them here. Bring their paperwork.”

Ten minutes later, Becky emerged into the lobby blinking like someone dragged into sunlight after too long underground. The bruised woman followed, chin lifted in defiance even when she didn’t know what room she’d been brought into.

Becky spotted Naomi and hurried forward, confusion and hope tangling in her face.

“Naomi, what’s happening? I heard clapping… and—”

Naomi smiled gently. “The judge had to leave early. Sudden change in career.”

She took the paperwork from Larkin’s trembling hands, scanned it, then ripped it clean in half.

“You’re free to go,” Naomi said.

Becky’s mouth fell open. “But the bail… I don’t have—”

“There is no bail,” Naomi replied. “The charges were predicated on an unlawful order from a corrupt official. They are vacated.”

Becky started crying again, this time from shock, and she hugged Naomi like she had found ground after a flood.

Naomi patted her back, gaze lifting briefly to the empty bench upstairs that had once been Prescott’s throne.

The bruised woman stared at Naomi with something like awe. “You weren’t joking,” she muttered. “You really… you’re the hard karma.”

Naomi’s laugh was quiet, warm, and human. “Karma has no deadline,” she said. “But sometimes I like to expedite shipping.”

She handed Becky a simple business card.

“This is the number for my scholarship fund,” Naomi said. “We help young people unfairly impacted by the legal system get back into school. You call Monday. You tell them I sent you.”

Becky wiped her face with her sleeve, voice trembling. “Why would you help me?”

Naomi looked at her the way a lighthouse looks at the dark, not sentimental, just steady.

“Because the law isn’t supposed to break you,” she said. “It’s supposed to protect you. And when it fails, we rebuild.”

Outside, the afternoon sun hit the courthouse steps with clean brightness, as if the day itself had been holding its breath. A black sedan rolled up to the curb. A young man in a suit stepped out, opening the door with practiced efficiency.

“Justice Caldwell,” he said. “Your flight to Washington leaves in three hours. Confirmation hearings tomorrow.”

Naomi paused and looked back at the courthouse, the building that had once held her childhood memories and now held a fresh wound.

She pulled up the hood of her Myrtle Beach sweatshirt, not as camouflage now, but as a quiet statement: power didn’t require a costume.

“Let them wait,” she said, sliding into the car. “I want a cheeseburger first. Justice makes you hungry.”

But Cedar Hollow’s rot didn’t end with one judge.

As Prescott was processed at the very county jail he had helped fill, the shock wave tore through the town’s hidden power structures like a storm through cheap roofs. Graham Hensley drove his silver Mercedes ninety miles an hour toward his office, hands shaking, planning to shred files before anyone could look. At City Hall, Mayor Clint Gable sat with blinds drawn, watching footage of Prescott in cuffs on the news with a scotch in his hand that suddenly tasted like panic.

He called the police chief, voice sharp. “Tell me we have containment.”

“Sir,” the chief said weakly, “there’s a rumor. They say Justice Caldwell brought a forensic accountant. IRS, too.”

The words IRS drained the mayor faster than any FBI badge. The FBI hunted crimes. The IRS hunted money. And money, Mayor Gable knew, always left footprints.

“Go to the evidence locker,” he hissed. “The city planning hard drive. I need it to disappear. Flooding, electrical fire, I don’t care.”

“I can’t,” the chief whispered. “Turn on Channel Five.”

Gable flipped the TV, and his stomach fell through the floor.

There, live from Marcy’s Kitchen, sat Naomi Caldwell in her hoodie, eating a cheeseburger in a window booth like she owned the day. Across from her sat Jamal, newly released, thinner, eyes harder than they should’ve been at his age. Beside Jamal sat Arthur Phelps, the former city planner Gable had fired and tried to silence.

The reporter’s voice crackled with excitement. “We are receiving reports that Justice Caldwell is meeting with Arthur Phelps, who claims he has proof of a massive embezzlement and land seizure scheme involving City Hall…”

Gable dropped his phone. The scotch glass slipped from his hand and shattered on the floor.

She hadn’t just come for the judge.

She had come for the kingdom.

Inside Marcy’s Kitchen, the owner kept coffee flowing with hands that understood community better than any politician’s speech. Naomi listened as Arthur, nervous and sweating, opened a thick binder.

“Mayor Gable and Prescott had a deal,” Arthur explained. “Prescott would impose maximum fines on homeowners in the Fourth Street District for minor infractions. Uncut grass, peeling paint, cracked sidewalks. When families couldn’t pay, the city placed liens, then foreclosed.”

“And then,” Naomi prompted, voice calm.

“And then they sold the properties to Pine Ridge Holdings for pennies,” Arthur said. “Pine Ridge is owned by the mayor’s brother-in-law.”

Jamal slammed his fist on the table. “They stole our homes. They locked me up so they could steal Grandma’s house.”

Naomi covered Jamal’s hand with hers, grounding him.

“They used you,” she said quietly. “And hundreds of others. They created a story that the neighborhood was dangerous so they could drive prices down. They counted on you being invisible.”

Her gaze lifted, fierce.

“They forgot invisible people still have voices.”

The diner bell jingled.

Mayor Clint Gable walked in alone, shirt sleeves rolled, face drawn as if fear had aged him a decade in a morning. FBI agents at the counter straightened. Hands hovered near holsters.

Naomi didn’t look away from her fries. “Sit down,” she told the agents. “Let the mayor speak.”

Gable approached the booth like a man stepping toward a firing squad with paperwork in his pocket. “Justice Caldwell,” he rasped. “We need to talk. Prescott went rogue. I had no idea about the harsh sentences. I’m a victim of his deception too. I came to offer cooperation.”

Naomi set down her burger and dabbed her mouth with a napkin, each movement slow, deliberate, like she was giving him time to choose honesty before the world chose for him.

“Mr. Mayor,” she said, “do you know what federal conspiracy carries as a sentence? It’s not thirty days. It’s twenty years.”

Gable’s eyes flicked toward the door. Naomi’s voice cooled.

“Don’t,” she warned. “Don’t add resisting arrest. Show dignity for once.”

She nodded at Arthur. “Page forty-two.”

Arthur turned the binder around, hands trembling. A printed email stared up like a confession.

From: Mayor Clint Gable

To: Judge Calvin Prescott

Subject: Fourth Street problem

Body: Ramp up the fines. We need the Caldwell lot by November. If the old lady won’t sell, condemn it. Make her life hell.

Gable’s face drained until he looked like wax.

Naomi’s voice softened, but it was not kind. It was surgical.

“You targeted my mother’s property because you believed she was just an old Black woman who wouldn’t fight back.”

Agent Reynolds stepped forward. “We mirrored your server, Mayor. We have the emails, bank transfers, kickbacks.”

Gable sagged, arrogance collapsing into something small.

Reynolds pulled out handcuffs. “Clint Gable, you are under arrest.”

As the cuffs clicked, Jamal stood and stepped closer, eyes steady.

“My name is Jamal Turner,” he said. “I’m not a thug. I’m not a statistic. I’m a pre-med student. And I’m going to watch you go to prison.”

Gable looked down, unable to meet his eyes, and in that moment Cedar Hollow’s story shifted: the people who’d been treated like scenery became witnesses.

The case against Pine Ridge Holdings moved fast after that. The developer, slick and confident, tried to flee. The FBI met him at the tarmac. But Naomi’s true fight wasn’t just arrest. It was repair.

Months later, in federal court, Naomi filed an amicus brief arguing that money seized from the scheme should not disappear into government accounts while victims remained broken. She built the logic carefully, brick by brick: the wealth extracted from stolen equity must be returned to the community it was taken from. Restorative justice, not as a slogan, but as structure.

The courtroom was packed with families who had been evicted, including Becky, now wearing clean clothes and a brave expression that still trembled at the edges. On the bench sat a judge Naomi had mentored years earlier, Judge Elaine Olcott, stern and fair.

Judge Olcott read the brief in silence, then looked at the gallery, at the faces that had been treated like collateral damage.

“The court finds the logic irrefutable,” Judge Olcott ruled. “The seized assets are hereby placed into a trust for the reconstruction of the Fourth Street District. The government will not take a dime until every homeowner is made whole.”

The room erupted. Not just applause, but sobs. Not victory for its own sake, but the strange, holy relief of being seen.

A year later, Cedar Hollow’s courthouse looked the same from the outside. Brick. Columns. Old pride.

Inside, it felt different. Like someone had opened a window in a room that had been closed too long.

Calvin Prescott, no longer “Your Honor,” was inmate 9440 in a state penitentiary three counties over. His days of leather chairs were gone. He worked in laundry now, scrubbing stains from uniforms, learning the intimacy of other people’s dirt. His appeal was denied in a single sentence.

Back in Cedar Hollow, the empty lot on Fourth Street where Naomi’s mother’s shed had once stood was no longer an “eyesore” on a judge’s tongue. It had become the Caldwell Community Legal Center, a brick building with bright windows and free clinics, where people could walk in without fear that their poverty would be treated as guilt.

On an autumn afternoon, Naomi stood outside the new building beside Jamal, now thriving in college, carrying textbooks instead of shame. Becky stood nearby too, working at the front desk while taking paralegal classes at night.

“You did all this,” Jamal said, voice thick with awe. “You took down the whole system.”

Naomi shook her head gently, watching children play on the sidewalk where “blight” used to be a label like a curse.

“I didn’t take it down,” she said. “I reminded it what it was supposed to be.”

She looked at the bronze plaque by the door. It did not carry her name. It carried the names of the families who reclaimed their homes.

“Power doesn’t live in robes,” Naomi said quietly. “It lives in responsibility. In courage. In people refusing to be invisible.”

Becky hesitated, then asked, “Do you think it could happen again? Another judge like him?”

Naomi let out a warm, genuine laugh. “It could,” she admitted. “Which is why we don’t stop watching.”

She opened her car door, then paused, glancing back at the building one more time.

“And if another one forgets the Constitution,” she added, eyes bright with a calm promise, “we’ll remind him. Again.”

Because the most human ending wasn’t vengeance.

It was a town learning to breathe.

It was a young man returning to his studies instead of a cell.

It was a frightened girl discovering she had a future.

It was a courthouse becoming, at last, a house for the people.

And it was a Supreme Court justice proving that you could walk into a room wearing a hoodie and still carry the weight of the law, not to crush, but to protect.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load