The wind cut through the canyon like a wet blade, dragging the metallic bite of snow and the heavier copper tang of spilled blood down the rocks. Elias Hart tightened his collar and rode his mare, Juniper, along the rim with the slow caution of a man who had learned the mountains did not forgive impatience. From up here, the world was a brutal painting in winter whites and granite grays, and silence usually meant safety. Today the silence felt bruised, as if something had shouted and the echo had been buried under drifts.

Juniper huffed, uneasy, ears swiveling toward the ravine floor. Elias didn’t need tracks to know there had been a struggle. His eyes caught the wrong angles in the snow, the jagged geometry of wood where wood shouldn’t be, the faint dark stippling that no snowfall truly erased. He dismounted and guided her down the scree, stones clicking under iron shoes, until the canyon opened like a wound. The wagon lay shattered at the base of the cliff, canvas torn into ribbons that snapped in the gale. Bodies were scattered in the drifts, half claimed by white, their shapes already rounding into the anonymous lumps the mountains preferred.

He moved among them with a grim steadiness, boot-crunch loud in the hush. A quick glance at the broken harness told him the team had bolted, or been cut loose, or died somewhere out of sight. The men were dressed like escorts, not farmers, and their weapons were better than the sort carried by desperate prospectors. Elias checked for pulses he didn’t expect to find, because that was the duty the frontier demanded: you looked anyway, even when hope was a foolish luxury. The frost on the wagon’s splintered ribs told him this had happened at least two days ago, maybe more, and whatever had done it had done it fast and without mercy.

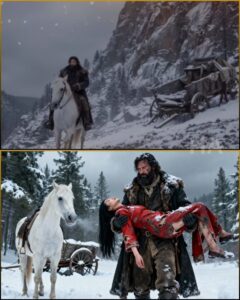

He was about to turn back, to leave the dead for spring and say a prayer he didn’t fully believe in anymore, when a flash of color stabbed through the gray world. It wasn’t the healthy red of life, not out here in January. It was too vivid, too wrong, the kind of crimson that belonged in a parlor, on a stage, or in a story someone told by firelight. Elias followed it toward the overturned carriage bed, where a broken axle created a shallow pocket in the snow.

A woman lay there, sheltered by wreckage like the mountain had tried, belatedly, to hide her. She was dressed for no territory Elias had ever known. A long silk gown clung to her in stiff folds, red embroidered with gold thread that caught even the flat winter light and refused to dim. Her skin was pale as old ivory, her lips tinged blue, and her black hair spilled across the snow like ink poured from a jar. For a moment Elias simply stared, because the brain resisted understanding when reality made such an extravagant mistake.

Then instinct snapped him back into motion. He pulled off his glove and pressed two fingers to her throat. Her skin was ice, frighteningly cold, but beneath it a faint flutter argued against death. Alive. Barely. Elias didn’t waste breath on questions the canyon wouldn’t answer. He stripped off his heavy coat and wrapped her in it, then lifted her with care that felt almost clumsy in his big, scarred hands. She weighed less than she should have, light in the terrifying way of someone whose body had already started surrendering. Her head lolled against his chest, and he felt the brittle fragility of her breathing.

“Easy now,” he murmured, voice rough from disuse, speaking into wind that didn’t care. “I’ve got you.” It was a promise made as much to himself as to her.

He mounted Juniper with the woman cradled across the saddle, urged the mare into a careful trot, and set a hard pace toward timberline. The sky was darkening to a bruised purple in the west. Elias knew that color. It meant storm, the kind that erased trails and turned distance into a death sentence. His cabin sat miles away, tucked into lodgepole pine, a stubborn box of hand-hewn logs he’d built after deciding solitude was safer than love. Now he rode as if pursued, because in his bones he understood something else: whoever had slaughtered that wagon hadn’t done it for sport.

The ride became a battle against night. The temperature dropped fast, and the wind rose to a howl that stripped heat from skin in seconds. Elias kept one arm clamped around the woman’s middle, feeling the alarming stillness of her body. She didn’t shiver, and that frightened him more than panic would have. He’d seen calves freeze standing up, eyes dull with that same quiet surrender, and he refused to let the same thing happen to her. When Juniper finally cleared the last ridge and Elias saw the squat shape of his cabin in the trees, a hard knot in his chest loosened, only to tighten again with urgency.

He didn’t bother with the barn. He left Juniper in the lee of the structure with a muttered promise of oats and care later, then kicked open the cabin door with his boot. The inside smelled of smoke, pine resin, and dried sage. It was dark, simple, and built for one man’s needs. Elias carried the woman to the hearth, laid her on the bearskin rug, and worked the coals back to life. Fire caught, licking up with hungry light, throwing shadows across the rough walls.

In the glow, the strangeness of her became sharper. Her gown wasn’t just fine; it was impossibly fine, silk so smooth it looked like poured water, stitched with birds and flowers and a coiling dragon that seemed almost alive. The hem was torn and stained with mud, but even ruined it radiated wealth. It made Elias’s floorboards look poorer by comparison. He filled the kettle and hung it, then knelt to remove her shoes: delicate embroidered slippers soaked through. His hands looked monstrous against her narrow feet, and when he rubbed her toes to force circulation back, he hated how waxy they felt.

He moved with the practiced efficiency of someone who had mended fences in blizzards and stitched his own wounds with a needle and whiskey. Yet this felt different. A calf either lived or died, brutally simple. A person carried stories inside them, and he could already feel the weight of hers pressing into his quiet life. He warmed water and cleaned the grime from her face. She was beautiful in a way that didn’t belong to the mountains, high cheekbones and a mouth too soft for a hard country. A bruise darkened her temple, likely from the crash. Elias found a thick wool blanket and draped it over her, then sat back on his heels and watched her chest rise and fall like the smallest argument against the cold.

The wind rattled the latch, trying to remind him how close death had come to his door. For the first time in years, the cabin felt crowded. Elias had once cherished silence like a shield. Now it felt like a question with no polite answer.

Who was she? Why was a woman dressed like royalty traveling through the worst pass in Colorado in the dead of winter? And who had wanted her dead badly enough to slaughter armed men and leave her to wolves?

He fed the fire through the night, because guilt was easier to bear when his hands were busy. Sometime near dawn, a sharp intake of breath broke the stillness. Elias looked up from the harness he’d been mending and saw her eyes open, dark and wild, darting around the room like a trapped bird. She scrambled backward until her shoulders hit the hearth stones, clutching the blanket under her chin as if it could become armor. Words spilled from her mouth in a language Elias didn’t know, musical and frantic, the sound of panic shaped into syllables.

He set the leather down slowly and raised his empty hands. He spoke the way he spoke to spooked horses, low and steady, because tone mattered even when words failed. “Easy. You’re safe here. No one’s going to hurt you.” She didn’t understand the sentences, but she understood his posture. Her gaze locked on him and assessed him with sharp fear: his size, his beard, the gun belt hanging on a peg by the door. A man alone in a cabin with a weapon wasn’t a comfort in any language.

Elias moved to the stove, ladled broth into a tin cup, and set it on the floor between them. Then he backed away and sat in his chair. “Eat,” he said, miming the motion with exaggerated patience. He watched her decide, because survival always required a decision. Slowly, hunger outvoted fear. She crawled forward, the ruined silk rustling softly, and took the cup with hands that trembled despite the warmth. She drank too fast at first, coughed, then forced herself to slow down, as if discipline was a rope she could grab even in chaos.

When she finished, she placed the cup down carefully and looked at him as though measuring a debt. “Thank you,” she whispered in English, heavy-accented, the words shaped like they’d been learned from paper rather than people. Elias nodded once, throat tight with the strange relief of hearing a language he could answer.

“I’m Elias,” he said, tapping his chest.

She hesitated, eyes flicking to the window where snow climbed the glass like a threat. Whatever name she carried, it carried danger too. Finally she lowered her gaze. “Meilin,” she said softly.

Outside, the storm howled harder, sealing them into the same small room. Two strangers from different worlds, bound by the oldest bargain there was: live through the night first, ask questions later.

Recovery came in increments so small they were almost invisible. For two days Meilin barely moved from the hearth, sleeping for hours while her body fought to reclaim itself from the cold. Elias went about his routines, chopping wood, checking trap lines near the creek, tending Juniper, but he was always aware of the presence inside his cabin. The space he’d built for solitude started to change around her like a room rearranged by unseen hands. He found himself closing the door quietly instead of letting it slam. When he stamped snow from his boots, he did it with care, as if loudness might frighten her back into that corner of the hearth.

They spoke little at first because language was a wall, but necessity built a gate. Elias learned she preferred tea to coffee, wrinkling her nose at the bitter brew as if insulted by it. He found a tin of dried mint he’d been saving and brewed that, and when she smiled for the first time, it was small but startling, a crack in the mask that made his chest feel oddly warm. Meilin watched him with guarded intensity, studying his hands, his tools, the patterns of his day as if understanding him might keep her alive. Elias didn’t like being studied, but he understood it. People who survived ambushes learned to read rooms quickly.

On the third afternoon her fever finally broke. Elias came in from the barn to find her sitting up, staring at the red gown draped over a chair to dry. She held the fabric with reverence, tracing the jagged tear that ran from knee to hip. To Elias it looked like ruined finery, useless against winter. To her it was something else entirely, something she couldn’t afford to lose. She mimed sewing, then pointed at the tear and looked at him with a stubborn kind of hope.

Elias hesitated because his repair kit was meant for canvas and leather, not silk. He retrieved a battered tin box from under his bunk and opened it. Inside were heavy needles, thick thread, and sinew, the tools of a man who fixed rough things. He set it before her, feeling a strange embarrassment about the coarseness of his world.

Meilin examined the needle like it was a nail. She looked at the delicate silk, then back at the needle, and for a heartbeat Elias expected tears. Instead she nodded with pragmatic acceptance that surprised him. She sat by the window to steal the fading light and began to work, slow and painstaking. When the thread was too thick, she unpicked strands with her teeth and nails, splitting it down until it could pass through silk without ripping it apart. Elias watched from the table while he oiled his rifle, and the longer he watched, the clearer it became that she wasn’t merely mending cloth.

She was reclaiming herself.

By the time the storm eased and the world outside turned blinding white, a fragile rhythm had formed between them. The dress was repaired, though the black stitches stood out like scars against red. Meilin wore it anyway with a dignity that made the damage seem irrelevant. She refused to be idle. She couldn’t chop wood or haul water yet, but she took over what she could: sweeping the floor with meticulous care, stacking tins in the pantry in a logic Elias didn’t understand. It was as if she needed order around her because the past was too chaotic to hold.

One evening Elias sat whittling a new axe handle, and he felt her watching him. He looked up and found her holding a bowl of stew she’d heated, adding dried herbs he rarely used. The smell was richer than his usual plain fare, and when he took a bite, he tasted something unfamiliar: not just flavor, but attention. He set the spoon down, surprised by how much it mattered.

“You have strong hands,” Meilin said, struggling with the words, pointing to his carving.

Elias glanced down at his hands, scarred and thick, knuckles swollen from years of wrestling land into obedience. “They work,” he answered simply, because he’d never been good at poetry.

Her gaze shifted to the window, where the snow piled like a wall. There was fear there, but also calculation, the look of someone who understood that danger didn’t vanish just because it wasn’t visible. Elias chose his next words carefully. “The men in the wagon,” he said, stepping into the territory of the past. “They weren’t just drivers.”

Meilin went still. Her eyes dropped to her folded hands. “No,” she said softly. “Guardians.” The word landed like a stone. She looked up, and for a moment the mask slipped, revealing sorrow so deep Elias almost looked away out of instinctive respect. “They die for me,” she added, each word slow and deliberate, as if she were forcing her tongue to carry weight.

The sentence hung between them, heavy as a door barred from the outside. Elias realized then that he hadn’t rescued a traveler. He had pulled the center of a storm into his cabin, and the mountains, kind as they could be, were not kind enough to hide storms forever.

He nodded once, offering the only comfort he knew how to give. “The snow covers tracks,” he said. “No one finds this place until thaw.”

Meilin studied his face as though searching for lies. Finding none, she exhaled, long and shaking. “Until thaw,” she repeated, and in her voice Elias heard what that promise truly was: not a solution, just a reprieve. In the high country, reprieves were the closest thing to mercy.

Weeks slid into a month, the days bleeding together in the hypnotic rhythm of survival. The cabin that had once been Elias’s quiet fortress became a shared vessel navigating the vast winter. Meilin grew stronger, venturing outside wrapped in Elias’s spare coat that swallowed her frame, the red of her gown flashing beneath like a secret wound against the snow. She watched Elias work with intensity that made him uneasy at first, then strangely proud, as if he had something worth learning.

One night after supper, she sat at the table with a piece of charcoal and the back of an old supply ledger. She began to draw not a picture but a column of intricate characters, strokes like falling rain frozen midair. Elias watched the grace of her hand, soot staining her fingers, and felt the distance between their worlds in the smallest movements.

“What is it?” he asked.

“A poem,” she said, her English improving with daily necessity. She tapped the characters lightly. “From my home. It says… ‘The mountain does not bow to the wind.’”

The words felt like they belonged here, in this cabin battered by storms. Meilin’s gaze lifted, dark and steady. “My father,” she continued slowly, choosing each word as if it could cut her, “is powerful. He promised me to a general. A man who conquers.”

Her hand tightened around the charcoal until it snapped. She stared at the broken piece, jaw set. “I did not wish… to be conquered.”

Elias understood the shape of that sentence even if he didn’t understand the politics behind it. He’d grown up watching men claim land, claim cattle, claim women, as if the world were a ledger and everything could be listed and owned. He’d run from towns and expectations and the kind of loneliness that followed him no matter how far he rode. In that moment, he recognized a familiar cage, just built from different materials.

He reached across the table and covered her soot-stained hand with his rough palm. “You aren’t property,” he said, voice low and hard as iron. “Not here.”

Meilin didn’t pull away. Instead she turned her hand and interlaced her slender fingers with his, a quiet pact forged in firelight. Elias felt something inside him shift, subtle but irreversible, like ice beginning to crack on a river that had held firm all winter.

The false spring arrived with treacherous beauty, sun melting drifts by day only for them to freeze into glass at night. It was on one of those bright afternoons that the isolation broke. Elias was at the corral, chopping ice from the trough, when Juniper’s ears pinned back and she let out a low warning snort. Elias froze, hand dropping to the revolver at his hip, and scanned the tree line.

A rider emerged from the pines, a silhouette cut from shadow against snow glare. The horse was black and high-stepping, and the man on its back sat with a posture that belonged to city streets and paid violence. He wore a long gray duster and a flat-brim hat that hid his eyes. He didn’t look like a prospector or a preacher. He looked like a man who always knew where his prey would run.

Elias didn’t look back at the cabin, though every nerve begged him to. He prayed Meilin had seen the approach and followed the plan they’d spoken about in gestures: hide, stay silent, trust him. Elias walked to the gate and leaned casually against the post, pretending he didn’t feel his pulse in his throat.

The rider stopped ten yards out. He was handsome in a sharp, reptilian way, face smooth, eyes pale as winter sky when he tilted his head. “Afternoon,” he said politely, voice carrying a hint of the South. “You’re a hard man to find.”

“I’m not lost,” Elias replied.

The stranger chuckled, dry as dead leaves. “No. But something else is.” He leaned forward, gloved hands resting on the saddle horn. “I’m looking for a wagon, and a passenger. Young woman. Dressed… unusually.”

Elias held his gaze, face blank with practiced frontier indifference. “Found a wagon in the ravine two weeks back,” he lied smoothly, mixing truth with omission. “Smashed to kindling. Wolves had been at the bodies. Didn’t see any woman.”

The stranger’s smile didn’t move, but his eyes hardened. He glanced past Elias toward the cabin, where smoke curled from the chimney in a thin, innocent line. “Wolves,” he repeated softly. “They’re thorough creatures. They usually leave bones.”

He straightened, gathered his reins. “Name’s Cole Graves,” he said. “I’ll be camped down by the creek. If you remember anything, there’s a reward. Gold enough to buy this whole mountain.”

Elias watched him ride away into the trees as the sun sank behind peaks. Graves hadn’t bought the lie, and Elias knew it. Men like that didn’t travel this far for rumors. They traveled for certainty, and their patience was a weapon.

Elias bolted the cabin door behind him and found Meilin in the kitchen shadows clutching a paring knife, knuckles white. Her eyes were fixed on him with a question that didn’t need language.

“He knows,” Elias said, stripping off his coat. He went to the gun rack and took down the Winchester, checked the brass cartridges, then set the rifle within reach. “He’s waiting for dark.”

Meilin stepped forward, fear hardening into something brittle and fierce. “I can go,” she whispered. “If I go… he leaves you.”

The thought of her walking out into the snow to surrender made Elias’s chest ache with a sharp, physical pain he hadn’t expected. He crossed the room and took her shoulders gently, forcing her to look at him. “No,” he said. “We don’t trade people like cattle. We hold the door.”

Night fell like a hammer, extinguishing the world outside. Elias put out the lantern, leaving only the dying embers to cast a dull red glow. He positioned himself by the window, shutter cracked an inch, rifle resting on the sill. Meilin sat on the floor beneath it, out of line of fire, breathing slow and controlled. Hours crawled. Wind picked up, whistling through the log seams and masking sound. That was what frightened Elias most: the mountains could hide predators as easily as they hid prey.

The first strike came as glass shattered in the bedroom. Not a bullet, but a firebrand, a rag soaked in kerosene wrapped around a stone. It landed on the quilt, flames licking hungrily at dry fabric. Elias spun, shouting for Meilin to stay down, but she was already moving. She grabbed a heavy wool rug and smothered the fire with desperate precision, stomping until smoke coughed into the room.

At the same moment, the front door shuddered under a massive impact.

Elias didn’t hesitate. He fired through the wood, Winchester booming in the small cabin. A shout of pain came from outside, followed by two rapid shots that splintered the frame, sending showers of wood inward. Graves wasn’t waiting anymore. Elias racked the lever, jaw clenched, mind coldly clear. He knew Graves wouldn’t be alone in intent even if he was alone in body; men like that always had angles, always had backup plans in their heads.

The door burst inward, lock shattered. Graves stood framed in moonlight, revolver in each hand, face calm as if entering a parlor. Elias dropped to one knee and fired upward. The bullet caught Graves in the chest and knocked him backward into the snow with a grunt that sounded more surprised than pained. Silence crashed down, ringing in Elias’s ears. He stood, rifle trained on the doorway, and moved outside into cold so sharp it felt like punishment.

Graves lay on his back, breath bubbling wet and shallow. Up close, his politeness was gone, replaced by disbelief that a lonely rancher had proved harder than expected. He tried to speak, but his lungs refused him. His eyes found Elias’s, then drifted, and whatever darkness he carried slipped back into the night without ceremony.

Elias stood over him until the adrenaline drained into grim exhaustion. Then he felt a hand on his arm. Meilin had come out, shivering in the snow, staring down at the dead man. She didn’t scream or look away. She simply watched, then lifted her gaze to Elias and nodded once, an acceptance of the violence required to stay alive. It wasn’t gratitude. It was understanding, the kind forged in blood.

They buried Graves at first light beyond the tree line, hard ground resisting the shovel until Elias used a pick. He marked the grave with a cairn of stones, not out of respect but necessity. Evidence drew attention. Attention drew men like Graves, and Elias had no interest in becoming the next story the mountains swallowed. When they returned to the cabin, the air felt cleaner, as if some invisible cord had snapped.

It should have ended there, but danger rarely ended cleanly. That afternoon, while Meilin slept, Elias searched Graves’s coat for anything that might explain how he’d found them. In the inside pocket he found a folded paper sealed with red wax stamped with a dragon. The symbol wasn’t just decoration. It carried authority, the kind that crossed oceans. Beneath it was a second thing: a small photograph of Meilin taken in a setting far too elegant for the frontier, her hair arranged with jeweled pins, her expression composed in the way of someone trained to hide emotion. On the back, in careful English, someone had written: RETURN HER QUIETLY. DO NOT LET LOCAL AUTHORITIES INTERFERE.

Elias stared at the words until they blurred into something worse than fear. This wasn’t a local feud. This was bigger than a canyon ambush.

When Meilin woke, Elias sat her at the table and placed the seal and photograph before her. Her face went still, then pale, then hard. For a long moment she said nothing, and Elias realized she was deciding whether truth would save him or doom him. Finally she reached into the trunk where she kept her few possessions and pulled out a pendant wrapped in cloth: jade carved into a phoenix, cool and flawless, the kind of treasure that shouldn’t exist in a cabin built from logs.

She set it on the table. “Meilin,” she said softly, then shook her head. Her voice grew steadier. “Not full truth.”

Elias waited, because pushing would only make her retreat.

“My name,” she said, “is Zhao Meilin.” She swallowed, and when she spoke again, the words carried the weight of a life she’d been trained for. “In my home… I am called princess. Not big like stories, but bloodline. My father is… a prince in the court. Powerful enough to buy men like Graves.”

Elias felt the room tilt slightly. A princess in his cabin sounded ridiculous, like a penny novel, except the dragon seal on the table was very real, and so were the bodies in the ravine.

Meilin’s gaze fixed on the fire. “A general wanted me,” she said, voice tight. “My father promised to keep peace. I ran. I took papers… proof of things the general did. Killing. Stealing. If those papers reach the wrong hands, many die. If they do not reach the right hands… I die anyway.”

Elias’s mind moved through cause and effect like it always had when weather threatened livestock: if this, then that. If she carried proof, the massacre made sense. Kill the guards, retrieve the papers, leave her to freeze, and no one asks questions because the mountains had done the killing. It was efficient cruelty, the kind power preferred.

“Where are the papers?” Elias asked quietly.

Meilin touched the lining of her coat, then looked at him with a sadness that felt older than her face. “Gone,” she admitted. “In crash. Or taken.”

Elias exhaled slowly. Losing the papers meant she was still hunted, not for what she held, but for what she knew. That was worse in some ways, because knowledge could not be retrieved from the snow.

Spring came in earnest, the valley turning green with a violence of color that felt like a miracle. The creek roared with meltwater, and the air smelled of wet earth and pine resin. Elias and Meilin repaired fence lines together, work becoming a language they both spoke fluently: lift, hold, tie, nod. Meilin swapped silk for flannel, rolled sleeves on shirts too large for her, and braided her hair back with practical severity. She looked less like a rescued ghost and more like someone choosing a new shape for her life.

One day a small crew of Chinese railroad workers passed through the lower valley, heading toward a camp where tracks were being laid. Elias watched their faces register surprise at seeing Meilin, then watched Meilin’s posture change, straighten, her expression turning careful and regal in a way that made his skin prickle. She spoke to them in rapid Chinese, and their eyes widened, then softened with something that looked like relief. When they left, one of them bowed slightly, a gesture subtle but unmistakable, as if he were acknowledging more than a traveler.

That night Meilin sat by the window and wrote characters on paper with ink Elias had never bothered to use before. “Letter,” she explained. “To San Francisco. To people who can hide me.” She paused, then added, “But hiding is not living.”

Elias understood that too well. He’d built his cabin as a hiding place from grief after losing his wife to fever in town, from the way people looked at a man who couldn’t save what mattered. Solitude had been his answer because it required nothing. Meilin’s presence had quietly proven that survival wasn’t the same as living.

A week later, a sheriff rode up with two deputies, claiming they were checking on rumors of a dead man near the creek. Elias kept his face calm while his stomach tightened. Rumors traveled faster in spring, carried by meltwater and gossip. Graves’s disappearance would invite questions, and questions were the teeth of the world beyond the mountains.

Meilin stepped onto the porch beside Elias, shoulders squared. She didn’t wear silk. She wore flannel and leather gloves, but her gaze held the sheriff’s the way a queen might hold a courtier. When the sheriff’s eyes flicked toward the cabin, Elias saw calculation. The law could be bought. Graves had proven that. Elias made a choice then, clear as a snapped rein: he would not hand her over to men who treated humans like rewards.

“She’s under my roof,” Elias said, voice steady. “She stays.”

The sheriff opened his mouth, likely to talk about jurisdiction, about trouble, about what a man owed the law. Meilin interrupted gently, her English slow but sharp. “If you take me,” she said, “men will come. Not two. Not ten. They will burn your town to be quiet.” She let the implication hang, not as a threat but as a warning shaped like truth. “If you leave me,” she added, “no one knows I am here. And nothing happens to your people.”

The sheriff stared at her, unnerved not by her words but by the calm certainty behind them. Elias watched the moment the man’s courage fought his caution and lost. The sheriff tipped his hat with stiff politeness and turned his horse away, deputies following like shadows. When they were gone, Elias realized his hands were shaking. Meilin touched his wrist lightly, grounding him.

“You are not alone now,” she said.

Neither of them said love, because love was a dangerous word that made promises the world tried to break. Instead they built something sturdier. They turned Elias’s cabin into a place that didn’t just survive winter but welcomed it. They repaired the barn properly, planted a small garden, and cleared a room for travelers who got caught in storms the way Meilin had. When a lost boy stumbled down from the ridge one evening, half-starved and terrified, Meilin fed him without hesitation and Elias showed him where to sleep. When a railroad worker arrived with frostbitten fingers, Elias warmed him and Meilin wrapped his hands with careful skill learned from palace healers. Their home became a quiet refusal of the frontier’s cruelty, one small light in a landscape that loved to swallow people whole.

On the first warm day of real summer, Meilin opened her trunk and lifted the red dress. It was clean now, mended, beautiful enough to make the cabin seem rough again. She ran her thumb over the gold dragon embroidery for a long time, eyes distant. Elias didn’t speak, because some grief required silence as respect.

Finally Meilin folded the dress carefully and turned it inside out, hiding the dragon, hiding the loudness of what she had been. She placed it at the bottom of the trunk like a sleeping creature. Then she pulled on a flannel shirt, buttoned it with steady fingers, and stepped outside into sunlight.

She turned back to Elias, chin lifted, eyes clear. “I was Zhao Meilin,” she said softly. “I am… Meilin Hart, if you will have me.”

Elias felt emotion rise, fierce and unfamiliar, and he swallowed it down because tears were hard and he’d once believed he’d used up all of them. He simply nodded, because nods could carry vows without breaking under their weight. Meilin smiled, genuine and unguarded, and in that smile Elias saw not a princess hidden from hunters, not a survivor pulled from blood-stained snow, but a woman choosing her own life in a place that had tried to kill her.

Above them, a hawk circled in the clear blue sky, and the mountains stood unmoved, proud and indifferent. Yet in a small cabin tucked among pines, something had changed. Not the world, not the violence that still roamed it, but the meaning of one lonely man’s home.

It was no longer a hiding place.

It was a refuge.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load