The Montana Territory did not bother with politeness. It had no patience for people who wanted life to be gentle, or fair, or simple. Montana was wind that stole your breath, winters that bit through bone, and miles of open country where a single rider could disappear like a thought the moment you blinked. It was a place where a man could become a legend or become a grave marker, and sometimes the difference between the two was nothing more than one bad choice made in the dark.

The Blackwood Ranch sat outside a speck of a town called Copper Creek, an hour’s hard ride from the station and a world away from anything that could be called “civilized.” Ten thousand acres of cattle land stretched in every direction, framed by distant mountains and stitched together by barbed wire, creekbeds, and the kind of stubborn ambition that only survived in men who had already buried too many friends.

The four Blackwood brothers were those men.

They had the land. They had three thousand head of cattle. They had a barn that could swallow a storm and a bank account that kept the wolves at bay. But the ranch house itself, for all its size, felt hollow. It breathed cold at night, its rooms echoing with bootsteps and quiet that pressed down like a hand on the throat. Four men living together without softness, without laughter, without the ordinary rhythms that made a home a home, turned even a kingdom into a kind of exile.

The wind rattled the loose boards of the porch as William Blackwood slammed his palm on the kitchen table. The oak was thick and scarred from years of knives, cups, and arguments, but it still shuddered under the impact. William, at thirty-two, looked like someone Montana had tried to kill and failed. He was tall, broad-shouldered, bearded, with a long, pale scar near his jaw that made his face permanently severe.

“We are dying out here,” he growled, staring at his brothers like he expected them to argue back.

James Blackwood, second born and permanently amused by his own life, leaned back in his chair and spun a silver dollar across his knuckles. He had the kind of handsome face that made trouble look like an invitation, and his grin was a weapon he used as easily as his fists.

“Speak for yourself, Will,” James drawled. “I find the silence peaceful. Less nagging.”

“It ain’t about nagging,” Henry cut in.

Henry was twenty-eight, the one who fixed what broke and built what didn’t exist yet. His hands could repair a wagon wheel or stitch a wound without hesitation. Quiet did not mean weak, but it did mean lonely, and Henry’s eyes held that loneliness the way a deep well held water. He nodded toward the window, toward the land their father had died for.

“It’s about legacy. Pa didn’t fight the Sioux and the Winters just so the Blackwood name could die with four bachelors.”

Thomas, the youngest, only twenty-two, kept his eyes on his boots. He missed their mother the most. He missed the warmth of hands that touched your hair when you were sick, the way a house smelled when it was cared for, the simple comfort of a voice that didn’t sound like command or curse.

William’s jaw worked as if he were chewing on something bitter. Then he reached into his vest and pulled out a crumpled piece of paper. He didn’t unfold it at first. He just held it there, like an accusation.

“I’ve made a decision,” he said.

James stopped spinning the coin. The change in William’s tone was a warning all by itself.

“I wrote to a matrimonial newspaper in Boston. Placed an advertisement.”

Henry’s brows rose slowly. Thomas looked up, startled.

“Not just for me,” William continued, “for all of us.”

James pushed back from the table, disbelief flashing sharp as sunlight. “You did what?”

“I ordered us wives,” William said, as if he’d announced he’d ordered nails or flour. “Respectable women. Women willing to work. Women who want a new life.”

“You can’t just order a wife like a sack of flour,” James protested, but the outrage in his voice was tangled with something else. Fear, maybe. Or the realization that William was serious enough to do insane things.

“It’s done,” William said, and tossed four separate letters onto the table.

The silence changed texture. It became electric, as if the air itself held its breath.

Thomas reached for one envelope with careful fingers, as if it might burn him. The handwriting was elegant, looping, and faintly scented with lavender.

“Alice,” Thomas whispered after reading the first line. His voice softened without permission. “She likes poetry. Says she doesn’t mind the… the hardship.”

Henry opened his with a quiet, reverent precision. “Sarah,” he murmured, and his eyes lingered on the words longer than they needed to. “She says she’s strong. That she raised her siblings after their parents died.”

James snatched his letter like he meant to prove it wrong, ripping it open with skepticism. “Elizabeth,” he read aloud, scanning. “Sharp tongue, by the looks of it. She asks more questions about town and whether there’s a library than she asks about me.”

William held his own letter unopened for a moment. He already knew the name. He had exchanged three letters with her, each one direct and stripped of sentimental nonsense.

Mary.

She wanted safety. William wanted order. It had felt like business, a transaction, a solution to an empty house and a dying name.

“They arrive in three weeks,” William said finally, opening the letter and reading just enough to confirm what he already knew. Then he looked up, eyes hard. “We have that long to make this house fit for human habitation. If these women turn around and get back on the train, I will skin every single one of you.”

James snorted. “Charming speech. That’ll woo ‘em.”

William’s gaze sharpened. “This is not a game.”

Henry glanced down at his own letter again, as if to remind himself there was now a real person on the other side of these words. Thomas swallowed and nodded, already imagining a girl with blonde curls and frightened eyes stepping into their brutal world.

None of them, not even William, understood that three thousand miles away, in a cramped boarding house in Boston, four women were making a decision that would shape not only their lives, but their deaths, if they chose wrong.

The boarding house smelled of boiled cabbage and old wallpaper. The room the Davenport sisters rented was small and dim, the window only opening a crack, as if even fresh air cost money. Outside, the city pressed close, brick and soot and noise, but inside that room there was a tighter kind of pressure. Fear didn’t need space to breathe. It made its own.

Mary Davenport stood by the window, watching the street below through a slit in the curtain. At twenty-six, she carried herself like someone who had stopped believing the world would be kind and started believing she could survive it anyway. Her dark hair was pulled into a severe bun, but a few curls escaped, stubborn as hope.

“Did you mail them?” she asked without turning.

Elizabeth, twenty-four, sat on the bed polishing her spectacles with a corner of her dress. Sarah, twenty-two, folded clothing with sharp, angry movements, as if she could press the fear out of the fabric. Alice, nineteen, wept quietly into a handkerchief, trying not to make sound like crying could summon disaster.

“They’re mailed,” Elizabeth said, voice steady but tight. “But Mary… this is madness. Four brothers. Same ranch. What are the odds? What if they’re monsters?”

Sarah’s head snapped up, eyes blazing. “Better monsters we don’t know than the monster we do.”

At the word monster, Alice’s sob caught in her throat, and she stared at the floor like she could see blood in the wood grain.

Mary turned from the window at last. Her face looked composed, but her hands trembled slightly when she clasped them together.

“If Thaddeus Thorne finds us,” Sarah continued, voice dropping lower, sharper, “we won’t just be married off against our wills. We’ll be dead. Or worse.”

The name itself felt like a chain. Thaddeus Thorne. A man who collected debts the way other men collected trophies, with a smile that never reached his eyes and a ledger that might as well have been a death sentence. Their father’s debts had become a noose, and Thorne had decided the Davenport sisters were the payment.

“We have no choice,” Mary said. “Father’s debts are not ours to pay, but Thorne doesn’t care. He wants the Davenport women as trophies to settle his pride. We have to vanish. The West is the only place big enough to hide four women with no money and a price on their heads.”

“But to lie to them,” Alice whispered, voice broken. “To marry men we’ve never met… to pretend we’re strangers…”

“That is the most important part,” Mary said, and crossed the room to kneel in front of Alice. She took Alice’s cold hands in her own, forcing her sister to look at her. “Listen to me. We cannot let them know we are sisters. Not at first. If four women arrive together and act like a pack, those men will think we’re scheming. They’ll think we’re swindlers. We have to be four individual brides who coincidentally arrived on the same train.”

Elizabeth’s throat worked, as if she tasted the danger. “It’s a wicked game.”

“It’s a game for our lives,” Mary replied. Then she looked at each sister in turn. “Dry your eyes. We are not the Davenport sisters anymore. We are four strangers seeking love.”

Sarah let out a rough laugh that held no humor. “God help them if they aren’t what they promised.”

Mary’s gaze turned toward the window again, toward the city and the shadow she was leaving behind. “God help us if they are.”

They packed what little they owned into four battered trunks. Each item they folded and tucked away felt like a severed piece of their old life. By the time dawn came, their room looked stripped, as if they had never existed there at all.

And in a way, they hadn’t. Because by noon they would board a train and begin becoming someone else.

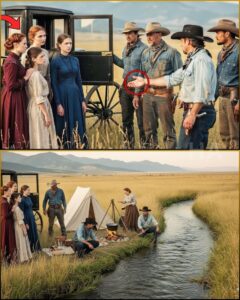

The Union Pacific steam engine screamed as it rolled into Copper Creek Station in early June, belching black smoke into a sky so blue it looked painted. Wildflowers bloomed across the valley, careless and bright, but the four Blackwood brothers noticed none of it.

They stood on the platform in their Sunday best, collars stiff enough to choke, boots polished until they shone, hats brushed clean of dust. They looked like men about to be judged.

James tugged at his tie with irritation. “I’m sweating like a sinner in church.”

“This is a mistake,” he muttered. “I’m telling you, Will, I’m going to turn around and walk away.”

“You move one inch and I’ll break your legs,” William said through his teeth. “Stand still.”

Henry stood with hands clasped behind his back, trying to look calm while his stomach twisted itself into knots. Thomas swallowed so hard it hurt and kept glancing at the train door like it might open onto an entirely different future.

The conductor stepped down and placed a yellow stool on the dirt. “Copper Creek,” he called. “End of the line for passengers.”

The door to the second car opened.

A hush fell over the platform.

The first woman to emerge wore a navy traveling dress and carried herself like a soldier. She was tall, her posture straight, her gaze scanning the station with careful precision. When her eyes found William, she didn’t smile. She simply nodded, as if acknowledging a contract.

Mary.

Behind her came a woman with auburn hair and spectacles, clutching a book to her chest as if it were armor.

Elizabeth.

She stepped down gingerly, eyes flicking over the mud with mild distaste before they found James. She raised one brow, unimpressed by his roguish grin.

Then came Sarah, almost leaping off the step before the conductor could help. Her brown dress looked practical, ready for work. She spotted Henry and smiled wide and genuine, the kind of smile that made his face heat like he’d stepped too close to a fire.

Finally, Alice appeared. Blonde curls framed a pale face, and fear lived openly in her eyes. She stumbled slightly, and Thomas instinctively stepped forward.

For a moment, the four women stood in a line. The four men stood opposite them. The tension between them was thick enough to cut with a Bowie knife.

William cleared his throat and stepped forward, voice controlled. “Miss Smith?”

Mary’s mouth tightened, but she held the lie steady. “Mr. Blackwood.”

William gestured stiffly down the line. “These are my brothers. James. Henry. Thomas.”

Mary turned toward the other women and smiled politely, feigning surprise. “It appears we are all destined for the same ranch. A fortunate coincidence.”

Elizabeth played her part flawlessly. “Indeed. I am Miss Turner.”

“Miss Jones,” Sarah said, bobbing a curtsy with a confidence that didn’t match the lie.

“Miss White,” Alice whispered, barely audible.

James leaned toward William, eyes wide. “They’re all… very pretty.”

“How the hell did we pull this off?” he hissed.

“Luck,” William muttered, though something uneasy churned in his gut. He had expected desperation. He had expected hard-eyed spinsters with no options. He hadn’t expected dignity, and he certainly hadn’t expected the way Mary’s dark gaze seemed to assess him and find him lacking.

“The wagon is this way,” William commanded. “We have a four-hour ride to the ranch. I trust you brought only what you can carry.”

“We brought what we have,” Mary said.

As the men loaded trunks into the back of two buckboards, the sisters shared a fleeting, terrified glance. It lasted less than a second, but it was the kind of glance that carried a thousand words.

We made it.

We are not safe yet.

Do not break.

The ride to Blackwood Ranch was an awkward interrogation disguised as small talk. Dust rose in clouds behind the wagons, settling into hair and eyelashes and the folds of dresses. The wind kept trying to steal hats from heads and secrets from mouths.

In the first wagon, William drove with Mary beside him, reins steady in his hands. Thomas and Alice sat in the back, close enough that Thomas could feel Alice trembling whenever the wagon hit a rut.

“So, Miss Smith,” William said after a while, eyes still on the trail. “Boston is a long way. Why leave?”

Mary had rehearsed this. She had rehearsed it until the lie tasted like something she could swallow without choking.

“The city is crowded,” she said. “Loud. I wanted open space. I wanted to be… useful.”

“You’ll be useful here,” William replied bluntly. “House needs running. Men need feeding.” He hesitated, and then the truth of his own intentions came out hard. “And I need an heir.”

In the back, Alice inhaled sharply, scandalized.

Mary’s spine stiffened. “I am aware of the duties of a wife,” she said, voice turning colder. “But I expect the respect due to a partner, not a servant, and certainly not a broodmare.”

William glanced at her, surprise flickering across his severe face. Most women he’d known would have lowered their eyes. Mary met his gaze like a challenge.

“I treat my horses better than most men treat their wives,” William said, not defensively, but as if stating a fact. “You’ll be safe. That’s what I promised.”

“Safe,” Mary repeated softly. The word tasted bitter. “Safety is a luxury.”

William didn’t answer. He simply drove, jaw tight, as if he recognized that truth too well.

In the second wagon, James tried charm the way he tried everything, like a man gambling with loaded dice.

“So,” he said, tipping his hat toward Elizabeth, “you read books?”

“I read,” Elizabeth corrected, eyes on the horizon.

“I’ve read a book once,” James said, as if that was an achievement. “It was about… a whale.”

“Moby-Dick?” Elizabeth asked without looking at him.

James blinked. “No. Just… a big fish.”

Elizabeth’s mouth twitched, almost a smile, but she didn’t grant him the full satisfaction.

“And what is it you do, Mr. Blackwood,” she asked, “besides follow your brother’s orders?”

James laughed, a sharp bark. “Ouch. You’ve got claws.”

“I have standards,” Elizabeth replied. “They are not the same thing.”

Behind them, Henry and Sarah sat in a quieter peace. Sarah watched the way Henry handled the horses, gentle and steady, like he respected living things. The silence between them felt less like emptiness and more like room to breathe.

“I can shoot,” Sarah said suddenly.

Henry looked at her, startled. “Pardon?”

“I can shoot,” she repeated, chin lifted. “And ride. I don’t want to be stuck in a kitchen all day. I want to help with the herd.”

Henry’s smile was slow, genuine, like sunrise breaking through cloud. “Well, Miss Jones… you might be the first woman in this territory to ask for a saddle instead of a stove. I reckon we can find you a horse.”

Sarah’s eyes softened for half a second, as if she’d forgotten how it felt to be taken seriously.

By the time the ranch came into view, the sun was setting, casting the Montana sky in deep purples and gold. The Blackwood Ranch looked like a fortress: a sprawling two-story log house, massive barns, corrals filled with restless cattle. Strong. Solid.

Mary felt relief and guilt twist together inside her. This place could be a sanctuary. But it could also become a trap.

As the wagons rolled up to the porch, a man waited.

He wore a tin star on his chest.

Sheriff Miller.

William pulled the horses to a stop, frowning. “Sheriff.”

The sheriff’s gaze swept over the four women like he was counting them for a reason. “Will.”

“Trouble?” William asked.

Sheriff Miller spit tobacco into the dust, grim. “Got a telegram from Chicago. Man named Thaddeus Thorne is offering a five-thousand-dollar reward for four sisters. Says they’re thieves. Stole family heirlooms and ran.”

The world narrowed for Mary. Blood drained from Alice’s face. Sarah’s hands clenched. Elizabeth went perfectly still, every muscle turning to calculation.

William’s brow furrowed. “What’s that to us?”

“Just passing the word,” the sheriff said. “Five thousand is a lot. Folks kill for less. Thought you boys should keep an eye out for strangers.”

Mary forced air into her lungs and made her voice steady. “We are just tired travelers, Sheriff. We know nothing of thieves.”

The sheriff tipped his hat. “Ma’am. Welcome to Copper Creek.”

When he rode away, William turned to Mary, eyes narrowed. “Five thousand,” he said. “That’s a king’s ransom.”

Mary nodded, heart hammering like a trapped bird. “Yes,” she whispered. “It certainly is.”

And in her head, she added the part she could never say out loud:

We are worth more to him than we are to ourselves, because to Thorne, women were not people. They were collateral.

The wedding was not a fairy tale. It was a transaction performed in the ranch parlor, witnessed by a justice of the peace who smelled faintly of gin and horse liniment.

Four times the same question, four times the same answer:

“Do you take this woman?”

“I do.”

“Do you take this man?”

“I do.”

Four signatures on a ledger. Four simple gold bands slipped onto trembling fingers. Twenty minutes, and the Davenport sisters vanished on paper.

They ate dinner afterward: roasted pig, cornbread, beans. The conversation limped, awkward and careful, because every person at that table understood what came after the meal. The sun would go down. Bedroom doors would close.

Thomas kept glancing at Alice as if he were afraid she might disappear between bites. “Do you… do you like the food, Mrs. Blackwood?” he asked.

Alice jumped, nearly dropping her fork. “Please call me Alice,” she whispered. “And yes. It is… hearty.”

“I made it,” Henry mumbled, looking at his plate like it held answers.

“It’s delicious,” Sarah said, touching Henry’s forearm lightly.

Henry froze, then slowly relaxed, as if he was learning the difference between touch that threatened and touch that comforted.

That night, the house settled into a heavy, expectant silence.

In the master bedroom, Mary sat on the edge of the quilt-covered bed with her hands folded in her lap. Her posture looked calm. Inside, she was pure tension. A small knife lay hidden in her garter. If William tried to force her, she would use it. She would rather die than go back to being property.

William stood by the window, staring out at darkness. When he finally turned, his gaze landed on her, then on the bed, then on the small cot he had set up in the corner.

“I’m a hard man, Mary,” he said quietly. The use of her true first name startled her, like he’d reached under the lie and touched something real. “I’ve killed men who crossed me. I drive my brothers hard. But I am not a savage.”

Mary’s fingers tightened in her lap.

“You’re scared,” William continued, voice low. “Stiff as a board. I don’t know why you came here. Maybe poverty. Maybe scandal. Maybe running from something.” His eyes held hers. “I don’t care. But I won’t take a wife who looks at me like I’m an executioner.”

He sat down on the cot and began pulling off his boots.

“The bed is yours,” he said. “I’ll sleep here until you’re ready. If that takes a week, fine. If it takes a year, fine.”

Something loosened inside Mary’s chest, painful and unexpected. A tear stung behind her eyes.

“Thank you,” she whispered before she could stop herself.

“Don’t thank me,” he grunted, lying down and turning his back. “Just be up by five. There’s cows to milk.”

Down the hall, James entered his room carrying a bottle of whiskey and two glasses, wearing his signature grin like armor.

“To the happy couple,” he said, pouring.

Elizabeth took the glass, sniffed it, then poured the whiskey into a potted fern by the window.

“I don’t drink spirits, Mr. Blackwood,” she said crisply, “and I don’t appreciate a husband who smells like a saloon.”

James’s smile faltered. “You’re not much fun, are you, Lizzy?”

“My name is Elizabeth,” she corrected. “And I didn’t come here for fun. I came here for stability.” Her gaze flicked toward the desk. “I noticed your ledger was open downstairs.”

James’s eyes narrowed. “You looked at my books?”

“Someone has to,” Elizabeth said. “Your arithmetic is atrocious.”

She crossed her arms. “I will sleep on the left side of the bed. You will sleep on the right. If you touch me without invitation, I will scream loud enough to wake the dead. Good night.”

She blew out the candle.

In darkness, James stood stunned, humiliated, and, to his own horror, intrigued. No woman had ever spoken to him like that. He lay down on his side of the bed and stared at the ceiling, wondering if he had just married his match.

The next morning, ranch life hit the sisters like a physical blow. The work did not end. Water had to be hauled. Wood chopped. Bread kneaded. Dust fought them like a living thing, settling over every cleaned surface as if mocking them.

But the harder work was the secrecy.

In the laundry shed at midmorning, the sound of washboards and bubbling water covered their whispers. It was the only place the sisters could be together without the men watching their faces.

“Thomas is sweet,” Alice whispered, hands raw from lye soap. “He slept on the floor. He read me poetry until I fell asleep.”

“But I almost called Sarah by her name at breakfast,” Alice added, eyes wide. “I bit my tongue so hard it bled.”

“You have to focus,” Mary hissed, scrubbing a shirt violently. “William watches everything. He noticed I hold my teacup the same way Elizabeth does. He asked if we learned etiquette at the same school.”

“What did you say?” Sarah demanded.

Mary’s jaw tightened. “I said all refined women are taught the same.”

Sarah glanced toward the small window, where the ridge north of the ranch rose like a watchful spine. “I checked the perimeter,” she murmured. “If Thorne sends men, they’ll come from that ridge. I’m stashing a rifle in the barn loft.”

Elizabeth adjusted her spectacles, her eyes sharp. “James is hiding something too. The finances are worse than he admitted. He owes money to a gambler in town. A man named Silas Vane.”

Mary’s stomach sank. “Great. We ran from one debt collector and married into another.”

“We have to fix this,” Elizabeth said, voice firm. “If the ranch fails, we have nowhere to hide.”

“I can fix the books,” Elizabeth continued. “But James won’t let me near them.”

“Then steal them,” Mary said, without hesitation.

Sarah blinked. “Mary.”

“We need this ranch,” Mary replied, voice steady. “We are Blackwoods now. We protect this land as if it were our own. Because now it is.”

In that moment, the lie shifted into something heavier. Something like commitment. Something like belonging.

July brought heat that baked the Montana soil into cracked pottery. Tempers flared easily, and the ranch became a living thing, all sweat and dust and sharp-edged survival. But it also became something else: an ecosystem. Chaotic, stubborn, and strangely alive.

Sarah stopped pretending she was meant for domestic life. When a steer broke its leg in a ravine, Henry rode out to put it down, jaw clenched with the pain of doing necessary things. Sarah followed.

When Henry struggled to lift the animal, Sarah dismounted, rolled up her sleeves, and leveraged the steer with a skill that shocked him. She splinted the leg with a branch and strips torn from her petticoat.

“Where did you learn that?” Henry asked, wiping sweat from his brow.

Sarah’s eyes flicked away. “An uncle. He… worked with animals.”

It was a half-truth, built from the shadow of a childhood spent in stables, not parlors.

“You’re handy,” Henry said. It was a rare compliment, and it warmed Sarah more than the sun. “Better than James, anyway.”

From that day on, Sarah rode with Henry. The other brothers grumbled, but William silenced them.

“She pulls her weight,” William said. “That’s more than I can say for Thomas half the time.”

Meanwhile, inside the house, another war brewed.

James came home late one night smelling of smoke and cheap perfume. He found Elizabeth at the kitchen table with the ranch ledger spread open.

“What do you think you’re doing?” James snapped, lunging to grab the book.

Elizabeth slammed her hand down on the page. “Saving you from ruin, you idiot.”

James’s face flushed with anger and humiliation. “It’s none of your business.”

“It is when my roof depends on it,” Elizabeth shot back. She stood, stepping close enough that they were nose to nose. “You are paying twenty percent interest on a loan from Silas Vane. That is robbery. I renegotiated the feed contract with the miller today and saved forty dollars a month. That money goes to Vane. We clear the principal in six months if you stop gambling.”

James stared at her, chest heaving. He had expected a delicate flower he could ignore. Instead, he had married a woman who could see straight through his bravado and into his shame.

“Why?” he asked quietly, the question rough. “Why do you care?”

Elizabeth’s voice softened, but only slightly. “Because I don’t run,” she said. “And I don’t let my family fail.”

James looked at her for a long moment. Then he reached into his pocket, pulled out a deck of cards, and tossed it into the stove. The cards curled and blackened in the flames like a sacrifice.

“You handle the money,” he said hoarsely. “I’ll handle the cows.”

It was a truce. It was also the first time Elizabeth saw something like honesty in his eyes.

Peace, however, was fragile.

The following Tuesday, William took Mary into Copper Creek for supplies. He called it necessity, but Mary felt the test beneath it. He wanted to see how she moved in public, how she spoke, whether her fear betrayed her.

They walked along the boardwalk, William tipping his hat to neighbors, Mary clutching his arm because the touch made her look like a wife, not a fugitive. Eyes followed them. Mary’s skin prickled. Every stranger looked like a hunter.

“You’re shaking,” William murmured as they entered the general store.

“I’m cold,” Mary lied.

It was eighty degrees.

William didn’t press, but his gaze sharpened, watchful.

Mary wandered toward the wall where notices were pinned. Her heart stopped.

Half buried beneath an advertisement for a cattle auction was a wanted poster. Crude sketch, but recognizable enough to make bile rise in her throat.

Four women. The Davenport sisters. Wanted for larceny and fraud.

Reward: $5,000.

Mary’s hand trembled as she ripped the poster down and shoved it into her reticule. She turned just as William looked up from paying for flour.

“What was that?” he asked.

Mary swallowed. “Nothing,” she gasped. “Just… a recipe for apple pie.”

William’s eyes narrowed. He had seen the bold header. He knew. But he said nothing then. He simply ushered her into the wagon and drove out of town in silence that felt like a storm gathering.

That night, the tension at dinner was thick. William brooded. Mary couldn’t meet his eyes. Sarah and Henry ate quietly, shoulders tense. Elizabeth kept glancing toward James as if calculating how quickly they could leave if they had to. Alice looked like a startled rabbit.

Then came a knock at the heavy oak door.

No one visited after dark.

William stood, grabbing the Winchester rifle from above the mantle. “Stay here,” he ordered.

He opened the door.

A man in a sleek black suit stood on the porch, a bowler hat perched on his head like he belonged in a city, not Montana dirt. His shoes were polished. His mustache waxed. His eyes looked like something cold-blooded.

“Good evening,” the stranger said smoothly. “Silas Vane. I believe your brother James knows me.”

James went pale. “Vane… I told you I’d have your payment next week.”

“Oh, I’m not here for the money, Jimmy,” Vane said, stepping inside without invitation. His eyes swept over the table, lingering on the women as if they were items on a shelf. “I received an interesting telegram from an associate in Chicago. A Mr. Thorne.”

Alice let out a small squeak.

Vane smiled like he enjoyed the sound. “Mr. Thorne is looking for some runaway assets. He describes the women as spirited, cultured, and strikingly beautiful. Much like the new brides of the Blackwood Ranch.”

Henry’s hand drifted to the steak knife.

“Get your hand off her chair,” Henry growled when Vane’s fingers rested on the back of Sarah’s seat.

Vane lifted his hands in mock surrender. “Easy, cowboy. Just conversation.”

William cocked the rifle. The sound was deafening in the sudden quiet.

“Get out,” William said.

Vane backed toward the door, smile still in place. “Five thousand dollars is a lot of money, Mr. Blackwood. Enough to pay off your brother’s debts and then some.” His eyes glittered. “I’ll be back. Next time I’ll bring the sheriff.”

He tipped his hat and vanished into the night.

When the door latched, William turned toward the women, eyes blazing.

“Who are you?” he roared. “And don’t you dare lie to me again.”

Mary stood. The room seemed to tilt, but she kept her footing. She looked at her sisters. Sarah was ready to fight. Elizabeth was already calculating survival. Alice was crying openly now, unable to hold it in.

“Our name is Davenport,” Mary said, voice steady. “And we didn’t steal anything. We ran because our father sold us to that monster to pay a debt. If we go back, we are dead.”

She turned her eyes to William. For the first time, she let him see the pleading she’d been swallowing for weeks.

“We lied to you,” she admitted. “I’m sorry. But we are not thieves. We are women who want to live.”

Silence fell, heavy as snow.

The brothers looked at their wives: strangers, liars, fugitives… and, somehow, family.

James looked at Elizabeth and remembered her fingers on the ledger, fixing his ruin without being asked.

Henry looked at Sarah and remembered her hands splinting a calf’s leg, refusing to be fragile.

Thomas looked at Alice and remembered poetry whispered in candlelight and the way she had tried to be brave.

William looked at Mary and saw the terror she had hidden behind spine-straight posture. He saw the strength it took to confess when she could have run.

“They’ll come for you,” William said finally, voice rough. “If Vane knows, Thorne is already on a train.”

“We know,” Mary said. “We’ll leave tonight. We’ll pack and—”

“No,” William cut her off.

He looked at his brothers. “James,” he demanded, “how much do you owe Vane?”

James swallowed. “Two thousand.”

William’s eyes narrowed. “Then Vane has motive to sell them out.”

He turned back to Mary. “You signed the paper. You wear the ring. You are Blackwoods now.”

He moved to the window, staring into the dark where Vane had disappeared, voice turning into iron.

“Nobody takes anything from this ranch,” William said. “Not cattle. Not horses. And sure as hell not our wives.”

He turned back. “Henry, board up the windows. James, check the ammunition. Ladies,” he said, and his gaze pinned each sister, “stop crying. If you’re going to be Blackwoods, you learn to shoot.”

The next three days were steel, oil, and gunpowder. The house stopped being a home and became a fortification. Washing and cooking faded beneath the urgent work of survival.

“If you can’t shoot,” William declared, “you can’t stay.”

In the corral, Mary struggled with the weight of a Winchester rifle. Her shoulder bruised purple from recoil, but she refused to stop. William stood behind her, guiding her hands, his chest close enough that she could feel the heat of him.

“You’re flinching,” he said, stern but not unkind. “You’re anticipating the kick. Don’t fight the gun. Let it become part of your arm.”

“It’s heavy,” Mary gritted out, wiping sweat from her brow. “And I hate it.”

“You don’t have to love it,” William murmured, his breath warm against her ear. “You just have to trust it. And trust me.”

His hands lingered on her waist a second longer than necessary. For the first time, Mary didn’t pull away. She leaned into him, drawing strength from the solidity of his body.

“Breathe out,” William commanded. “Squeeze. Don’t pull.”

Crack.

A bottle on a fence post fifty yards away exploded into shards of amber glass.

Mary lowered the rifle, breathing hard. William’s eyes held something fierce and proud, and it made her knees weak in a way fear never had.

“Good,” he said roughly. “Again.”

On the porch, James set up tin cans for Elizabeth. “It’s simple physics,” he said, trying to sound confident. “Velocity. Trajectory. Impact. You love math, right?”

“I prefer theoretical mathematics,” Elizabeth replied, taking the revolver like it offended her, “not ballistics designed to puncture organs.”

“Think of the can as my debt,” James said with a grin. “And the bullet as your budget cut. Eliminate the debt.”

Elizabeth’s mouth twitched. She raised the gun, calculated distance, and fired. The bullet missed by inches.

“Too much thinking,” James said, stepping close. He wrapped his hand around hers. “Feel it. You want it gone. Make it gone.”

They stood together, gun smoke mixing with the scent of her soap. James looked at her profile, the sharp jaw, the determination, and realized with a jolt that respect had become something deeper, something dangerous.

“I’ve got you,” he whispered.

In the barn, Henry and Sarah trained like equals. Sarah was a natural shot, steady and fierce, but Henry taught her close defense, handing her a hunting knife.

“If they get inside,” Henry said low, “a gun is useless.”

“I’m not afraid of blood,” Sarah replied, gripping the knife. “I’ve slaughtered chickens.”

“This is different,” Henry said, pain flashing in his eyes. “These are men. Bad men.”

Sarah stepped forward, dropped the knife, and took Henry’s face in her hands. The shy giant froze.

“They won’t touch me,” she said fiercely. “Because I have you. You are the strongest man I’ve ever known.”

Henry made a sound like a wounded bear and pulled her into a crushing embrace. When he kissed her, it was clumsy and desperate, tasting of fear and hope, and when they broke apart, Henry looked like he could tear a mountain in half.

“I won’t let them near you,” he swore.

That night, the bedroom doors did not close on strangers.

In the master bedroom, William sat on the edge of the bed, the cot folded away. “Thorne will be here tomorrow,” he said.

“I know,” Mary replied.

William started, “If this goes wrong, I have a horse saddled in North Canyon. You and your sisters can—”

“No,” Mary cut him off, stepping between his knees. “I am done running, William. I am a Blackwood.”

She unbuttoned his shirt with hands that trembled only a little. William’s breath hitched. He cupped her face with hands callused enough to stop thorns, yet touched her with gentleness that felt like worship.

“Mary,” he whispered.

She kissed him. Not tentative. A claim.

Outside, war waited. Inside, for one night, they let themselves believe in something worth fighting for.

The morning sun rose blood red over the peaks. The air was still, birds silent as if the world itself held its breath.

William stood on the porch with black coffee in his hand and his Winchester against the rail. Inside, the women melted lead to cast extra bullets. The smell of metal and fear filled the house.

“Dust,” James called from the roof where he sat with a telescope. “Five miles out. A lot of it.”

William tossed coffee dregs into the dirt. “Get ready.”

An hour later, they arrived.

It wasn’t a posse. It was a small army: twelve riders with repeaters and sidearms flanking a black carriage. Silas Vane rode at the front, smug as a man who thought he had already won.

The carriage door opened and Thaddeus Thorne stepped out.

He looked like a man who had never sweated. Tailored gray suit. Silk cravat. Silver-tipped cane. His gaze swept the rugged ranch house with aristocratic disgust.

“Mr. Blackwood,” Thorne called, voice smooth and confident. “I presume.”

William stepped off the porch and walked twenty paces into the yard, thumbs hooked in his belt. “You’re trespassing, Thorne.”

“I’m retrieving stolen property,” Thorne said, smile cold. “You are harboring four fugitives. The Davenport sisters. Thieves. Liars. And technically my property by way of their father’s debts.”

“I don’t know any Davenports,” William replied evenly. “Only Mrs. Mary Blackwood, Mrs. Elizabeth Blackwood, Mrs. Sarah Blackwood, and Mrs. Alice Blackwood.”

Thorne’s smile vanished. “Marriage does not absolve crime. I have a warrant. And I have twelve men paid very well to enforce it.”

William’s voice turned deadly calm. “I have three brothers and a lot of open land to bury people in.”

Thorne sighed, checking his pocket watch. “How tedious. I offer you a deal. Hand over the women and I’ll leave you five thousand dollars. You can buy new wives. Better ones.”

Inside, Mary’s hands tightened on her rifle. She felt cold rage creep under her skin like ice.

“Go to hell,” William said.

Thorne nodded toward Vane. “Burn it down.”

Chaos erupted.

Gunfire shattered the morning. Bullets chewed dirt around William’s boots as he sprinted back to the porch, firing his revolver.

“Get down!” he roared, diving through the door as wood splintered around the frame.

Inside, the house became a machine of war. William barked orders. James took the east window. Henry covered the back. Thomas went upstairs with Alice.

Mary braced the Winchester on the kitchen sill. A man ran toward the water trough. She remembered William’s voice.

Breathe. Squeeze.

She fired. The man spun and fell.

She didn’t feel sick. She felt resolve, cold and hard.

“Nice shot, Mrs. Blackwood!” James yelled, reloading.

But Thorne’s men fought like professionals. They suppressed the windows while others flanked.

“They’re going for the barn!” Sarah screamed.

“The horses!” Henry shouted, and before anyone could stop him, he bolted out the back door.

“Cover him!” William ordered.

They unleashed a hail of lead. Henry made it to the barn and slammed the heavy doors shut, but Silas Vane had climbed the ridge above, grinning like a devil.

He lit a rag stuffed into a bottle of kerosene.

The bottle shattered against the dry roof.

Whoosh.

Flames ate the hay loft in seconds.

“The barn’s on fire!” Alice shrieked from upstairs.

Inside the barn, horses screamed. Smoke thickened. Henry’s chest burned. He couldn’t open the main doors. The exit was pinned.

“Henry!” Sarah’s voice cut through the chaos.

She didn’t think. She didn’t ask permission. She ran.

A bullet grazed her arm, ripping fabric, but she reached the side door and kicked it in. Heat slapped her face like a hand.

“Get them out!” Sarah coughed, grabbing a rope.

“It’s suicide!” Henry shouted.

“It’s death to stay!” she snapped back. “Mount up. We break through.”

They burst from the burning barn on horseback, flames behind them like wings. Sarah fired one-handed from the saddle. Two men went down. They reached the porch just as the barn roof collapsed in a storm of sparks.

Henry tumbled inside, soot-blackened, and caught Sarah’s face between his hands.

“Are you hit?” he demanded.

“Just a scratch,” she panted. “We saved most of the horses.”

“You are a maniac,” Henry said, and kissed her forehead hard. “A beautiful maniac.”

But then James shouted, voice cutting through smoke and screams.

“They’re bringing up the carriage!”

Two men rolled out something heavy and iron.

Thomas squinted. “Is that… a Gatling gun?”

William’s face went pale. “Where the hell did he get a Gatling gun?”

“Money buys everything,” Elizabeth said grimly.

The crank began to turn.

William screamed, “DOWN! FLAT!”

The sound was like canvas ripping. Hundreds of rounds tore through the log walls. Plates shattered. Furniture splintered. Sawdust filled the air like choking snow. They couldn’t lift their heads.

“We can’t hold this!” James shouted.

“We need to flank it,” William said, mind racing. Then Elizabeth grabbed his arm, eyes bright with calculation and courage.

“The cellar,” she said. “The root cellar has a ventilation tunnel. It comes out near the well. It’s small. A man can’t fit.”

Alice’s trembling voice rose. “I can.”

Thomas turned on her, horror and love tangled. “No.”

“I can fit,” Alice insisted, her voice gaining strength. “I can crawl through. If I reach the well, I can shoot the man cranking the gun.”

William’s jaw clenched. “It’s too dangerous.”

“We are going to die in here!” Alice cried, tears streaking her dirty cheeks. “Let me do this.”

The Gatling gun paused to reload, and the sudden silence was almost worse.

Mary stepped toward Alice and took her sister’s face in her hands, just like in that Boston room. “Go,” Mary whispered. “Go now.”

Thomas hugged Alice hard, shaking. “Be brave, my love.”

Alice slipped into the cellar, into darkness that smelled of damp earth and rot. She crawled on elbows and knees, dirt scraping her skin raw. Above, the vibration of gunfire shook dust into her eyes. She wanted to stop. She wanted to be nineteen again, crying into a handkerchief about poetry.

But Thomas’s voice echoed in her mind.

Be brave, my love.

She reached the end of the tunnel and pushed up a wooden grate hidden in weeds near the old stone well. Fresh air hit her face, stinging with gunpowder.

The Gatling gun was twenty feet away. The gunner laughed as he turned the crank. Thorne stood nearby, watching destruction with glee.

Alice pulled herself out and stood. Small, torn dress, dirt-smeared face. She raised a pearl-handled derringer with two shots.

“Hey!” she screamed.

The gunner turned, startled. Thorne’s eyes widened.

“You,” Thorne sneered. “The little poet.”

“Leave my family alone,” Alice said, voice trembling but loud.

The gunner reached for his sidearm.

Alice fired.

The shot hit his shoulder, not his heart, but shock made him stumble backward. He tripped over the ammunition box, fell hard, and knocked the Gatling gun off its tripod. The barrel slammed into dirt and jammed.

Silence fell like a miracle.

Inside the shredded house, William heard the gun stop.

“NOW!” he roared.

The front door exploded open. William, James, Henry, and Thomas surged out, screaming like men who had run out of fear. Behind them, Mary, Elizabeth, and Sarah fired from the windows.

Thorne’s hired guns saw their heavy weapon down. Courage, bought with money, evaporated faster than sweat in the Montana sun.

“Retreat!” someone yelled.

James sprinted toward the ridge, where Silas Vane tried to reload. Vane fumbled, eyes wide, but James tackled him and they rolled in the dust, fists flying. Vane was scrappy. James was fighting for more than pride now.

James landed a solid hook. Vane went limp.

James stood over him, panting, blood on his lip. “Account closed,” he rasped.

Near the well, Thorne grabbed Alice, twisting her arm behind her back and pressing a knife to her throat.

“Stay back!” Thorne shrieked as William approached. “I’ll cut her!”

Thomas lifted his rifle, hands shaking, no clear shot.

“You’ve lost, Thorne,” William said, voice deadly calm. “Your men are running. Vane is down. Let her go.”

“I’m not leaving empty-handed,” Thorne spat. “She’s worth five thousand dollars.”

Mary stepped into the yard, rifle steady, eyes locked on Alice’s. Alice nodded, barely perceptible.

Alice stomped hard on Thorne’s foot and slammed her head back into his nose. Thorne howled, grip loosening.

Alice dropped.

Mary fired.

The bullet struck dirt between Thorne’s feet, spraying gravel into his legs, forcing him back.

Before he could recover, William was on him.

William didn’t use a gun. He used his fists. One punch doubled Thorne. Another sent him sprawling in mud.

Thorne tried to crawl toward his cane.

A boot slammed on his hand.

Elizabeth stood over him holding James’s revolver, spectacles slightly crooked, eyes like ice.

“The interest on your cruelty has compounded, Mr. Thorne,” she said. “And today is payday.”

Thorne looked up at the circle of brothers and sisters. Not fear. Not pleading. Only iron.

“Sheriff Miller is on his way,” William said. “He can decide if hanging is in order.”

Thorne’s shoulders sagged, defeated, as if the West itself had finally told him no.

Three months later, the first snow blanketed the ranch in quiet white. The house had been repaired. New logs. Thicker glass. The barn rose again, frame strong against the gray sky.

Inside, fire roared in the hearth. The smell of roasting turkey and sage filled the air.

It was Thanksgiving.

The long table was set for eight, and there was no silence now. There was laughter, the kind that came from people who had stared death in the face and decided to live loudly anyway.

James told the battle story for the tenth time, making Vane bigger with every retelling. Elizabeth rolled her eyes but let her hand rest on James’s knee, her touch steady. She was pregnant, just beginning to show, and the ranch ledger on the desk was closed, the numbers finally in the black.

Henry and Sarah argued playfully about horses. Sarah had started a breeding program, and her mustangs were already becoming famous in the county. Henry looked at her like reverence had become his favorite language.

Thomas sat by the fire with Alice leaning on his shoulder. He read a poem he had written himself, not borrowed from a book. It was about a girl who crawled through darkness to save the light. Alice listened, fingers tracing the fading scars on her hands, and smiled like she had earned every piece of peace she held.

William stood at the head of the table carving the bird. Mary stood beside him, hair looser now, her city severity softened by prairie wind and hard-won belonging. She looked like a woman who belonged to land and family and her own name again.

William raised his glass.

“To the advertisement,” he said, eyes twinkling. “Best damn investment I ever made.”

“To the sisters,” Mary corrected, lifting her own glass. “Who ordered husbands and got a militia.”

“To the Blackwoods!” James shouted.

“To family,” Alice whispered.

They drank.

Outside, wind howled, but it didn’t matter. The walls were thick. The fire was warm. The table was full.

They had survived the lie, the debt, and the bullets. They had learned that love wasn’t always soft. Sometimes it was a rifle in steady hands. Sometimes it was a ledger balanced against ruin. Sometimes it was crawling through damp earth because you refused to let the people you loved be taken.

And that was the legend of the Blackwood brothers and the Davenport sisters, rewritten not as a secret to hide, but as a story to pass down.

A dynasty forged in fire, sealed with rings, and held together by the simple, stubborn truth that no one gets to call a human being “property” on Blackwood land.

THE END

News

No Widow Survived One Week in His Bed… Until the Obese One Stayed & Said “I’m Not Afraid of You”

Candlelight trembled on the carved walnut door and made the brass handle gleam like a warning. In the narrow gap…

How This Pregnant Widow Turned a Broken Wagon Train Into a Perfect Winter Shelter

The wind did not blow across the prairie so much as it bit its way through it, teeth-first, as if…

“Give Me The FAT One!” Mountain Man SAID After Being Offered 10 Mail-Order Brides

They lined the women up like a row of candles in daylight, as if the town of Silverpine could snuff…

The Obese Daughter Sent as a Joke — But the Rancher Chose Her Forever

The wind on the high plains didn’t just blow. It judged. It came slicing over the Wyoming grassland with a…

He Saw Her Counting Pennies For A Loaf Of Bread, The Cowboy Filled Her Cupboards Without A Word

The general store always smelled like two worlds arguing politely. Sawdust and sugar. Leather tack and peppermint sticks. Kerosene and…

He Posted a Notice for a Ranch Cook — A Single Widow with Children Answered and Changed Everything..

The notice hung crooked on the frostbitten post outside the Mason Creek Trading Hall, like it had been nailed there…

End of content

No more pages to load