HE DIED BEING JOHN WAYNE AND THE STUDIO CALLED IT “GOODWILL”

The desert in mid-October looked like it always did in Monument Valley, all red stone and hard sunlight, like the world had been carved from rust and left to cool. The crew had been up since before dawn, chasing the sweet spot when shadows made the buttes look taller than they were, and everyone moved with that strange mix of boredom and vigilance that only exists on a film set. A horse doesn’t know about budgets or call sheets, and gravity doesn’t care if the camera is rolling. Pete Keller did, though. Pete knew every angle, every hoofbeat, every tiny lie a stunt could tolerate before it turned into truth.

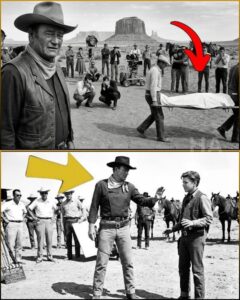

They were filming a run that looked simple on paper: speed, dust, a controlled fall, a man who gets up like pain is just part of the costume. Pete had done stunts for fifteen years and coordinated them long enough to smell trouble before it arrived. He had the kind of hands that never stopped measuring space, the kind of eyes that saw the end of a motion before the beginning finished. He checked the saddle strap, spoke low to the horse like they were partners in a quiet crime, and nodded at the wranglers with a confidence that wasn’t bravado so much as responsibility. Somewhere behind the camera, John Wayne stood ready to be John Wayne, and somewhere in the shadow of that legend, Pete prepared to be him more honestly than the audience would ever know.

The fall went wrong in the smallest way, the way disasters love to do it, as if they’re embarrassed to arrive loudly. The horse’s footing slipped, just a fraction, and the animal’s weight shifted into an angle Pete hadn’t planned for. He hit the ground at the wrong slant, and the snap that followed was not dramatic, not cinematic, not scored with music. It was just sound, dry and final, carrying across the open desert like a message nobody wanted delivered. A few people shouted his name, but their voices sounded far away, swallowed by space and shock. The director froze with a hand raised as if he could halt time, and then lowered it because time doesn’t take direction. John Wayne stood about twenty feet away, face set like stone, and his hands betrayed him, shaking at his sides.

Medics ran in, kneeling in the dirt that would later be brushed off boots and forgotten by the hotel carpets. They checked for pulse, for breath, for the small stubborn miracle that sometimes visits in emergencies, but the body answered with nothing. Someone whispered, “He’s gone,” as if saying it softly could make the truth less sharp. The sheriff came, asked questions, took statements, and ruled it accidental because the law prefers clean labels for messy losses. The cameras stopped, the horses were led away, and fifty people stood in a rough circle around the place where a man had become a headline no one would print. By evening, the crew had returned to a motel in Mexican Hat, Utah, forty miles from the set, and the hallways felt too quiet, as if laughter would be inappropriate noise.

Pete Keller was thirty-eight, married, father of three kids, ages six, eight, and eleven, and he’d never had a serious injury until the day he died. Those details moved through the crew like a cold draft, because numbers make grief easier to carry and harder to ignore. People said things like, “He was good,” and “He always had it under control,” because those were the safest words available. Some avoided the bar completely, and some sat there staring at their drinks as if the amber could explain the physics of injustice. Kirk Douglas, the co-star, walked past Wayne in the lobby and paused, the way men do when they want to offer comfort but hate the feeling of helplessness. “This business,” Douglas said quietly, not finishing the sentence because finishing it would mean admitting what they all knew: the business was built on risk, and risk was usually carried by people whose names never reached the marquee.

Linda Keller didn’t see the desert. She saw her kitchen, her kids’ jackets tossed over a chair, the ordinary clutter of a life that assumed tomorrow would arrive with Pete in it. The call came six hours earlier, and the words kept repeating in her head as if her mind believed repetition might reverse them. A neighbor took the kids into the other room, turned on the television too loud, and tried to distract them with cartoons that suddenly seemed cruelly cheerful. Linda sat at her table with red eyes and empty hands, waiting for something that could not be waited through. When the knock came, she expected family, a friend, a human being with a heartbeat of sympathy. Instead, she opened the door to a junior studio lawyer in a suit and tie, carrying a clipboard like a shield.

He was polite in the way professionals are polite when they want to finish a task without touching it emotionally. He offered condolences as if reading from a script, then sat at her table like he’d sat at dozens of tables before. Papers slid out, smooth and official, and he spoke about Pete as a “valued member of our team,” which sounded like something you’d say about equipment you were replacing. “Universal Pictures would like to offer a settlement,” he said, tapping the number with a pen. “Five thousand dollars. Sign here, and we’ll have a check to you within two weeks.” Linda stared at the figure like it was a typo that would correct itself if she blinked hard enough. When she didn’t move, he added the line that made her hands start trembling: “It’s a generous offer, Mrs. Keller. Pete knew the risks. This isn’t a liability situation. The studio is offering this out of goodwill.”

Goodwill. The word landed wrong, like a boot on a broken rib. Linda thought about the mortgage, the grocery bill, the way Pete’s oldest had been talking about college even though college was years away, as if dreaming early made it more possible. She thought about the nights she’d patched him up and kissed bruises like they were temporary storms, believing that careful love could bargain with danger. She wanted to ask the lawyer if he had children, and if he would trade their future for five thousand dollars and a deadline. Instead, she watched his jaw tighten when she didn’t reach for the pen. “Take it or leave it,” he said, the sympathy draining from his voice as the schedule reasserted itself. “This offer expires in forty-eight hours.” He stood, nodded once, and left her with papers that treated a man’s life like a minor expense in a three-million-dollar picture.

That night, John Wayne didn’t sleep. He sat in his motel room in Mexican Hat, the air smelling faintly of dust and cigarette smoke, staring at the ceiling like it might project answers. He’d been in the business for forty years and had seen men get hurt, but death was different, and it clung to the mind the way desert heat clings to skin even after sundown. Wayne kept hearing the snap, kept seeing the way Pete fell, kept thinking about the line no one said out loud: Pete died so Wayne could keep being a legend on camera. Two years earlier Wayne had faced lung cancer, and the thought of fragility irritated him the way it irritates most powerful men, because fragility is the one opponent you can’t punch. Somewhere in his mind, his seven children appeared, not as a proud list but as a question: what if the world measured him the way it had measured Pete? At dawn, when the phone rang, Wayne picked up with the heavy patience of a man who already knew he wouldn’t like what he’d hear.

The unit production manager spoke in a tone that tried to be casual, as if insulting a widow was just another line item. “Studio sent the standard offer,” he said. “Five grand. Accidental death, no liability.” Wayne listened long enough to hear the justification too, the part that always comes packaged with cruelty: “Legally, we don’t have to offer anything.” Silence stretched on Wayne’s end of the line, thick as mud. He didn’t argue about policy, because policy was a costume people wore when they wanted to avoid looking in a mirror. He just hung up, sat on the edge of the bed, and let the thought settle like a stone in his gut: a man died being me, and the company that profits from my face thinks his family is worth less than a new car.

Wayne called his business manager next, not for advice, but for capability. “How much cash can I access today?” he asked, voice flat, the way it gets when a decision has already been made. The manager hesitated, probably expecting talk of investments or studio deals, not a sudden act of personal justice. Wayne didn’t explain at first, because explaining would invite negotiation, and negotiation was exactly what he was tired of. When he did speak, it came out simple: “A man’s widow is being cornered into signing her dignity away.” The manager named numbers, accounts, logistics, and Wayne heard them like a man hearing a bridge being built under his feet. By mid-morning, he had an envelope in his jacket and a destination in his mind that no studio executive could reroute.

Linda Keller was still at her kitchen table forty-eight hours later, the settlement papers staring at her like an ultimatum. She had read them so many times the words had started to blur into a single message: your grief has an expiration date. The lawyer had called twice, each time reminding her of the deadline in the voice you’d use to remind someone their library book was due. She needed money, and the need was practical and sharp, the kind that doesn’t care about pride when the fridge is empty. And yet the idea of signing felt like agreeing that Pete’s life, his sacrifices, his fatherhood, could be reduced to a number chosen for convenience. When the knock came again, she expected the lawyer returning to collect her surrender.

Instead, she opened the door and saw John Wayne, filling the doorway like an icon that had stepped off a billboard and into her real life. For a second she wondered if grief had started inventing hallucinations, because nothing else made sense. Wayne removed his hat, and the gesture was small but deliberate, a sign that he had come as a man, not just a star. “Mrs. Keller,” he said, voice quieter than the screen ever allowed it to be. Linda’s throat tightened so hard she could barely nod. She let him in because not letting him in felt like refusing reality, and reality was already doing plenty of refusing on her behalf.

He sat at the same kitchen table where the lawyer had sat, but he didn’t pull out papers. He looked at her like he was trying to hold the weight of what had happened without dropping it on her again. “I’m sorry about Pete,” he said, and it didn’t sound like a line, it sounded like a man finally letting himself feel the cost. Linda stared at her hands, afraid that if she looked up she would break apart. Wayne’s jaw tightened when he mentioned the offer. “Five thousand dollars,” he said, as if tasting something bitter. “That’s not a settlement. That’s an insult.” Tears filled Linda’s eyes because someone had finally said the word she’d been swallowing. “I need the money,” she whispered. “But signing feels like saying he didn’t matter.” Wayne reached into his jacket, placed an envelope on the table, and slid it toward her with steady fingers. “This is fifty thousand,” he said. “From me. Not the studio. For you and the kids.”

Linda’s breath caught, panic and disbelief colliding in her chest. “I can’t accept that,” she said, because decent people hate feeling indebted, especially when they’re already drowning. Wayne shook his head once, firm but not unkind. “Yes, you can,” he replied. “Pete died making my movie. He died because I’m too old to do what he did for me.” The sentence hung between them, raw with an honesty Hollywood usually edited out. Linda tried to protest again, but Wayne’s eyes held hers, and she saw something there that wasn’t celebrity at all; it was responsibility, ugly and unglamorous, the kind that shows up when the cameras are off. “He died being me,” Wayne said. “The least I can do is make sure his family doesn’t get treated like an afterthought.”

Then Wayne did the part that made the studio’s spine go cold. He took out a business card, wrote a number on it, and placed it beside the envelope like a weapon wrapped in ink. “That’s the studio head’s direct line,” he told her. “I’m calling him today. Universal is going to set up a monthly stipend for you, five hundred dollars a month for life, and they’re going to create college funds for your kids, full tuition.” Linda’s tears finally spilled because the promise sounded impossible in a world that had just shown her how cheaply it could price a human life. “Why would they do that?” she asked, voice shaking. Wayne’s mouth hardened. “Because if they don’t, I walk off every picture I owe them, and I’ll make sure every newspaper in America knows exactly why.”

The phone call that afternoon wasn’t loud, and that was part of its power. Wayne didn’t need to shout; he needed to be unmovable. He laid out the facts like a judge reading a sentence: Pete Keller died making a Universal picture, left behind a widow and three children, and the studio tried to buy silence with five thousand dollars and a ticking clock. The studio head tried the usual defenses, words like “insurance” and “standard practice” and “no liability,” each one designed to drain humanity from the conversation. Wayne cut through them with a simple refusal to hide behind procedure. “I don’t care about standard practice,” he said. “I care about right and wrong.” When the executive asked what he wanted, Wayne gave the number and the terms, not as a request but as a correction. The silence that followed was the sound of a man calculating profits against principles, and realizing profits would lose if principles threatened the bottom line. “Fine,” the studio head said at last. “We’ll do it.” Wayne demanded it in writing, legal, contract, unbreakable, because he knew how quickly goodwill evaporates when the spotlight moves on.

Six weeks later, Linda received the first stipend check, five hundred dollars like clockwork, a small monthly proof that someone had forced the system to remember her name. Her mortgage was seven hundred, and the stipend covered most of it, while Wayne’s fifty thousand covered the rest and the groceries and the shoes kids outgrow overnight. Linda took a part-time job at a grocery store not because she had to prove anything, but because work gave her structure when grief tried to dissolve her days. She never remarried, not out of bitterness, but because Pete had been her person and she didn’t want a replacement for a love that still felt present. The kids grew up with a father-shaped absence and a mother who learned how to be two parents without turning hard. College became real instead of mythical, first for the oldest, then the middle, then the youngest, each acceptance letter a quiet defiance of the day a lawyer tried to put an expiration date on their future. Universal paid because John Wayne made them, but the kids didn’t grow up worshipping Wayne as a hero so much as understanding the rarer lesson underneath: power can crush, or it can protect, and the difference is a choice.

Linda collected that stipend for thirty-seven years, until she died in 2003 at seventy-one, and the math itself became a kind of moral evidence. Two hundred twenty-two thousand dollars in monthly checks, plus Wayne’s fifty thousand, plus three full college educations, each dollar a rebuttal to the original offer that tried to turn a man into a bargain. Nothing brought Pete back, and nobody pretended it did. But dignity is its own form of survival, and Linda’s life became proof that grief doesn’t have to be accompanied by financial ruin if someone, somewhere, refuses to let the machine roll on unattended. In 2005, Linda’s daughter Sarah wrote a letter to the John Wayne estate, her words steady with the kind of gratitude that comes from seeing your mother saved when she couldn’t save herself. Sarah was a high school history teacher in San Diego by then, teaching students how systems work and how people either submit to them or challenge them. She wrote about the day Wayne sat at their kitchen table, about the envelope and the phone call and the way her mother’s shoulders finally lowered, just a little, because somebody had fought for her when she had no fight left.

The letter ended up displayed in a museum, beside a photo of Pete Keller and the settlement papers Universal had wanted Linda to sign, and beside a copy of Wayne’s personal check. Tourists walked past it every day, reading with the casual curiosity of people who like stories about old Hollywood, yet some of them stopped longer than they expected. Maybe they imagined the snap in the desert, the silence afterward, the widow staring at a number that tried to define her life. Maybe they recognized the modern version of that lawyer, the one who hides cruelty inside “policy,” and felt a quiet anger rise in their own throats. And maybe, for a moment, they understood the most uncomfortable truth in the whole story: stuntmen die being other people, and unless somebody makes a fuss, the world will let them disappear like dust. John Wayne couldn’t undo death, but he could make death expensive enough that the studio regretted treating a family like collateral damage. That is how you measure a man, Sarah wrote in spirit if not in exact words: not by the legend he plays, but by the burden he chooses to carry when no one is watching.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load