The heat in the Lowcountry didn’t simply sit on the land, it pressed down like a judgment.

On the veranda of Whitcomb Plantation, the boards creaked under the boots of Colonel Everett Whitcomb, a man who owned more acres than most people could imagine and more cruelty than he ever bothered to hide. Beyond the white columns, the cotton rows stretched toward a bleached horizon, shimmering, as if the earth itself tried to blink away what it kept witnessing.

He had his hand wrapped around his daughter’s forearm, squeezing hard enough to leave pale fingerprints in her skin.

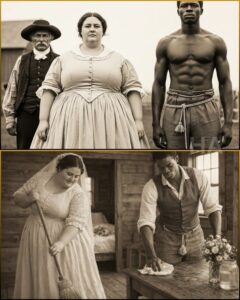

Lillian Whitcomb stood beside him, twenty-two and broad-shouldered, her body full in a way the ladies in Charleston whispered about behind fans and lace gloves. Her brown hair had been pinned too tightly, her cheeks flushed from the heat and from the humiliation of being displayed like a problem the household couldn’t solve. She didn’t plead. She didn’t protest. She couldn’t.

Her silence had been a story told so often that everyone believed it was the only version: the colonel’s daughter, struck dumb as a child by a fever, doomed to live behind curtains and locked doors like a shameful heirloom.

But Lillian’s eyes were alive. Not vacant. Not broken. Alive, sharp with questions she had never been allowed to ask out loud.

Down the steps, near the yard where the wagons waited, the strongest man on the place stood with his hands at his sides, as still as a carved post.

His name was Isaiah.

Isaiah Carter, they called him, though he’d once had a name that tasted of riverwater and drums and something older than this country’s lies. His shoulders were wide as a barn door. His arms were roped with muscle built from years of lifting sacks that would make three men curse. Even the overseer, a lean man with a snake’s grin, looked at Isaiah like he was a tool that could turn dangerous if handled wrong.

The colonel’s voice cut through the yard like a whip crack.

“Take her,” Whitcomb said, loud enough for every field hand and house servant and hired man to hear. “She’s yours now. Do what you like. But get her away from my house. I’m finished carrying my own embarrassment.”

A few heads lifted. A few eyes flickered. Nobody spoke. Silence was what Whitcomb sold in bulk, same as cotton.

Lillian’s fingers curled slightly, the only sign of tremor. She didn’t move away from her father’s grip because she knew what happened when she did.

Isaiah didn’t move right away either.

He only looked at her, a long, steady look that didn’t crawl over her body the way other men’s eyes sometimes did. His gaze went straight to her face, to the corners of her mouth where words had been punished into hiding, to the thin pulse in her throat that still kept time.

Then, quietly, he stepped forward.

“Sir,” Isaiah said, voice deep and even, “if you’re giving her to me, you’re giving her under my roof. My rules.”

Whitcomb’s mouth twitched, almost amused. “Rules,” he echoed, as if it were the funniest thing he’d heard all week. “You don’t have rules, Carter. You have chores.”

Isaiah’s jaw tightened, but he didn’t argue. Not here. Not in this yard.

He turned to Lillian and held out his hand.

For a second, she stared at it like it was a foreign object, something from a different life. Then she placed her palm in his. His skin was callused and warm, the kind of hand that had been forced to build everything and allowed to own nothing.

Isaiah guided her down the steps and away from the bright white house that had always swallowed her like a secret.

As they walked, the overseer muttered something vulgar under his breath. A few men snickered. A woman near the wash line crossed herself as if watching a funeral procession.

And Whitcomb, satisfied, lit a cigar and leaned back in his chair, already forgetting that he had just thrown a human life into the dirt like a cracked horseshoe.

That was the moment the plantation began to split, not with fire or gunshot, but with something far more dangerous.

Truth.

The cabin they gave Isaiah sat at the edge of the quarters, close enough that the overseer could keep an eye on him, far enough that the big house didn’t have to hear his footsteps at night.

It was a two-room shack with a sagging roof and a door that didn’t latch right unless you shoved it with your shoulder. Somebody had tossed a straw mattress in the corner and called it “married accommodations” with a laugh sharp enough to draw blood.

Isaiah didn’t laugh.

He led Lillian inside and closed the door behind them, then pushed the latch into place with a careful firmness, like he was sealing a promise.

She stood in the center of the room, breathing fast. The air smelled of pine resin and old smoke and something damp under the floorboards. Her eyes darted to the bed, then to Isaiah’s hands, then back to the door as if she expected her father to burst in and announce she’d been traded again.

Isaiah took two steps backward and sat down on the floor, leaning his shoulders against the wall.

“I’m not touching you,” he said.

Lillian blinked.

He tilted his head, studying her expression as if he could read the words she’d swallowed for years. “I know what they think,” he continued. “They think you’re punishment. They think you’re bait. They think I’m supposed to break you so your father can sleep easy.”

Lillian’s fingers rose, hesitant, then dropped again. Her mouth opened slightly. No sound came.

Isaiah’s gaze softened, just a notch. “You don’t have to speak tonight,” he said. “Just breathe.”

The space between them filled with the quiet crackle of a distant insect chorus, and the far-off groan of a wagon wheel turning somewhere in the dark.

After a long minute, Isaiah spoke again, lower this time, as if the walls had ears.

“You’re not silent because you can’t make sound,” he said. “You’re silent because someone taught you it was safer.”

That landed in the room like a stone.

Lillian’s throat bobbed. Her eyes widened, not with fear now, but with a fierce, startled kind of recognition. Her hands rose again, faster this time, forming questions in the air: How? Why?

Isaiah didn’t answer immediately. His fingers rubbed once over a faint scar near his wrist, the old habit of someone who carried memories like a hidden blade.

“I saw things,” he said at last. “In the big house. In places they didn’t think I’d ever look.”

Lillian’s breath hitched.

Isaiah’s voice stayed steady, but something tightened behind his eyes. “There’s a crawlspace above the pantry,” he said. “You can only get to it if you climb the beams in the storage room. Last year, I was sent up there to fix a leak. I found papers stuffed inside a tin box, wrapped in cloth like they were trying to keep them from the light.”

He paused, then added, “Your name was on them.”

Lillian swayed slightly, as if the room had tilted. She grabbed the edge of the table for balance.

Isaiah watched her carefully. “You want to know what they said?” he asked.

Her chin lifted, sharp, defiant. She nodded once.

Isaiah exhaled through his nose, slow. “They weren’t land deeds,” he said. “They weren’t cotton accounts. They were… records. A bill of sale. Not for you as a lady. For you as property.”

Lillian’s hands flew to her mouth.

Isaiah’s voice hardened like cooling iron. “And the name listed under ‘mother’ wasn’t Whitcomb’s wife.”

He let that sit, because it was the kind of truth that needed room to expand.

Lillian’s eyes glistened. Not with helplessness.

With fury.

Isaiah leaned forward slightly. “Your father didn’t ‘lose’ your voice to a fever,” he said. “He locked it away. Same as he locked you away. Because if you ever spoke too loud, someone might hear what your blood already tells the world.”

Lillian’s fingers trembled, then pressed against her throat as if trying to feel the shape of a word.

Isaiah’s expression softened again, but his resolve didn’t. “I’m going to help you get it back,” he said. “And when you do… we’ll make sure the whole plantation hears.”

Outside, thunder rumbled far off over the marsh, the kind of sound that promised a storm was walking toward them on heavy feet.

And Lillian, for the first time in years, did something that looked like hope.

Morning came with a sun so bright it looked cruel.

The big house gleamed. The fields filled with bodies moving in practiced rhythm. The overseer barked orders. Life wore its usual mask.

But under the mask, something had changed.

Lillian walked beside Isaiah when he went to the tool shed, carrying a small basket as if she belonged there. People stared. Some stared with pity. Others with disbelief. A few stared with a kind of hungry curiosity, the way people stare at a crack spreading in a wall they’ve always pretended was solid.

The overseer, Mr. Harlan Briggs, sauntered up with his whip looped loose in his hand, smiling like a man who thought the world owed him entertainment.

“Well now,” Briggs drawled, eyes flicking over Lillian like she was livestock. “Colonel’s finally rid of his little ghost. What’s it like, Carter? Bedding a mute whale?”

Isaiah didn’t flinch. He only looked at Briggs the way a storm cloud looks at a field.

“She’s under my roof,” Isaiah said. “Watch your mouth.”

Briggs laughed, too loud. “Listen to that,” he said to no one in particular. “The ox thinks he’s a man.”

Lillian’s cheeks reddened. Her hands clenched tight around the basket handle.

Isaiah stepped half a pace forward, and the laughter died around the edges. Even Briggs seemed to remember, for a thin moment, that Isaiah’s strength wasn’t just rumor.

“Go back to your job,” Isaiah said.

Briggs narrowed his eyes, then spat into the dirt. “You’ll learn your place,” he muttered, and strutted off.

When he was gone, Lillian turned her face up toward Isaiah, eyes burning. Her hands moved quick: I want him to suffer.

Isaiah’s gaze didn’t waver. “He will,” he said quietly. “But not the way he expects.”

That afternoon, Isaiah led Lillian to the creek behind the cypress line, where the water ran dark and slow, carrying the sky on its back.

He knelt, cupped water in his palms, and lifted it to her face. The touch was gentle, careful, like he was washing away years of dust that weren’t just physical.

Lillian closed her eyes, letting the coolness sink into her skin. When she opened them, her expression was different. Less like someone waiting for permission to exist.

More like someone preparing to claim her own name.

Isaiah sat back on his heels. “Say one sound,” he told her.

Lillian swallowed hard. Her lips parted. A rasp came out, faint as a leaf scraping stone.

Isaiah nodded, as if she’d just moved a mountain. “Again,” he said.

Her throat worked. The rasp became a whisper of air shaped into something almost like a word.

Isaiah’s voice stayed calm, but pride flickered in his eyes. “They trained your silence,” he said. “We’ll train your voice.”

Lillian’s hands moved: What’s my voice for?

Isaiah looked at the creek, then at her. “For truth,” he said. “And for freedom.”

The word freedom hung between them, bright and dangerous.

They both knew it wasn’t a simple thing you could pick up and carry home like a loaf of bread. It had teeth. It had consequences. It had men with guns who would call it “rebellion” and spill blood to keep it from spreading.

But Isaiah spoke it anyway, as if saying it was the first crack in the dam.

That night, after the quarters settled into uneasy sleep, Isaiah waited until the big house dimmed its lanterns.

Then he moved.

He slipped through the pantry door, climbed the storage beams like a shadow, and reached into the crawlspace where the tin box had been hidden.

He brought it back to the cabin wrapped in cloth.

Lillian watched with her whole body held tight, like she was bracing for the past to bite her.

Isaiah opened it slowly.

Inside were papers, yellowed and stiff, written in careful ink. A thin gold locket lay in the corner, tarnished but still shaped like a heart. There were letters too, folded so many times the creases looked like scars.

Isaiah spread the papers on the table.

Lillian leaned close, reading what she could. She had been taught letters as a lady, but only the kind that made her a decorative daughter, not the kind that could save her life.

Isaiah pointed to a line.

There, beneath her name, was another.

Mother: Rosetta.

And beside it, in smaller writing, a note that made Isaiah’s jaw tighten:

“Mulatto child. Purchased quietly. Keep indoors.”

Lillian’s hands flew to her mouth again. Her eyes flashed, then filled, then hardened.

Isaiah’s finger moved to another paper.

A baptism record, copied from a church ledger.

Lillian Rosetta Whitcomb, it read, and then, like a knife turned in flesh:

Father: E. Whitcomb. Witness: I. Carter.

Lillian looked up so fast Isaiah almost felt the wind of it.

Her hands moved in a frantic question: You?

Isaiah’s face was grim. “I was a boy,” he said. “I didn’t know what it meant then. They called me in from the yard because they needed a witness who couldn’t testify against them.”

Lillian stared at him like she was seeing his face for the first time.

Isaiah’s voice dropped. “The name ‘Carter’ wasn’t mine. They gave it to me after they bought me from a trader up in Richmond. But my mother… my mother was Rosetta too.”

The room went still, as if even the air stopped moving.

Lillian’s breath stuttered. Her hands slowed, shaping something softer, more terrified: Brother?

Isaiah didn’t answer with words right away. He only nodded once, heavy and certain.

Lillian’s knees buckled, and she caught herself on the edge of the table, shaking. A sound escaped her, broken and raw, not quite a sob, not quite a laugh, something in between that carried years of locked doors.

Isaiah stood, stepping toward her, not to claim her, not to frighten her, but to steady her.

“Your father thought giving you to me would bury rumors,” Isaiah said. “He thought if the strongest man on the plantation ‘took’ you, it would turn your life into something nobody respectable would ever speak about. He wanted the story to end before it began.”

Lillian’s lips moved soundlessly around the shape of a word.

Isaiah watched her with a focus that felt like prayer. “Say it,” he urged.

Her throat worked. Her voice scraped out, small but clear enough to be real.

“Why?”

Isaiah’s eyes closed for a heartbeat. When he opened them, they looked older than the plantation.

“Because he’s afraid,” Isaiah said. “Afraid of what you are. Afraid of what you prove.”

Lillian’s voice trembled, but she pushed it forward like a stubborn door. “What… do I prove?”

Isaiah leaned closer, speaking like every syllable mattered.

“You prove he built his empire on theft,” Isaiah said. “Not just of land. Of people. Of blood.”

He tapped the letters on the table. “And if those papers get into the right hands, Whitcomb won’t just lose his reputation. He’ll lose everything.”

Lillian’s breathing steadied.

Something changed in her eyes.

The fear didn’t vanish. It transformed.

Into purpose.

It would have been easy, in a different kind of story, for the plantation to explode overnight.

But real cruelty doesn’t fall with one dramatic gust. It clings. It bargains. It hires lawyers. It buys judges. It smiles at church and murders behind barns.

So Isaiah and Lillian moved carefully.

They didn’t shout. Not yet.

They planted.

Lillian started walking through the quarters in the evenings, bringing scraps of cloth for bandages, a bit of soap, a few biscuits she’d stolen from the big house pantry with the quiet skill of someone who’d been trapped there long enough to learn its blind spots. People watched her at first as if she were a trick. Then they started to watch her as if she were a signal.

She didn’t speak much. Not because she couldn’t anymore, but because every word was still a muscle recovering from years of being held down. When she did speak, it came out rough, like a voice digging itself out of dirt.

“I… see you,” she told an older woman with scarred hands, and the woman stared at her like she’d just heard thunder in a clear sky.

Isaiah, meanwhile, made copies of the papers at night with charcoal and careful strokes. He had learned letters in secret from a preacher who believed God didn’t hand out intelligence based on skin. He copied each line until his fingers cramped.

Then came the most dangerous step.

A trip to the church.

The nearest one was a small clapboard building outside the plantation boundary, where white parishioners sat on polished benches and Black congregants, when allowed inside at all, were expected to stand in the back like shadows.

But the church kept records.

And records, Isaiah knew, could become weapons sharper than knives.

They went on a night when the moon was fat and bright, because darkness hid bodies but moonlight guided feet.

Isaiah carried the tin box under his shirt. Lillian walked beside him, her posture straight, her breath steady. The woods around them whispered with insects and rustling leaves, and every snap of a twig sounded like a gun cocking.

When they reached the church, the door was locked.

Isaiah knocked once.

A moment later, the door opened a crack, and the face of Reverend Amos Kline appeared, lantern light painting his features in wary gold.

“What do you want?” Kline whispered sharply when he saw Isaiah. “You know you shouldn’t be here after dark.”

Lillian stepped forward into the lantern glow.

Reverend Kline froze.

“You,” he breathed, as if a memory had just climbed out of a grave.

Lillian lifted her chin and forced her voice out, low but present. “I… need… the book.”

Kline’s eyes flicked from her face to Isaiah’s. “Colonel Whitcomb will—”

“He already did,” Isaiah cut in. “Now either you open that ledger, Reverend, or you spend the rest of your life preaching about mercy while you ignore a sin sitting on your own shelf.”

Kline flinched, but the flinch wasn’t fear. It was shame.

He stepped back and opened the door wider.

Inside, the church smelled of old wood and candle wax and hymns that had been sung by people praying for deliverance while men like Whitcomb counted money.

Kline led them to the back room, where the record books sat in a chest like sleeping beasts.

His hands trembled as he lifted the lid.

“What year?” he asked.

Isaiah named it.

Kline flipped pages, the paper whispering under his fingers. He stopped, eyes narrowing.

Then his face went pale.

He turned the book so Lillian could see.

There it was.

Her name.

Her mother’s name.

And next to it, in a notation so small it had likely been meant to be missed:

“Born of Rosetta, enslaved. Condition of child disputed.”

Kline swallowed.

Isaiah’s voice was quiet, but it hit like a hammer. “What does ‘disputed’ mean, Reverend?”

Kline’s eyes lifted. He looked at Lillian, and something softened there.

“It means… someone argued she wasn’t property,” Kline said. “It means someone said she was… entitled to freedom.”

Lillian’s breath caught. Her voice came out in a thin, shaking thread. “Who?”

Kline hesitated, then pointed to a faint signature in the margin.

A name Isaiah hadn’t expected.

Rosetta.

Lillian stared at it like the ink might move.

Isaiah felt his chest tighten. His mother, Rosetta, had signed a document in a world that tried to erase her literacy, her personhood, her very right to leave a mark.

Kline’s voice dropped. “Colonel Whitcomb’s wife demanded it be sealed,” he whispered. “She said the child would ‘ruin the family.’”

Isaiah’s jaw clenched.

Lillian’s hands curled into fists.

Then footsteps sounded outside the church, heavy and quick.

All three of them stiffened.

Isaiah shoved the ledger back into the chest. Kline snapped the lid shut.

The doorknob rattled.

A voice hissed through the crack: “Reverend! Open up!”

Mr. Briggs.

Isaiah’s heartbeat didn’t race. It sharpened.

Lillian’s eyes widened, but she didn’t shrink. She grabbed Isaiah’s sleeve, not to stop him, but to stay anchored.

Kline whispered, “Go. Now. Through the side window.”

Isaiah didn’t argue. He pulled Lillian toward the small window, lifted it, and helped her out into the night.

They hit the ground running, the moonlight silvering the leaves around them.

Behind them, the church door banged open.

Briggs’s voice roared, “Carter! You think you’re clever?”

Isaiah didn’t look back until the trees swallowed the church and its angry lantern light.

When he did look back, he saw Briggs standing in the doorway like a stain that refused to wash out.

And Isaiah knew.

The quiet part of their fight was over.

Colonel Whitcomb didn’t confront them right away.

That was his first mistake.

He tried to smother the problem the way he smothered everything else: with money, intimidation, and the assumption that nobody beneath him could keep standing if he pressed hard enough.

The next day, he called a meeting in the big house parlor with the local magistrate, a lawyer from Charleston with slick hair and colder eyes, and Reverend Kline, whose hands shook so badly he could barely hold his hat.

Whitcomb paced beneath a portrait of his “ancestors,” men whose faces had the smug calm of people who’d never feared consequences.

“This is slander,” Whitcomb snapped. “A plot cooked up by an overgrown field brute and a defective girl who can’t even string a sentence together.”

Lillian stood outside beneath the live oak, listening through the open window, Isaiah beside her.

Her chest rose and fell, steadying. She didn’t hide anymore.

Isaiah’s voice stayed low. “He’s trying to decide whether to crush us fast or quiet,” he murmured.

Lillian’s lips moved around hard syllables. “Let… him… try.”

Inside, the lawyer’s voice oiled the air. “If there are documents,” he said, “we seize them. If there are witnesses, we frighten them. The law bends toward property, Colonel. It always has.”

Reverend Kline’s voice cracked. “She spoke,” he whispered. “Lillian spoke to me.”

Whitcomb stopped pacing.

The room went silent.

“What did you say?” Whitcomb asked, dangerously calm.

Kline’s throat bobbed. “She… asked for the ledger.”

Whitcomb’s eyes turned into knives. “That girl hasn’t spoken a word in fifteen years.”

Outside, Lillian’s hand rose to her throat.

Isaiah leaned slightly closer, as if his presence could shield her from the sound of her father’s rage even through walls.

Whitcomb’s voice grew thin with panic, though he tried to dress it up as fury. “If she’s speaking now,” he said, “it’s because that brute is forcing her. Corrupting her. You know what these people do. They—”

“Colonel,” the magistrate said carefully, “if the church record indicates an irregularity… there may have to be a hearing.”

Whitcomb’s head snapped toward him. “In my county?” he barked. “In my state?”

The magistrate’s face tightened. “In Charleston, then,” he said. “Before a circuit judge.”

Whitcomb’s nostrils flared. He looked like a man watching the ground under his feet begin to shift.

Outside, Isaiah exhaled slowly.

Lillian’s gaze didn’t waver.

She turned her head toward Isaiah and spoke, voice rough but real. “We… go… Charleston.”

Isaiah’s eyes met hers. “We go,” he agreed. “But we don’t go alone.”

That night, Isaiah moved through the quarters, quiet as smoke.

He spoke to people who had survived Whitcomb’s punishments, who had lost children to sales, who had buried friends in unmarked ground.

He didn’t promise miracles.

He promised a chance.

“We need testimony,” he told them. “We need names. We need the truth they’ve been forced to swallow.”

Some people shook their heads, terror carved into their faces.

But others… others lifted their chins the way Lillian had begun to lift hers.

An older man named Josiah stepped forward, voice hoarse. “I remember Rosetta,” he said. “I remember her screaming the night they took the baby.”

A woman with braided hair, hands raw from washing, whispered, “I saw the colonel’s wife burn letters in the kitchen hearth.”

A young man with a fresh scar on his cheek said, “Briggs beat my brother near to death because he asked for Sunday off. I’ll speak.”

Isaiah listened, gathering their stories like kindling.

And Lillian, sitting in the cabin doorway, practiced her voice in the dark.

Not pretty.

Not polished.

But hers.

The day the hearing began, Charleston looked like a city wearing perfume to hide rot.

Carriages rolled past pastel houses. Men in clean coats talked about morality while their wealth leaned on the backs of people they refused to see. The courthouse stood tall and smug, a temple built to worship paper.

Whitcomb arrived dressed in his finest, face pale but stiff with pride.

He brought his lawyer. He brought Briggs. He brought two armed men who stood behind him like punctuation marks.

Isaiah arrived in plain clothes, wrists bare, shoulders squared.

He brought Lillian.

And behind them came a small line of Black men and women, walking like they had decided to stop being shadows.

People stared. Murmurs ran through the street.

“That’s Whitcomb’s girl,” someone whispered. “I heard she can’t talk.”

Lillian heard them. Her jaw set.

Inside the courtroom, the judge sat high, eyes bored at first, as if he expected another tedious property dispute.

Whitcomb’s lawyer began with a smooth voice and ugly assumptions. “Your Honor,” he said, “this is a fabrication born of insolence. A brute—”

Isaiah stepped forward. “My name is Isaiah Carter,” he said clearly. “And I’m here to present documents.”

The judge frowned. “Do you have counsel?”

Isaiah’s gaze flicked briefly to Reverend Kline, who stood near the back, then back to the judge. “No, sir,” Isaiah said. “But I have evidence.”

The judge looked irritated, then curious. “Proceed,” he said, as if granting permission to an inconvenience.

Isaiah laid the copied papers on the clerk’s desk.

The courtroom quieted as the judge read.

Whitcomb’s face tightened.

The lawyer tried to object, but the judge held up a hand.

Then the judge’s eyes narrowed at the baptism record, at the note about “disputed condition,” at Rosetta’s signature.

He looked up slowly.

“Colonel Whitcomb,” the judge said, voice changed now, sharper, “did you purchase this child?”

Whitcomb’s mouth opened, closed.

“She is my daughter,” he snapped. “Legitimate.”

The judge’s gaze slid to Lillian.

“Miss Whitcomb,” he said. “Can you speak for yourself?”

Whitcomb’s lawyer smirked like a man confident in old cruelty.

Lillian’s hands trembled at her sides.

Isaiah didn’t touch her, didn’t lead her, didn’t push.

He only looked at her with steady belief, like a hand extended without grabbing.

Lillian stepped forward.

Her voice came out rough, scraped from years of disuse, but it carried.

“My name,” she said slowly, each word a stone placed down with intention, “is Lillian Rosetta Whitcomb.”

A hiss of shock moved through the room.

Whitcomb’s smirk collapsed.

Lillian kept going, stronger now. “I was… not… born dumb,” she said. “I was… made… quiet.”

Whitcomb’s lawyer sprang up. “Objection! This is theatrics.”

The judge slammed his gavel. “Sit down,” he snapped, and the lawyer sat, startled by the force in the judge’s voice.

Lillian swallowed. Her eyes locked on her father.

“You… took… my mother,” she said, voice trembling with rage and grief braided together. “You… took… me. You hid… papers. You hid… blood.”

Whitcomb’s face went waxy.

Isaiah stepped forward. “We have witnesses,” he said.

One by one, people stood.

Josiah spoke about Rosetta, about the night the baby disappeared.

The braided-haired woman spoke about letters burned in the hearth.

The young man spoke about Briggs’s cruelty, not as rumor, but as fact, with scars as punctuation.

Briggs sneered until the judge’s gaze pinned him.

Then Reverend Kline stood, voice shaking but louder than it had ever been in his pulpit. “The ledger is real,” he said. “And the note indicates she may be entitled to freedom.”

The courtroom felt like it had forgotten how to breathe.

Whitcomb’s lawyer tried to salvage it. “Even if her mother was enslaved, the child—”

The judge held up the record. “The record indicates dispute,” he said, eyes cold now. “And I will not ignore a signature from the mother herself.”

He looked at Whitcomb like a man seeing him clearly for the first time.

“Colonel,” the judge said, “you have built your standing on the assumption that no one would ever challenge you.”

Whitcomb’s lips curled. “This is an outrage,” he hissed. “This is—”

“This is court,” the judge cut in. “And you are not above it.”

Whitcomb’s hands shook.

For a moment, Isaiah thought Whitcomb might reach for a weapon, might choose violence as his last language.

But Whitcomb’s strength had always been borrowed, built from other people’s fear.

And now the fear was leaving the room.

The judge’s ruling did not end slavery that day. It did not rewrite the whole country’s sin in one sweep of a pen.

But it did something that cracked a specific empire.

He ordered a formal investigation into Whitcomb’s property claims and household records.

He ordered Lillian’s legal status reviewed as a contested case with credible evidence of wrongful confinement.

And he ordered Briggs detained for assault pending testimony.

Briggs shouted. Whitcomb lunged. The bailiff caught Briggs by the arm, and the sound of chains in a courthouse was a different kind of music than the chains in the fields.

Outside, in the courthouse steps sun, Whitcomb turned on Lillian, face twisted with something that looked like hatred and terror mixed together.

“You ungrateful,” he spat. “After everything—”

Lillian’s voice, though still rough, came out steady.

“After everything,” she echoed, “I am still standing.”

Whitcomb looked at Isaiah then, eyes full of poison. “You think you’ve won,” he hissed.

Isaiah’s expression didn’t change. “No,” he said. “I think you’ve started losing.”

The months that followed were not soft.

There were threats. There were whispers. There were men who rode past the quarters at night, letting gunshots pop into the air as reminders.

But something had shifted, and shift is what terrifies men like Whitcomb most.

Lillian stayed in Charleston for part of the proceedings, housed quietly by a Black seamstress community who treated her like a person rather than a rumor. Her body, which had been used as an insult her whole life, became something else: a proof of survival. She learned to speak more each day, words coming easier as if they’d been waiting behind a locked door for the key.

Isaiah returned to the plantation with the other witnesses, because leaving the people behind would have been a different kind of betrayal.

Whitcomb tried to sell parcels of land to cover legal costs.

Creditors circled.

His “friends” in polite society began to step away, pretending they’d never drunk his whiskey or laughed at his jokes.

And in the quarters, people began to talk differently, not loud enough to invite death, but loud enough to invite hope.

When the final ruling came down, it was not a fairy-tale ending wrapped in ribbon.

It was harder.

It was real.

Lillian’s confinement was declared unlawful. Her status was recognized as wrongfully controlled, her personhood affirmed in writing that Whitcomb could not burn without consequence.

Briggs was convicted of assault.

Whitcomb’s property titles were found riddled with fraud and “irregular acquisitions.” Not all the land was seized, but enough was challenged that his empire became a leaking ship.

And the court ordered compensation and legal protections for several families Whitcomb had unlawfully separated, a small, insufficient justice, but justice that left paper trails, the kind that could be used again.

On the day Isaiah returned to Charleston to hear the final decision, he found Lillian waiting outside the courthouse, hair pinned back simply, shoulders squared, eyes clearer than he had ever seen them.

She smiled, and it wasn’t sharp this time.

It was human.

“You… did… not… break me,” she said softly.

Isaiah shook his head. “You broke your own chains,” he told her. “I just helped you find the lock.”

She reached into her pocket and pulled out the tarnished locket from the tin box. She opened it. Inside was a faded scrap of hair and a tiny folded paper with a single word written in careful script.

Rosetta.

Lillian’s fingers trembled as she held it, not with fear, but with grief finally allowed to breathe.

“I wish,” she said, voice thick, “she could… see.”

Isaiah’s gaze lowered, then lifted again. “She does,” he said quietly. “Not from heaven. From the way her name is finally being spoken out loud.”

Lillian looked at him for a long moment, then asked the question that had haunted the edge of everything.

“What… are we… now?” she said.

Isaiah understood the knot beneath it: blood, betrayal, love in its many forms, the confusion of a world that had tried to twist them into something ugly for entertainment.

He answered carefully, like laying a blanket over a wound.

“We’re family,” he said. “Not the kind your father tried to fake. The kind that chooses to protect.”

Lillian’s shoulders loosened, as if her body had been holding a breath for twenty-two years.

They walked away from the courthouse together, not as a master and property, not as a scandal, not as a grotesque joke for men like Briggs.

As two people who had survived the same monster.

As siblings in truth.

Back at Whitcomb Plantation, the big house still stood for a while, but it didn’t gleam the same. Paint peeled. Windows stayed shuttered. Whitcomb’s cigar smoke no longer ruled the air.

Years later, Lillian sat on a porch that used to belong to her father, now repurposed into a small office where contracts were signed with fairer terms. The fields had changed too. The work was still hard, because the South didn’t shed its skin quickly. But the word forever no longer belonged to Whitcomb.

Isaiah stood beside her, older now, shoulders still wide, eyes still deep.

A breeze moved through the live oaks, stirring Spanish moss like slow gray curtains.

Lillian spoke, her voice no longer a scraped whisper, but a steady sound shaped by will.

“I used to think,” she said, “silence was my only safe place.”

Isaiah looked at her. “And now?”

Lillian smiled, small and sincere. “Now I think silence is only safe for the people who benefit from it.”

Isaiah’s mouth curved. “That’s the truest thing you’ve ever said.”

She leaned back in her chair and watched the horizon, the land bright under the sun, the future not perfect, not clean, but finally open.

And for the first time in her life, Lillian Whitcomb didn’t feel like a secret.

She felt like a beginning.

THE END

News

OUTTAKES FROM A WINTER RING

(An extra story that explains the hidden twist behind Tomas Crowe, the “seven cents,” and why Evelyn Harrow watched Benita…

FARMER WHO BOUGHT A GIANT SLAVE FOR SEVEN CENTS… AND TRAINED HER IN SECRET

They laughed before the auctioneer even finished clearing his throat. The February air in Natchez, Mississippi, sat heavy on the…

SHE TRADED ONE NIGHT FOR A LIFE… AND HER CEO’S GUILT OPENED A WAR

Sienna Alvarez had learned that hospitals don’t really sleep. They dim their lights and lower their voices, but the place…

The mistress had three twins and ordered the slave to k!ll the one with the most different skin color – but fate had other plans.

The night Magnolia Ridge Plantation learned it was being tested, March rain fell like a stern sermon over the Mississippi…

THE PLANTER “GAVE” HIS HIDDEN DAUGHTER TO AN ENSLAVED MAN… AND NO ONE IMAGINED WHAT HE WOULD DO WITH HER

St. Jerome Plantation stretched across the Louisiana lowlands like a kingdom that didn’t need a crown to feel sovereign. In…

THE BANQUET OF ELEVEN PLANTERS: THE MYSTERIOUS NIGHT AT OAK HOLLOW, LOUISIANA

No one who crossed the threshold of Oak Hollow on the night of December 14, 1873, believed they were walking…

End of content

No more pages to load