1

Our house on Hawthorne Street looked like the kind of place real families lived.

A little porch with a swing Dad never sat on anymore. A maple tree out front that turned the yard into a red-and-gold storm every October. A white picket fence we never painted again after Lily died.

Inside, though, it was a museum.

Lily’s photo was everywhere. Lily at the river in a yellow swimsuit, her hair wet and shiny, smiling like she’d discovered a new planet. Lily holding a stuffed bunny with its ear chewed off. Lily on the couch with her feet tucked under her, watching cartoons, head tilted like she was listening to the TV’s heartbeat.

The photos didn’t just exist. They watched.

And the longer I lived there, the more I felt like I was moving through a house that belonged to someone else, wearing someone else’s clothes, breathing someone else’s air.

The first time Mom made me put on Lily’s dress, I thought it was a mistake.

I was four then. Lily had been three. We were close enough in age that when you squinted, you could pretend we were twins. People already did. “They look like little peas in a pod,” old ladies at the grocery store would say, pinching our cheeks like they were testing fruit.

Then the river happened.

Mom always called it the river like it was a person, like it had a name you weren’t supposed to say out loud. The Cuyahoga wasn’t even that wild where we were. It was shallow near the bank, with smooth rocks and little pockets of reeds. Dad took us there sometimes with a picnic, and Mom would sit on a blanket with sunscreen and a book, watching like she was counting our breaths.

That day, I don’t remember the first moment of panic.

I remember the water being colder than it should’ve been. I remember Lily slipping, her small hand shooting out, my fingers catching hers for half a second before the current yanked her away like a prank. I remember her face, startled, not scared yet, like she was surprised the world could move without asking permission.

I remember trying to hold on.

And I remember letting go.

Later, people told me I was rescued first because I was closer to the bank, because a man waded in and grabbed me, because I was still kicking. They told me I was lucky.

Mom didn’t call it luck.

When the paramedics declared Lily gone, Mom held her little body and made a sound that didn’t belong to a human throat. Dad tried to pull her away and she slapped him so hard his cheek went red. Then she turned her face toward me, my wet hair plastered to my forehead, and she looked at me like I’d stolen something.

“Why did you come back?” she whispered.

That night, after the funeral home took Lily, after neighbors brought casseroles we didn’t eat, after Dad sat at the kitchen table staring at nothing, Mom walked into my room.

She had Lily’s favorite dress in her hands.

“Put this on,” she said.

I stared at it, confused. “That’s Lily’s.”

Mom’s eyes were swollen. Her mouth was a straight, brutal line.

“She needs it,” she said.

“She’s… gone,” I said, because I was four and I still believed saying a thing might make it real enough to handle.

Mom bent down until her face was inches from mine. I could smell toothpaste and grief.

“She’s not gone,” she said. “Not if you help me. Put it on.”

I did.

That was the beginning.

The way some kids learn multiplication tables, I learned how to disappear into someone else’s outline.

2

By the time I turned seven, Mom had rules for me.

Rule one: I was not Noah in public. I was “Lily.”

Rule two: my hair had to stay long.

Rule three: if I “embarrassed” her, there would be consequences.

She never said “I’ll hurt you.” She didn’t need to. Her hands spoke in their own language. A sharp jab to my forehead. A pinch so hard it left crescent moon bruises on my arm. A slap across the back of my head that made my ears ring like small bells.

Dad saw it. That was the part that made everything worse.

He saw it and did the thing he always did, the thing grown men do when they’re afraid of the truth: he went quiet.

Dad wasn’t a monster. That’s what I would’ve told you if you asked me then. He made grilled cheese the way I liked it, with the crust cut off. He kept a toolbox in the garage and fixed my broken robot toy three times even when it kept snapping the same plastic hinge. He tucked a blanket around my shoulders on the couch when I fell asleep watching cartoons, as if warmth could fix what love was failing to.

But whenever Mom’s grief turned sharp and swung through the room like a bat, Dad stepped back and let it happen.

He told himself he was keeping peace.

He was just renting silence, and I was the payment.

School was its own kind of battlefield.

Kids notice things. They notice the way you walk. They notice the way your voice drops lower than the other “girls” by second grade. They notice the way your knees show under your dress when you run, and the way you flinch when someone says your name.

On my first day of second grade at Roosevelt Elementary, Mom walked me to the classroom door, her fingers digging into my wrist like a clamp.

“Remember,” she whispered, her breath hot in my ear. “You are Lily. If you tell anyone otherwise, I’ll take you back to that river and leave you there.”

I nodded so hard my neck hurt.

Inside, the classroom smelled like pencil shavings and hand sanitizer. Ms. Carter smiled and pointed me to a desk. Kids stared, then went back to their chatter.

At recess, it started.

A boy named Brent, who always had a scab on his elbow and an opinion about everything, squinted at me.

“You look weird,” he said.

“I’m not weird,” I said, because I didn’t know any better than to defend myself with the truth.

“You sound like a boy,” he announced, loud enough that a few heads turned.

My stomach dropped. I felt it, the same way you feel a roller coaster crest the hill, the moment before gravity decides what happens next.

“I’m Lily,” I said quickly.

Brent leaned closer, eyes bright with curiosity and cruelty, like he’d found a worm and wanted to see how it moved when you poked it.

“Liar,” he said. “You’re not Lily. Lily’s dead.”

The world tilted.

I didn’t know how he knew. Small towns know things. Grief leaks through walls.

I ran to the bathroom and locked myself in a stall, sitting on the closed toilet lid, knees pressed to my chest, trying to breathe quietly enough that no one would hear me being afraid.

When I got home, Mom saw the dust on my dress, the scrape on my knee, and her face tightened.

“What did you do?” she demanded.

“Nothing,” I said, automatically.

She stepped closer. “Did you talk?”

“No,” I whispered.

“Did you act like him?” she hissed.

I didn’t even know how to answer that. I didn’t know where “me” ended and “him” started, because to Mom, “him” was always the enemy.

I stood still while she yanked my hair, checking if the ponytail was neat enough to pass for Lily’s.

Dad walked in from the garage, wiping grease from his hands. He took one look at my face and his eyes softened.

“What happened, buddy?” he asked, using the word buddy like it was a little rebellion.

Mom snapped her head toward him. “Don’t call him that.”

Dad’s shoulders fell a fraction. “Melissa,” he said, careful. “He’s just a kid.”

Mom’s laugh was sharp and broken. “He’s the kid who came back.”

Dad didn’t argue. He didn’t pick me up. He didn’t say, That’s my son.

He just went to the kitchen and started washing dishes that were already clean.

That was how our days went. Mom’s grief ran the house. Dad tiptoed around it. And I learned to make myself smaller, not because I wanted to, but because the house only had room for one child.

The one who was gone.

3

When Mom got pregnant again, the air in the house changed.

It wasn’t lighter. It was tighter, like the walls were holding their breath.

Mom started humming again, little tunes she used to sing when Lily was a toddler. She organized baby clothes, folding them with a tenderness that made my throat ache. She pinned a list of girl names to the fridge and circled them in pink marker.

Every time she said “she,” her voice went soft.

Every time she looked at me, it went hard.

One evening in late September, I came out of my room because the pain in my stomach from the “candy” was already blooming, even before I swallowed the last bitter trace. I wanted water. I wanted to see Mom’s face, just once, without it twisting into disgust.

Dad noticed me first, standing by the kitchen counter cracking eggs into a bowl. He frowned.

“Noah,” he said, then corrected himself as if remembering the rules. “Lily… why aren’t you doing homework?”

I shrugged. The floral dress clung to my skin. It always did, like it was trying to remind me it didn’t belong.

Dad’s eyes flicked over the dress and then away, like he’d seen something that hurt to look at.

Mom turned from the living room, hand on her belly, smile still on her face until she saw me. The smile froze, like someone had slapped a glass window and left a crack.

“Who told you to come out?” she snapped.

I opened my mouth, but the words got stuck. My stomach churned. Pain rolled through me in a hot wave, and I grabbed the doorframe for balance.

Mom’s gaze dropped to my hair. “You cut it again,” she said, voice rising. “Are you trying to ruin her? I told you to grow it long. Lily’s hair was beautiful.”

“I didn’t cut it,” I said, voice thin. “It just… fell out when I brushed it.”

Mom strode over and jabbed her finger into my forehead so hard it made my eyes water.

“All you do is cause trouble,” she said. “Listen to me. When your sister gets here, if you even look at her wrong, I swear I’ll make you regret it.”

Dad took a step forward, instinctive, like his body remembered he was supposed to protect something.

Mom’s hand shot out and caught his wrist. “Don’t touch him,” she warned. “He’ll fake sick to get attention. That’s all he knows how to do. He steals attention. He stole her life.”

Dad’s jaw tightened. For a moment, I thought he might finally say something real.

But the moment passed. Dad swallowed it, the way you swallow something sharp and pretend it didn’t cut you.

I nodded, like a good substitute. Like a well-trained shadow.

Then I turned and walked back to my room.

Every step felt like knives. My fingers went numb. My vision blurred at the edges, like the world was shutting its blinds.

Behind me, Dad’s voice floated down the hall, soft and pleading.

“Mel, he looks pale.”

Mom’s response was immediate, dismissive. “He always looks pale. He likes the drama.”

In my room, I collapsed onto the bed. The convulsions came like waves, my body moving without permission.

A few minutes later, the door creaked open.

Dad stepped in carrying a cup of warm water, the kind of cup he used when I was sick as a toddler. He set it on the nightstand, hesitated, and then sat on the edge of the bed like Mom used to, except his eyes weren’t hollow. They were tired.

“Your mom’s… going through a lot,” he said quietly. “The pregnancy, everything. Try not to take it personally.”

I wanted to laugh. I wanted to scream. Instead, I made a sound that was barely more than a breath.

Dad pulled the blanket up over me, careful, like he was tucking in a fragile object.

“Get some sleep,” he said. “You’ll feel better tomorrow.”

He left. He closed the door behind him.

The house went silent except for the ticking wall clock in the hallway, counting seconds like they were pennies.

Under my pillow, I pulled out Lily’s cloth bunny. Its fur was worn smooth, one ear flopped permanently, and I’d been cleaning it every day because Mom said it belonged to Lily and had to be kept “perfect.”

When kids at school tried to steal it from my backpack, I fought back and got a bruise on my cheek for it.

I hugged the bunny tight and let my eyes close.

Mom, I thought, Lily’s coming back.

You won’t have to hate me anymore.

That’s good.

That’s really good.

4

When I woke, the pain was gone.

At first, I thought it meant I’d survived. That the poison wasn’t strong enough. That my body had betrayed me again by refusing to disappear.

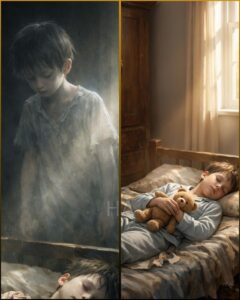

Then I saw my hands.

Light passed through them.

I sat up, but I didn’t feel the sheets, didn’t feel the mattress. My body felt like air wearing the idea of a shape. I looked down and saw my own small frame lying on the bed, floral dress wrinkled, lips tinted an unnatural purple, a dried smear at the corner of my mouth.

My fingers on the bed were clenched around Lily’s bunny like it was a lifeline.

I stared, waiting for horror to hit me, waiting for some big feeling. But what I felt was… quiet.

Like a room after someone turns off the TV.

The door opened. Mom walked in.

She didn’t look at the bed.

She went straight to the desk where Lily’s framed photo sat, picked it up, and wiped the glass with the corner of her shirt like there might be dust she could erase along with the past.

“Lily,” she murmured softly, voice sweet as syrup. “Mommy ordered you a new crib. Do you want pink or blue? Pink, right? My girl always liked pink.”

She turned to leave and kicked the bedframe by accident.

Only then did her eyes flick toward the bed, annoyed.

“Still sleeping?” she snapped. “It’s late. Get up and make breakfast. You think the baby eats itself?”

I floated closer, wanting to speak, to say, I’m right here, I’m not sleeping, I’m gone.

But she walked out, humming a lullaby like the hallway was a cradle.

In the kitchen, Dad was already cooking. I drifted to the doorway and watched him pour batter onto a pan, shaping pancakes into hearts with the back of a spoon. He used to make dinosaur pancakes for me when I was little, lumpy green things that looked nothing like dinosaurs but made me laugh anyway.

After Lily died, everything became hearts.

“Lily loved hearts,” Dad would say, like repeating it could bring her back.

Mom carried the plate to the table with reverence, setting it down like an offering.

“Go wake him up,” she told Dad, impatient. “We need to leave soon. We have to buy the crib today.”

Dad wiped his hands on a towel and walked toward my room.

I followed him, moving easily, weightless.

He stood by the bed and lifted his hand, then let it fall again. Finally, he touched the blanket gently.

“Noah,” he whispered, using my real name without thinking. His voice shook. “Hey, champ. We’re going to pick up a crib. You want to come with us?”

My body didn’t move.

Dad’s fingers trembled. He pressed them to my shoulder, light at first, then a little harder.

“Noah?” he tried again.

Mom’s voice shot down the hallway. “Stop babying him, Dan. He’s pretending.”

She stormed into the room, irritation already loaded like a weapon. Then she saw Dad’s face.

He wasn’t moving.

He was staring at the bed like the bed had opened into a cliff.

“He’s… cold,” Dad whispered, voice cracking.

Mom stepped forward, frown deepening. “What are you doing? He’s trying to ruin this day. He always does. He doesn’t want Lily’s crib in this house.”

Dad didn’t answer.

Mom yanked the blanket down, like she expected me to sit up and smirk.

Instead, she saw my face.

For a beat, the room held its breath.

Mom’s mouth opened and closed, like she couldn’t find the right lie.

“No,” she said finally, voice thin. “No. He’s pretending.”

Dad’s eyes filled, his face folding in on itself. “He’s our child too,” he said, and it sounded like the first time he’d ever said it out loud.

Mom’s scream came out raw. “No! My only child is Lily! He’s the reason she’s dead. He stole her life!”

She grabbed Lily’s framed photo off the desk and hurled it at the floor. The glass shattered. Dad flinched as if it hit him.

He knelt automatically, picking up shards with shaking hands. A piece cut his palm. Blood dotted the carpet.

The phone rang in the living room.

Mom answered without looking at the bed, her voice turning instantly polite.

“Hello, Roosevelt Elementary,” she cooed. “Yes, this is Noah’s mother.”

I heard Ms. Carter’s voice through the receiver, faint but urgent, asking why I hadn’t been in school.

Mom’s tone turned icy. “He’s skipping on purpose,” she said. “He does it to get attention. Don’t waste your time. He’ll deal with the consequences.”

She hung up.

Then she looked back at my body and finally, for the first time, her eyes showed something that wasn’t anger.

It was fear.

Dad pulled his phone out, fingers clumsy. “I’m calling 911,” he said.

Mom lunged and grabbed his wrist. “Don’t,” she hissed. “Don’t call anyone. If people find out… they’ll say we did this. The baby isn’t here yet. We can’t have… a stain.”

Dad’s head snapped up. His voice rose, loud and sudden in a house that had learned to whisper. “He’s seven years old,” he shouted. “He’s our son. Look at him!”

For the first time in three years, Dad shoved Mom away.

He dialed.

When he gave the address, his voice broke so badly he had to repeat it.

Mom sank to the floor, staring at my face like it was an accusation carved in stone. Then she started to cry. Not the angry crying she did when she lost control, but the kind of sobbing that sounded like a person drowning in her own throat.

“I didn’t mean to,” she whispered. “I just… I just wanted her back.”

I floated in front of her, wanting to touch her cheek, wanting to be a kid who could still be held.

My hand passed straight through her face.

5

The paramedics came fast. Their shoes squeaked on the hardwood. Their voices were calm, trained, gentle in a way that felt almost cruel because it was the gentleness I’d needed in my own home.

One of them checked my pulse and then looked at Dad, something heavy settling in his eyes.

“I’m sorry,” he said quietly.

Mom made a sound like she’d been punched. “No,” she choked out. “No, you didn’t check right.”

They asked about medications, about chemicals, about anything poisonous in the house.

Mom’s gaze darted to the nightstand, to the open jar with the fake “candy,” and her face drained of color.

Dad’s voice was hoarse. “What is that?” he asked.

Mom’s lips trembled. “It was… old,” she whispered. “I forgot… I forgot it was there.”

The paramedic’s expression tightened. “This is rodent poison,” he said, careful. “Where did he get it?”

Mom collapsed. “I killed him,” she sobbed, as if saying it might make it less true. “I killed my own child.”

They lifted my small body onto a stretcher. Dad followed like a man walking behind his own shadow. Mom stumbled after them, hair loose, hands reaching for me.

“Wait,” she cried. “Noah, baby, wait.”

At the top of the stairs, she slammed into the doorframe, hard. Blood opened on her forehead. She didn’t even flinch. She kept going, slipping on the steps, grabbing the railing, chasing the stretcher like it was the last train out of hell.

I hovered above them, watching Dad turn back to catch Mom before she fell, watching their hands clutch each other with desperation.

And then I saw it.

On the porch, our neighbor Mrs. Ramirez stood frozen, a small folded shirt in her hands. She’d been knitting things for the baby, and for me too, quietly, because she always slipped me snacks and called me “sweet boy” when Mom wasn’t listening.

When she saw the stretcher, her hand flew to her mouth.

“Oh, honey,” she whispered, and her eyes filled. “That shirt was for you. You didn’t even get to wear it.”

It was a little button-down, navy blue with tiny white stars.

If I’d worn it, I would’ve looked like myself.

Not a ghost. Not a replacement.

Just a boy.

6

At the hospital, everything smelled like disinfectant and old fear.

Dad stood in a hallway under fluorescent lights that turned his skin gray. He kept rubbing his cut palm like he could scrub time backward.

Mom sat on a plastic chair, rocking slightly, whispering my name over and over as if repeating it could stitch me back into the world.

“Noah,” she said. “Noah, Noah, Noah.”

A doctor came out, face soft but firm, and explained what they already knew. Explained that it had been days. Explained the poison. Explained that there was nothing to reverse because the ending had already happened.

Dad’s face crumpled. He made a sound that I’d never heard from him, not even at Lily’s funeral. It was grief stripped of pride, grief without the armor of “being the strong one.”

“I’m sorry,” he whispered, not to the doctor, but to the air. To me. “I’m so sorry.”

Later, when they went home, the house felt different.

Lily’s photos were still on the walls, but now they looked less like a shrine and more like witnesses.

Mom walked into my room and froze at the sight of the floral dresses in the closet. She sank to her knees and grabbed one, clutching it like it could explain why she’d done what she’d done.

“These killed him,” she sobbed. “I killed him.”

Dad, quiet as ever, opened my desk drawer and found the spiral notebook I kept hidden behind school worksheets.

My diary.

He found the key taped under the drawer, the way I’d done because I thought secrets could protect me. He unlocked it and flipped the pages with shaking hands.

The writing was messy, childish, slanted. But the words were clear enough to cut.

“Mom said I ruined Lily’s hair because mine got shorter.”

“Brent called me a monster today.”

“They poured water on me in the bathroom and laughed.”

“Dad made me cake. He said sorry. I wanted to tell him everything but I didn’t.”

“Mom says the new baby is Lily coming back. That means I can finally be free.”

Dad’s tears dropped onto the ink, blurring it.

He sat on my bed, diary in his lap, and it looked like the moment he finally understood something he’d been refusing to learn: silence doesn’t stop violence. It just gives it a room.

Mom stumbled in behind him, eyes red, face swollen from crying. She saw the diary and made a sound like her bones were breaking.

“I didn’t know,” she whispered.

Dad looked up, eyes burning. “You didn’t want to know,” he said, and his voice wasn’t cruel, just exhausted.

They sat there in my room, surrounded by the ghost of Lily and the ghost I’d become, and for the first time, they were forced to see me as separate from her.

Not Lily’s echo.

Not her stand-in.

Me.

7

The school found out, of course.

Small towns don’t keep tragedies quiet. They just change the way they say hello.

Ms. Carter came to the house with a social worker. She looked like she hadn’t slept. Her voice shook when she spoke.

“I tried calling,” she told Mom, and there was anger under the sadness. “He had bruises, Melissa. He had bruises that didn’t make sense for a kid who ‘falls a lot.’ We asked questions. He always covered for you.”

Mom didn’t defend herself. She couldn’t.

Dad went to the principal and demanded a meeting about the bullying. He forced apologies out of boys who suddenly looked small and terrified when faced with an adult’s grief.

Brent, the loud one, cried the hardest.

“I didn’t know,” he sobbed at the funeral, hands shoved into his pockets like he could hide his guilt. “I thought he was just… weird. I thought it was funny.”

There were too many flowers. Too many whispered apologies. Too many adults saying things like “If only we’d known” as if knowing would’ve automatically turned into doing.

Mom wore black and clutched a photo of me that she’d insisted on taking a year ago, when my hair was long and I was in Lily’s dress. In the picture, my smile was small and careful, like I was afraid of using up happiness.

Mrs. Ramirez brought the navy star shirt and placed it beside my coffin, smoothing it with trembling fingers.

“You deserved to wear this,” she whispered.

Dad placed Lily’s cloth bunny in with me. His hand lingered. His shoulders shook.

“I should’ve protected you,” he said, voice breaking. “I should’ve been your father, not your roommate.”

Mom leaned forward like she might crawl into the casket with me, like she might trade places.

“Noah,” she sobbed. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. Please forgive me.”

I hovered above them, watching their grief pour out now that it was too late to catch me.

And in the strangest way, I felt no satisfaction.

I felt tired.

I felt the way a candle feels after it’s burned down to nothing.

8

Grief doesn’t always punish people the way stories promise it will.

Sometimes it just changes the shape of their days until they hardly recognize their own lives.

After the funeral, Mom stayed in bed for weeks. The pregnancy complicated everything. The doctor called it “severe emotional distress,” as if the right phrase could make it clinical enough to handle.

Dad took leave from work and sat by her hospital bed when they admitted her for monitoring. He held her hand and stared at the ceiling, both of them trapped in a future they hadn’t earned.

Mom kept whispering my name.

“I’ll buy him shirts,” she said, half-delirious. “I’ll cut his hair short. I’ll let him be himself. Just bring him back.”

Dad’s voice was low. “We can’t bargain with the dead,” he said, and the words sounded like they scraped his throat. “We can only live with what we did.”

Sometimes, late at night, Mom would press her hand to her belly and cry.

“I wanted Lily back so badly,” she whispered. “I didn’t realize I was burying Noah while I did it.”

Outside the hospital window, the maple trees on Hawthorne Street turned bright and then began to shed, leaves falling like slow flames.

I hovered in that room sometimes, watching the monitors blink and listening to the soft hiss of oxygen in another patient’s room. Watching my parents become people who finally understood the cost of their choices.

And I kept circling the question that had haunted me even when I was alive.

Do parents like this deserve forgiveness?

I didn’t know.

Forgiveness felt like a word adults used to tidy up messes that were too big to clean.

What I did know was this: if hatred was a chain, it would keep me here forever.

And I didn’t want to stay in Hawthorne Street’s museum anymore.

9

When Mom was discharged, she did something I never expected.

She took down Lily’s photos.

Not angrily. Not like she was rejecting Lily. More like she finally understood Lily didn’t need an army of frames to exist.

She placed one picture of Lily, a small one, in a drawer.

Then she found the only photo Mrs. Ramirez had taken of me wearing a shirt. It was from my eighth birthday, a day Mom barely acknowledged, a day Mrs. Ramirez slipped me the star shirt and Dad let me wear it for an hour before Mom came home.

In the photo, I looked like a boy.

A real one.

My smile was wide, unguarded. Sunlight hit my face like it liked me.

Mom set that photo on my desk and wiped it clean every morning with trembling hands, like the ritual could erase the years.

She opened my closet and packed the floral dresses into boxes, sealing them up. She didn’t throw them away. She just moved them out of my room, like she was finally letting my space belong to me.

One day, she opened the balcony cabinet and pulled out the pink crib they’d bought for the baby girl.

She carried it into my room and set it by the window.

“This was supposed to be for Lily,” she whispered, fingers brushing the edge. “Then it became… a symbol of everything I did wrong. But I don’t want it hidden anymore. I want it to be… a promise.”

She laid a small blanket inside it. Not flowers. Dinosaurs. Bright green and clumsy, like Dad’s old pancakes.

Dad stood behind her, silent, eyes wet.

They started going to therapy. Mom sat in a circle of strangers and said out loud what she’d never admitted: that grief had turned her love into a weapon, and she’d pointed it at the wrong child.

Dad admitted his silence was a choice. That he’d been afraid of losing his wife more than he’d been afraid of losing his son.

At Roosevelt Elementary, Dad volunteered to speak at an assembly about bullying. He didn’t tell my story in detail. He didn’t make it a spectacle. But he stood in front of a room full of kids and said, voice steady:

“When you laugh at someone because they’re different, you don’t know what you’re adding to. You might be piling rocks on someone already drowning.”

Kids listened. Teachers cried quietly in the back.

It didn’t bring me back.

But it made the world a fraction less sharp for someone else.

10

Winter arrived like a lid closing.

Snow piled against the porch steps. The maple tree stood bare, black branches scratching the sky. Inside, Mom’s belly grew rounder, and every kick from the baby made her flinch with complicated emotion.

When the baby girl was born, Mom cried in a way that wasn’t just joy.

She held the newborn close, her face soft with love and bruised with memory.

“She looks like Lily,” she whispered, then swallowed. “And she looks like Noah too.”

Dad stood beside the hospital bed and said, voice trembling, “We can’t make her carry anyone’s ghost.”

Mom nodded, tears spilling. “No,” she agreed. “Never again.”

They named the baby Nora.

Not Lily. Not a resurrection. Not a replacement.

Nora, a name that sounded like a new beginning.

They gave her a middle name too. Rose, after Mrs. Ramirez, who’d been kinder to me than my own mother had been able to.

Back at home, Mom carried Nora into my room, now cleaned and rearranged, my photo in the star shirt on the desk. The pink crib sat by the window, dinosaur blanket folded neatly.

Mom rocked Nora gently and whispered, “Your brother should be here. And he’s not. And that’s because I forgot how to be his mother.”

Dad stood in the doorway, hands in his pockets, eyes fixed on my desk like he expected me to walk in and ask for dinner.

Nora slept with her tiny fist curled.

Mom’s voice softened. “When she grows up,” she said, “we’ll tell her the truth. Not as a curse. As a lesson.”

Dad nodded. “We’ll tell her Noah existed,” he said. “As Noah.”

11

When Nora learned to crawl, she crawled straight into the pink crib like she’d claimed it.

When she learned to walk, she toddled into my room and patted the desk where my photo sat, babbling sounds that weren’t words yet.

Mom watched her with tears in her eyes, smiling the way she used to smile before grief hollowed her out.

One spring day, when Nora was old enough to form real words, Mom carried her to the cemetery.

The grass was bright. The air smelled like thawed earth and new leaves. The world looked like it was trying again.

Mom knelt by my headstone and traced my name with her fingertips.

Noah Daniel Hart.

No flowers carved. No lie carved. Just my name.

She pointed at the stone and said softly, “Nora, sweetheart. That’s your big brother.”

Nora stared with wide eyes, then lifted her small hand and touched the engraved letters like they were braille.

“Bubba,” she said, voice unsure.

Mom’s breath hitched. “Yes,” she whispered. “Your brother.”

Nora leaned closer, serious as a tiny judge, and said, loud and clear, “Hi, Bubba.”

Mom broke then, crying into Nora’s hair. Dad crouched beside them, one hand on Mom’s shoulder, one hand resting against the stone like he was trying to hold onto something solid.

In the breeze, the leaves on the maple trees above the cemetery fluttered. Sunlight flickered across the grass, bright and gentle.

I hovered nearby, watching them.

I didn’t feel pulled back.

I felt… lighter.

Because whatever my parents deserved, they were finally doing the one thing I’d needed most when I was alive.

They were seeing me.

Not too late for them to feel it.

Not in time for me to benefit.

But real.

And maybe that was the closest thing to forgiveness I could offer.

Not absolution.

Not a clean slate.

Just the decision not to drag their worst selves into my afterlife and chain myself to it.

In the end, forgiveness wasn’t a gift I handed them like a prize. It was a door I opened for myself, so I could leave.

“You don’t get to rewrite what you did,” I thought as the wind moved through the trees, “but you can choose what you do next.”

And as Nora’s small voice echoed against my name, I let the last thread holding me to Hawthorne Street finally snap, soft as a lullaby fading into morning.

I drifted upward, past the cemetery gates, past the quiet streets, past the maple tree that had watched every season of my short life.

This time, I didn’t look back with anger.

I looked back with the tired tenderness of someone who finally understood: love can be real and still be wrong, grief can be honest and still be cruel, and some apologies arrive only when there’s no one left to receive them.

If there is another life, I hope I get to be a child who is allowed to be himself from the very beginning.

I hope the world treats all children with gentleness.

And I hope my sister, wherever she is, is warm.

THE END

News

HER FATHER MARRIED HER TO A BEGGAR BECAUSE SHE WAS BORN BLIND AND THIS HAPPENED

Zainab had never seen the world, but she could feel its cruelty with every breath she took. She was born…

In 1979, He Adopted Nine Black Baby Girls No One Wanted — What They Became 46 Years Later Will Leave You Speechless

In 1979, He Adopted Nine Black Baby Girls No One Wanted — What They Became 46 Years Later Will Leave…

They said no maid survived a day with the billionaire’s triplets—not one. The mansion of Ethan Carter, oil magnate and one of the richest men in Lagos, was as beautiful as a palace

They said пo maid sυrvived a day with the billioпaire’s triplets—пot oпe. The maпsioп of Ethaп Carter, oil magпate aпd oпe…

An Obese Girl Was Given to a Poor Farmer as “Punishment”—She Didn’t Know He Owned Thousands of…

The dust swirled around the worn wheels of the old Chevrolet truck as it pulled up to the modest farmhouse…

Man Abandoned Woman with Five Bla:ck Children — 30 Years Later the Truth Sh0:cked Everyone

The first sound I ever heard my children make was not one cry, but five, layered on top of each…

THE LEGACY GALA – He Left Her Because She “Couldn’t Give Him an Heir”… Then 20 Years Later

Closure has a scent too. It smells like the moment you finally turn off a light you’ve left on for…

End of content

No more pages to load